A miners' cottage at Moonta Mines (now a restored

dwelling and a National Trust building) which is typical of the cottage

the Quintrell family lived in from the 1860s until its demolition in

1970.

A transcription of the memoirs of my paternal

grandfather

Stephen William Quintrell (1871-1960).

Transcription notes:

There are two different versions and a brief fragment

covering slightly different episodes. With minor exceptions (shown in

square brackets) the following is a direct transcription of Stephen

William's handwritten memoir. Place names and personal names are

transcribed directly.

Biographical note:

Stephen William Quintrell was the fifth of

thirteen children born to Stephen senior and

Mary Ann Datson. Stephen snr (aged 8 years) arrived at Port Adelaide on 11

Sept 1858 on the 'General Hewett' with his parents John and Mary (nee

Toy). He was the fourth of five children.

Mary Ann Datson's parents (Hugh and Jane) arrived at Port Adelaide on

the 'Aboukir' on 4 Sept 1847. Mary Ann would have been 3 years old, having

been born in Cornwall in 1844. Stephen snr and Mary Ann married at the

Wesleyan chapel, Moonta SA on 2 Sep 1865.

'Version 1'

I was born at Moonta Mines on the 5th of

July 1871. My father was born at Liscard, Cornwall, and mother at Redruth,

Penzance, England so, by that, as a friend said to me once when asking

what Nationality I was, parents both from Cornwall and myself Moonta

Mines, that I was a pure Cornishman. I went to school at an early age to

the Mines Model School and was one of the first scholars when it opened

under Headmaster Dr W. G. Torr. Moonta Mines at that period was at its

best. My father was a Surveyor Draughtsman under Mr H R Hancock. We

shifted to Adelaide in 1881 and I went to the Tynte St [School] under Mr

Gill. In 1885, I entered the Government Service in the Water Conservation

Department under J. W. Jones, Conservator. While there I worked in the

office in the new Government Building, Victoria Square. After 18 months at

2/6, and never cared for indoor work, I went into the field with the

Surveyor, and my first job, I was sent away north to Yadlamalka, north

from Port Augusta under W. W. Mills, surveying along the west side of the

Flinders Range towards Warrakimbo, Marachowie and Mt Eyre which was a

deserted township used in the old (illegible).

On completion there, we came back and travelled through

the Pichi Ritchi Pass to the east side of the range to Quorn, then on to

the Te Tee Va Springs at the mouth of Depot Ck, where we made our camp,

then worked along the range towards Mt Ragless and Ardenvale. Depot Creek

Gorge runs through the Range from the east to the west side. While there I

climbed to the top of Mt Arden and repaired the Trig. On top of Mt Arden

you get a glorious view. Looking towards the west you can see the Tent

Hills onning(?), Lake Torrens to the south, Mt Brown to the north across

the saltbush plains as far as Mt Desolation, and to the east Mt Ragless

and the Willochra Plains. It's worth the climb for the view.

On completion of our work there, we came back and

travelled north past Hawker and Hooking to the Moralina Creek at the mouth

of Wilpena Pound. One thing I remember while at the Depot Creek camp: we

went to a party at Ardenvale township—nearly all German settlers and I

had my first experience of a German bed, a feather bed and (illegible).

From Moralina we worked along the old survey line and then on to

Parachilna, and pitched our camp at the well at the mouth of the Oratunga

Gorge, and through the pass to Blinman. At Parachilna, the hotel was kept

by Bill Darmody, and the Blinman Hotel by Remington Barnes of Shootover

fame—Adelaide Birthday cup 1888.

We worked along the Breakfastime to Wilpena and

surroundings. At the Oratunga, I met up with Bob Caldwell afterwards. The

next time I met Bob was when he was Resident Engineer for the Railways.

After finishing our work there, we called to Adelaide camp and horses. We

came back through Hawker, Craddock, Hanawerie(?), Terrowie, Burra, Kapunda

to the Survey yards, Thebarton and disbanded. My camp mates were Surveyor

W. W. Mills; Jack Fotheringham and myself, chainmen; Sam Moore, axeman; H

Edeina (?), teamster; and Newt Gregory, cook.

1885 to 1888.

My next job was with was with Surveyor J. S. Furner,

surveying and leveling from Woodside through Lobethal, Cudlee Creek and

Millbrook, also (illegible). Then I was at B. Hill until the 1892

Strike started and then we were all scattered to different stations. I was

lucky, being sent to the SouthEast, and was not sorry as the Typhoid Fever

was prevalent. Silverton and B Hill hospitals were full.

South East: I started in the South East at Naracoorte

and it was a great contrast to the dry north. It was winter time and

[with] the rains and the water laying about, it seemed a different

countree (sic). Superintendent was C. F. Girback and afterwards, W.

Miller; leading fitters Curly Howbel(?), Tom Kingdon; Henry Gens was

apprentice—afterwards Mine Host of Gens Hotel, Mt Gambier; Steve

Staunton, blacksmith; H. S. Hamilton; clerk and P. Prince. Afterwards I

was sent to Bordertown where I had the misfortune, on turning the engine

on the turntable, to get my left foot crushed and opened badly. Bob

Stephenson was the driver and I was off for several months. On resuming

work at Naracoorte on the roads to Kingston, Mt Gambier to Bordertown, 3rd

rail for narrow gauge ... (illegible) ... to Bordertown and Mt Gambier

and Beachport with different enginemen; Jack Eager, W Cornell, P Crafter,

Jack Smith, Amby (?) Snell, Jim Mackie, Amos Clark.

In 1894, I got married to my dear wife, Edith Long in

the Wesleyan Church by the Nara Creek, and was transferred to Kingston to

fire for Charlie Hall, Kingston and Naracoorte line. I was 7 years at

Kingston with Charlie and I enjoyed every day of it there. Most of the

latter years we were working 3 days a week, except in the wool season.

Sport, cricket and football, of which I was the captain, and foot racing.

There was plenty of fast runners, good Sheffield runners in J McKinnon,

Pinkerton's son Martin, Tapfield of Black Ford, Charley Threadgold of

Murray Bend. While I was there I had the knowledge of what a real

earthquake was like, an experience of which I'll never forget. It was

supposed to be a Marine Volcano at sea off Cape Jaffa erupting, and for

several months, the shakes continued. I had to go 3 days a week on a trip

up to Naracoorte and you could hear the rumble of the shakes coming from

Cape Jaffa and feel the shake passing the old galvanised shed, and the

iron girders shaking and rattling and rumbling north towards Murrabinna

way, making you feel very queer until you got used to it. In 1894 Roy was

born, during the earthquake season.

After years at Kingston, I got rated as a fireman at

eight shillings per day, and while there Ralph was born in 1898 and Norman

in 1902. While there I had my first trip in charge of an engine—

Naracoorte and Wolsley and back, Bert Rumball as fireman. After a time, I

was transferred to Mt Gambier, and this time it was disastrous for

Depression set in and 18 enginemen and 18 firemen were reduced in rank. I

was one of the unlucky ones. I was reduced from 8 shillings a day to 6/6

but the irony of it was, although I was reduced in status, I was still

doing the same work, but at reduced pay and it rankled. [From] Mt Gambier

we ran trains to Beachport and Wolsley. While at Mt Gambier, Edie and I

saw the opening of the tower at the top of the Mount overlooking the

Valley Lake—a good view from the top of the mount looking south to Port

McDonnell, where Edie was born, and Mt Shank, another extinct volcano. We

lived at Whel St, Mt Gambier. Mt Gambier is a very pretty place, but wet

in the winter, but the water does not lay about owing to the hollow

ground. Gambier [people] are proud of their lakes—Blue Lake, Leg of

Mutton Lake and Valley Lake. During the wet season, with Roy with the

croup and Norman also, Mt Gambier weather was detrimental to the health of

Norman's health (sic). The doctor advised us it [was] best to go north to

a drier climate, so I got a transfer to Pt Pirie. There I started on the

BHP Shunter with Shunt Engineman A. H. Bevell. I was not long in Pirie

before I got reinstated as a fireman at 9 shillings a day. Pirie did not

seem an advantage for a while. There is no beauty about it but ...

(illegible) ... plenty of life and splendid people and the friends we

made there remained friends, although, sad to say, the only ones remaining

is dear Mrs Daly and family.

We had a bad start when we arrived in Pt Pirie as

Norman took very ill and it was tough ... (illegible)... with him we

had to keep him in cotton wool most of the time he was ill. While at

Pirie, my brothers Clarrie, Jack and Dick came there to work, and stopped

with us. At Pirie there was a fine lot of fellows to work with; most of

them are dead now—mates on the road. I fired for Jack Coulson, J.B.

Shrives, Alf Holthouse, W Alderson, Drivers; Tommy Hart(?), C. Job, Tom

Brennan, Jack McFarlane, Jack Mackie and a lot of others. While at Pt

Pirie I was borrowed by the Marine Board for a time to relieve their

engineer, taking charge of their engines to work on the long jetty. They

had 2 small engines, a SAR Narrow Gauge V, and a Kitson pump engine. I was

sent as I had experience [with] a Tange pump engine on the diamond

drilling. My work was to load the Celtic Queen sailing ship with wheat.

There was one mishap. I started with the V as I thought she could pull the

heaviest load. I worked the V for one day and on lighting her after

getting steam, I was filling her tank with water when the corner of the

firebox blew out. I was not long getting the fire out. The engine shed was

on the jetty. I sent word to Pt Pirie about the mishap, and Mr Hill,

Superintendent came. He took the coal pick and went underneath. He found

that he could punch holes all around the foundation of the firebox as she

was eaten all round. He told the Harbourmaster they did send a man over a

man (sic) to work taking such risk and without an examination.

Pt Pirie is a lively place. When I first [got there] I

got out at Pirie South and walked down Ellen St. The trains—passenger

and shunt—ran the length [of the main street]. The mineral trains from

Broken Hill ran down the street to the smelting works, pushing the trucks

ahead, with a porter ringing a bell. When a Yankee engine No 48 ran the

ore up to a bin and the refinery, I don't think any city anywhere else is

like that. Also, Ellen St [has] one side shops and pubs and the other

wharf, ships, big timber stacks. The train left Pirie every day for

Petersburg, Jamestown, and Gladstone to Hamley Bridge.

I was in one accident while we were there, when coming

into Petersburg Station and the signals showing 'all clear', we crashed

into 'Big Ben', a T Class engine which had stopped at the points

controlling the main line and the railway yards line. I was firing a Y

class engine of a mixed train with my mate Alf Holthouse. We caught Big

Ben in the centre. Our engine, a Beyer and Plack English-built (and what

splendid iron and steel was put into her!), she put the big engine over on

her side and cut her rods cylinder—cut them off like cutting through

cheese—and our engine fell over and buckled up. I did not remember much

as I was unconscious, and the tender and coal covered me until they could

release me. I suffered with bruised ribs and body, and shock, and [was]

sent back to Pirie to be doctored by Dr Hampton-Carr. I was off for a

while, and on my return to work I started with J Coulson on a Race Train

for Balaklava, and started when Coulson sang out 'Look out!'. They had the

points set for the loco and we crashed into the dead engines in the loco

shed. I got another shock and I left the engine and walked home.

In 1911, I was made a 3rd class fireman and

was transferred to Petersburg, and started once more on the Cockburn

roads. I was not long at Petersburg before I got another accident. I ran a

Class Y, just off the stocks, for a trial trip to Belalie and was on the

pit at Loco when the Chargeman, Alf Stevens, ran out to tell me 10 big

trucks had got away from the shunting yard and were running down the grade

to the Loco. I was alone on the engine. I ran with the engine to meet them

so to prevent them running into the running sheds there were fitters and

cleaners underneath them. I saw them coming fast and reversed to run with

them and then reversed until they were just on me, and started steaming

against the funnel. I opened the regulator and started steaming against

them until we reached the running shed. We gave the engine in the shed a

broken ... (illegible) ... but no one got hurt. Damage—a few trucks.

Just before this happened, some trucks broke away from

a train at Natabibbi, and the guard jumped into a big truck and put the

hand brake on and stopped them. He got a bonus of 50 pounds. S Kidman the

big cattleman happened to be riding passenger with him. J C Sharpe, the

foreman, came to me and said "Well, Mr Man, Jimmy Keane got 50 pounds the

other day for his job of stopping 3 trucks, so I expect a bottle of

Champagne when you get yours. I said, "Righto!". A few days [later] he

called me into the office. "here's a letter for you from the

Commissioner's office. They said no champagne for your action, although

it's a very nice compliment to you." I got on parchment telling me that

the action I took to stop the running truck prevented great damage to the

engine and the engines standing in the shed, and the injuries for them

working was extremely praiseworthy, and would be put on my record. No 50

quid. I have the commendation still, but I'd sooner have the 50 quid!

Worked on the Cockburn from 1911 to 1916. In 1914, the

World War started. By the way, we were not long at Pt Pirie, when Edie

remarked "I would not be surprised to see Clarrie come here", and it was

not long before Clarrie tossed up his job and came. Quiet old stick,

Clarrie. The only remark he made [was], "I'm here, Edie." He remained and

took a job in the Loco as storeman. Clarrie could not keep away from the

boys re the War. In 1915, Roy enlisted in the 9th Light Horse

as a trumpeter and sailed. Clarrie said that someone ought to go to look

after him, and he enlisted. He tried to get into the Light horse but

failed to pass so he went into the Infantry. When Clarrie went, Jack and

Dick enlisted. Roy came back, but Clarrie, Jack and Dick got killed within

a fortnight, Clarrie and Dick in France and Jack at sea. (See the stories

of Stephen's brothers at JAQuintrell and WW1,

Richard H Quintrell and Clarence H Quintrell).

The Cockburn road was the best I worked, although it

was the hardest. You had your own engine and your own mate. It was along

run and long hours. When you left Petersburg, you did not know what would

happen. Dust storms, ants, grasshoppers, grubs, washaways, thunder storms

—a lot of things happened on the 45 mile run. Ants were a curse on

Narrabibbi. When they were travelling they would strike the railway lines

and then run along them, causing the engine to slip. Also the stench would

make you want to vomit. Grasshoppers were nearly as bad. They would come

in millions and in the cuttings pulled you up. Grubs migrating were nearly

as bad as ants, but you got rid of them quickly. McDonald's Hill was the

worst place for grubs. They were all going one way, and they go as

suddenly as they came. Where they end up, goodness knows. Storms and

washaways would come up suddenly. I remember one. I left Cockburn after

the BH Express left on getting to Marreaba. I saw the express standing

there and the Station Master came to me and told me to uncouple my engine,

and run to the top of Oulina Bar(?) as there was a washaway right at the

top. When I got there the gang there was repairing the road, so I had to

run the big T Class engine over to see if it could stand the express

crossing it. It appears there was a cloudburst and the ballast was washed

away from the sleepers at the top of the hill. I left Olary in a big

storm. It was a beauty—thunder and lightning and rain. There is a big

hill between Olary and Oulina—a lot of iron ore chiefly—and the hill

is scarred with it. The water was coming down in waves. The culverts were

shallow. I got through but it was days before any of the others.

At that time, all along the road, you passed people

going along tramping it for Broken Hill, or 'jumping the rattler' in the

open trucks. We did not take nay notice of them. Ben Cotton, signalman at

Oatalpa saw 5 or 6 one day riding and ordered them out. I told him that he

would be sorry, and he told me afterwards that he was, for they killed

some of his goats to eat, and he had to feed them. He never put any

"rattlers" off after that. Cockburn was a home from home. I slept in the

old Barracks, and the new Barracks were splendid and comfortable. The

bedrooms [were in] a two-story building with rooms both sides. Lavatories

and washrooms away from the bedrooms and Dining Room. A big roomy place

off the Dining Room; kitchen with two big ranges, and two sitting rooms,

one for the smokers and the other for Nons.

I was on the Cockburn Road from 1911 to 1916. There

were fine fellows on that were always willing to help one another, and

fine enginemen, willing to learn their job for that road. If you had a

breakdown, you had to manage, and they would always stop and help, for you

could not send for a fitter, and many a time you would come to your

journey's end working with one side. We had the advantage of having a

splendid teacher in Engineman Harry Pearce on Engine and the Westinghouse

Brake. He would repeat and show you over and over again until you

satisfied him. Very patient. No wonder the Cockburn men were so efficient.

When you came up for your certificate on both Engine and Westinghouse and

train handling, very seldom anyone failed. Also all road men were

certificate Ambulance men, and the men were true mates. Men like Davey

Collier, Harry Pearce, Tom Angrave, Jack Russell, Harry Liston, Nazo

Trueman, Charlie Vine, Billy Woods, Tom Clarkson, Herman Yon, Bill

Harding, Jim Mackie, and others, All good men and good comrades.

While at Petersburg, my father died. I met him once

when he was Inspector of Mines at Marine Hill, and he rode with me to Port

Burge, and stopped with us for a day. He died soon after.

1916 ended my narrow gauge work. I had experience with

all classes of engine, both firing and driving on the Narrow Gauge from

the smallest to the biggest. Engines Y Class, W, WX, and U, Yankee, Tangie,

Z Express, Big Wheels, K Shunting, Petersburg T Class.

1916—1936.

In 1919, myself and George Platten were transferred to

Adelaide. I learnt the suburban line with Engineman Stephens, and the

South road with Engineman Fred Linfoot, and Victor Harbor line with C

Everall. From then on I worked South road to Tailem Bend and Karoonda

Murraylands line, Mt Pleasant, and Sedan, and North lines. Worked on North

as far as Gawler—all suburban lines. Adelaide on Glenelg line, round

trips to Victoria Sq and back. Henley Beach and Semaphore and Outer

Harbour and Northfield. On Glenelg line we worked P Class engine, standing

coal for the trip in the small cab, and from South Tce to Victoria Sq

ring. Our Sundays away from home were spent at Murray Bridge, Tailem Bend,

Mt Pleasant. I was not long at Mile End before I was sent—knowing all

the north—relieving for 6 weeks at Petersburg, Pirie, Pt Augusta and

Quorn. At Mile End we had several classes of engine to work—R, RX, TX,

500, Mountain Type, 600 Pacific, 700 Mikados and P. For the next 20 years

I worked all sorts of trains—Freight and Passenger, Express,

Commissioner, Royal.

The most expressie(?) train was the first hospital

train from Murray Bridge to Adelaide with the first of the wounded

soldiers from the First World War. I was appointed the leading engine with

Tom Trueman the assisting engine. My engine was 217 and both engines and

tenders were decorated by the women of Murray Bridge and Cleaner(?) with

coloured garlands from the coppertop to Dome to the Cab and all along th4e

side, and the leading engine (217) with a big shield in the front of the

smoke box. We had to slow down to 10 miles per hour through all the

stations and I'll never forget us crawling into Adelaide Station and the

crowded platforms. Ralph was married in 19and Norman in 1928.

Another event was in 1929 when I crashed with the

East-West Express on Warla Hill, halfway to Callington, owing to the

bridge washing away owing to a terrific thunderstorm. The water came from

between two hills, washing the ballast away, leaving only the rails and

sleepers standing. I have been in and seen storms before but never quite

like that one. The Mountain 508—the 'Sir Lancelot Stirling'—rolled

over to the right and, striking the stone supports of the bridge, fell

over to the right and cantered over, swinging the big tender across the

line. The rail came right through the cab just missing my mate Alick

Rowberry and the coaches of the train, breaking the couplings and tore the

end of them. The corridors being on that side of the train, shedding

wheels off into the creek—luckily for the passengers there was no one in

the corridors—until it came to the sleeping coaches and the brake. The

guard of the train was Fred Gherkins. The first sleeper coach—the

'Baderloo'—fell over afterwards. We got the people out and she fell over

afterwards. There were water all round the engine. There was a few

casualties, none seriously, a few bruises and shock, and as a whole, they

were a splendid lot of passengers. They had no complaints but a lot of

thanks. A peculiar thing of this [was that] in the last coach was my old

mate Alf Holthouse was riding in the coach next to the brake van. [He was]

coming to Adelaide, being a sick man. He was my mate in the accident at

Petersburg with Big Bend, and the guards did not realise until afterwards

that there had been an accident. There was an inquiry over the affair, but

neither Alick or myself was asked to attend. We were there for some hours

before the relief train from Adelaide backed up to take the passengers to

the city, with myself and Alick in the brake van, which stopped at Mile

End Goods to alight, as they did not want us to go into Adelaide. I got

home and found the News Photo man and Victoria Reynolds waiting for me,

and Edie astonished for they [had] told her that I would not be home until

later, as I was working a later train—very considerate of them—and so

she should not worry.

The SouthEast passenger [train] came from Murray Bridge

and stopped at the back of our train—W Shultz and Fireman Haines the

train men—with the Superintendent from Murray Bridge. After the water

dropped down, I sent my mate and he got over and went to Callington to

report while there. Some men from a Highways camp and brought two big

billy cans filled with coffee, which was appreciated. A peculiar thing

about it—that morning before we booked, we were having breakfast with

the SouthEast crew—W Shultz and B Haines—[and] I said I had a funny

dream. I dreamt that we were working a train and fell into a great pool of

water, and the engine sank to the bottom. [We] were sitting on the bank

when the Head came up and asked how they were going to get the engine up.

I said, "That's easy. Get down and empty the boiler and pump her up with

air and she will float up!" The Fireman (Haines) came up off the SouthEast

train and said to me, "What about your dream last night? If that was not a

premonition!" They had me booked next day—that was a Saturday—but my

son Ralph objected, so they crossed me out, but sent me out on the

Melbourne Express on the Sunday. That was the last trip I had with Alick

as he took ill with (illegible) and went off the road into the

sheds.

The road from Nairne to Balyarta was always a hoodoo to

me, as also affairs that went wrong always happened to that section.

Running down from Nairne to Balyarta with a goods train composed of trucks

with a few in front equipped with air and the rest no air, I steadied them

down and [had] just released the brake when, coming out of a curve, there

was the maintenance gang going to work on a trolley. We tipped them off

the road. When I could pull up I went back to see if anyone was injured. I

met the boss who told me that everything was alright, only the old boiler

they used to have to make their tea was the only thing broken. On reaching

Balyarta, I went to the front of the engine and (illegible) to see if

[there was] any damage. I found two oilskins and a billy of tea, with tea

in it, riding on the bogie axis.

Another time, working a Mikado, I stopped at the

Station Yard to cross a train when one of the big tubes in the firebox

burst and left me stranded. The hoodoo continued. On the express one day—

the Railways Commissioner on board—I went through Callington with a

minute to spare. I let her run down to pick her up for the climb to Warla,

when she came to a stop. No power! The regulator [had] come uncoupled in

the Dome, so no steam could pass through the steam and cylinders. Mr

Anderson came up. He said Mr Webb said, 'Well, the driver has given us a

nice ride so far, and now he has stopped so we may drink our coffee, you

better see what's the matter.' He asked me the reason and also what I was

going to do. I told him my mate had gone back to Callington and wired for

a Mountain Type or a boostered Mikado. We waited for some time until a

Pacific engine came down. I told him, it's of no use as her load to pull

was 350 tons, and she was of no use as I had 426 tons in coaches and the

tender [another] 220 tons, so she could never pull up the grade to Warla.

He asked what to do, and I told him the Pacific could ... (illegible) ...

only pull the dead 500, and told him to wire a heavy engine to get the

train. When the Pacific came, we uncouple from the train and [it] pulled

us up to Warla. Then he told me to come with him to the telephone box and

he not slate them (?). I heard him say, "You, in your wisdom, thought you

knew more than the driver, a practical engineman. Now here we are at Warla

with the engine. Mr Webb and the Commissioner are still down the bank, and

a serious delay again!" He asked me what should be done. I told him, here

we are with the dead engine and the Pacific engineman J Temby, and the

engine and crew of the Pacific is to work the express from Tailem Bend

across the desert to Serviceton. He could tow me to Murray Bridge and take

water there, and take her the remainder of the trip. The 500 class, when

she came, could go down and pick up the Express and leave me at Murray

Bridge to be picked up later. He instructed them to do so.

The hoodoo continued. Sometime afterwards, also on the

Express, the same thing happened on going through Balyarta. When I started

to pick her up for the rise to Callington the same thing happened, but

when she stopped I let her run into the Balyarta yard and telephoned Mile

End. There happened to be a Mountain Type engine at Aldgate, with

engineman Len Taylor there, so they sent her down to pick me up. After the

two mishaps they put a collar over the joints to prevent it [happening

again]. While waiting at Balyarta, they had the Dining Car on, and they

came to the engine with tea and fish and chips. I told the waiter it was

very kind of him, and he said, "That's alright. They are going to uncouple

the Dining Car at Tailem Bend, and there's a dance on there, so that will

suit us."

Another one that I can recollect was on the suburban

[line]. I left Henley Beach on the morning train and, running into

Marlborough St [Station?], I saw a young baby, about 2 years old, playing

in the ballast. I did a quick stop with air and reversing steam. This did

some damage to the draw gear of the (illegible) and shook up the

passengers. I just stopped and I could just see the child over the

buffers. I got down and took the child to the lady caretaker. [the next

page/s are missing]. .....

I had 12 hours to finish my time, so they put me on the

10.25 am to Bridgewater with the Centenary Train—train and coaches green

and gold—and on Tuesday, with four hours to make, they sent me on the

'Dolly Grey' to Adelaide. Put me on one of the sidings, and left me there

with nothing to do until 12 noon, and then sent me to Loco. I had a proper

Railwayman's sendoff. I started for Mile End, and we pulled up at the Goal

curvey(?), when the signalman, an old mate, Arch Templer, and the carriage

shunters said "Good-bye". At Mile End Cabin, they closed the gates on me,

and signalmen Schoff and W Virgin said their good-bye. On arrival at the

sheds, the foreman Talbot came to me on the pit and I asked to send

someone to stable the engine. He said, "No. Examine the engine and book

your repairs, and make the engineman's sheet out, and then come with me."

He took me to the big Dining Room. It was lunch hour, and there were

speeches from the fitters. One said that some enginemen, when their engine

is not going too well, report their steam chest valves for examination too

often, but when engineman [Quintrell] reported the valves, I never found

him wrong. They presented me with a beautiful gold watch, "Star Dennison",

and pipe and accessories. The Commissioner of Railways said it was a

mistake, this age of men. "Good men reaching the age limit like engineman

Quintrell, who is good enough for another 5 years, but it is the law, and

even I have to retire when I reach it." While there a telegram came from

Brisbane from an old Cockburn road man, Jimmy Steadman. It said "Goodbye

Steve—one of the old brigade". So that was the end of my working days

and, with the words of Adam Lindsay Gordon's 'The Sick Stockrider', I can

say

I've had my share of pastime, and done my share of

toil,

And life is short—the longest life a span;

I care not now to tarry for the corn or for the

oil,

Or for the wine that maketh glad the heart of man.

For good undone, and gifts misspent, and

resolutions vain,

'Tis somewhat late to trouble. This I know

I should live the same life over, if I had to live

it again;

And the chances are I go where most men go.

1936

I started off thinking of the Good Times ahead of

me, but it was not to be for my dear Edie started ailing, and lingered for

2 years' suffering. There was hope for her getting better, but she died at

Calvary Hospital and was buried on my birthday. [This] was the saddest

time of my life, after being married for 42 years. She was buried with her

mother in West Terrace Cemetery. My home was broken up, and I went to live

at Walsall St, Kensington Park for 12 months.

In 1939, I went to Melbourne and stopped at Kew with

Edie's sister Topsy for several months. When Roy went to live in Ruthven

Mansions, I migrated to Kingston in the South East from 1939 to 1944 and

boarded with the Hayes family at the Coffee(?). World War Two started in

1939 and Norman went into the Air Force, Roy in the Military at Keswick

Barracks, and myself spotting for aircraft at Kingston. The Hayes family

made me feel at home. They were a lovely family and I was quite happy

there, for I seemed to be nearer Edie, as the happiest time I ever spent

was there.

Kingston is not what you would call a pretty place. It

is a place where time seems to stand still. I could wander about looking

backward to the past. There was the house that Roy was born in, a fairly

comfortable place named 'Kulkyne', owned by the Abbotts who kept the

store. The hotels [were[ the Royal Mail, kept by W Pinches; the Crown,

kept by Arthur, Doris and G Wilson; the Kingston Arms, kept by T Newson

and J Collins (now Hayes Coffee Place). [There was] the old engine shed

where I spent many lonely nights, and the fishing boats—Volunteer,

Mavis, Royal, Petrel, Jennifer, Annie, ... (illegible). I had plenty

of enjoyment going out in the fishing boats for crays with Walter Blackler

in the motor dinghy off the point for picking, and fishing off the jetty

for mullet, yellowtail, silver whiting, flathead and garfish at Kingston

or Port Caroline on Lacepede Bay. [The bay] is very weedy and a good

feeding ground for fish. Plenty of sharks—white pointers, grey nurse,

hammerhead, whip, and sweet william—I have seen there as at Port

Caroline the whole sweep of the Southern Ocean right from the Antarctic

rolls in there. I have seen seals [and] sea lions [and] also albatross

come in there. They were good chaps the fishermen of Lacepede Bay—Jimmy

Forbes and his brother Bill of the 'Mavis'; the Blackler brothers of the

'Petrel'; Wag Winter, Dallisons of the 'Annie'. Ned Barber [also] sailed

out with them.

While living with the Hayes, every first Tuesday in the

month, I used to go with Walter Smith skin buying in his big lorry. He

bought skins in a big way and always carried with him big money. He also

wanted a companion he could trust. We would start from Kingston and visit

all the rabbit camps and stations from Kingston and the Coorong, going

through to White Hut, Dalkeith, then across to Tillies Swamp (?), Tatiara,

Salt Creek, Policeman's Point, Woods' Well, McGrath Flat to Meningie the

first day, stopping at Meningie at the hotel, Walter paying all the

expenses. The next day to the Tatiara Station, Ashfield, Potalick, across

the punt to the Point McLeay Mission Station, Narung to Campbell House and

back to Meningie. The next day we did the township and loaded up and left

Meningie after midnight, and through the Coorong back to Kingston.

I did plenty of fishing off the jetty, and one day I

caught a lovely fish, and looked through Bill Hagget's Fishery Book. It

was a Sea Robin and very rare. I used to spend off weeks at Cape Jaffa

with Jim and Bill Forbes going out to the reefs, cray fishing around the

rocks. I liked it very much down there—a fine hut and plenty of company.

There were five boats there—Forbes, Len Goldsmith, Jeff Harrington,

Frank Winter, Vin and Yacka Backler—and plenty of snakes!. A lot of

people come to Cape Jaffa for the fishing, people like the Tolleys of

whisky fame, Archie Holmes and Ben Matson and his two son-in-laws—not

forgetting Blackie and Dave Pannell. We used to play Nap of a night among

ourselves; we had two beer mugs full of pennies.

We fed well there. I used to love them smoked. When we

pulled up the pots out on the reef by the lighthouse, you often found fish

in them and octopus. We had a bar across the top of the chimney and we

used to hang the fish there with a barrow load of sheoak and current (?)

wood chips and smoke them a nice golden brown, leaving them there all

night, and for breakfast, in the frying pan with sea water, they were

delicious.

I also took on wattle bark stripping. The agents gave

five pounds ten shillings a ton—a big price—so old Harry Cooper and I

took it. Harry was a grand old chap; he was 75 and I was 72, two quite

young fellows! Harry had good bush implements—a fine bush tent and

flies, and all the tools—so we went to Noolook, made our camp in a big

SiAli (?) bush. These SiAli trees grow immense. One tree will start, and

then as time goes on it throws out branches, and when they touch the

ground they root like a Banyard tree. The wattles grow very thick around

Wangolina, and we made good money. We could get a ton a week, and it was a

great experience for me. We had a cosy camp, and Mr Hayes would send out

by the mailman to Robe plenty of food, and come out now and then to bring

us in on Saturdays. I thoroughly enjoyed being out there: you could sleep

well and eat well. Harry was a great old bushman and good company. It was

great out there. In the morning you would wake up by the birds: first one

would start, then another, and all the birds in the wattles would begin

their morning song. And then at evening time, the birds would be giving

you a grand chorus before going to roost. First the wattle birds would

begin, then the rest would join in. The last one to chime in, just as

darkness et in [was] the ugly old Mopoke, with his dolorous "Mo-poke".

The wattle company is a great feeding ground for birds:

wattle birds, paratoos, ringnecks, green linnet, black cockatoos, white

cockatoos, king parrots, grass parrots, redcaps, rosellas, bronze wing

pigeons, the ugly old Jaybird, and the lovely and friendly blue bonnets.

You could also hear from the swamp close by music from the swans and

ducks. There were a lot of emus, kangaroos, foxes, and wombats; and the

creeping lizards and brown and tiger snakes—a great lot of them. You had

to keep a good lookout for them. [There were] also prowling dogs. One day

the beggars found our camp and ate us out of house and home, even eating

the fat in the frying pan. To keep our eggs we had to dig a hole in the

sandy floor of our tent, but when we came to get them, they were gone. We

were blaming the snakes as the robbers. On leaving our tent for work,

Harry used to smooth the floor with a rake in case of snakes. If there

were any you would see their tracks. One day we were resting and smoking

on our beds [when] I saw a big sleepy lizard come in. I watched and he

went straight to our egg safe. I called Harry'' attention to him and said,

"There's our robber!" We caught him and gave him a dose of FlyTox stuff.

We were never troubled afterwards with him. Another time I felt something

biting me all night and, on leaving the camp, I felt the biting again. I

pulled up my shirt and a great green centipede dropped out. You could see

the marks of his bites around my waist. I got the wind up, but old Harry

said it was alright, they don't hurt you. I was a bit sceptical, but

nothing happened. Anyhow, we made 30 pounds each, and I earned a trip to

Adelaide.

We used to have fine evenings during the wintertime at

the Palace. A nice happy lot of boarders—Toby Sanderson, Ron Morris,

Dick Hunt, Louie McKenna—playing penny poker and telling ...

(illegible). Four years were spent happily there. There was always

something you could do—fishing; duck shooting; strolling around the

swamps to see the swans and ducks, also those strange birds, the drongos,

doing their dances; and fox shooting and plenty of sports. That's why I

like the SouthEast.

After the years had sped by, I felt a longing to see my

kinfolk again, and I came back to the city and lived with Nell and Bill

Long and, in 1948, came to live with Olive and Norman at Byron Rd, Black

Forest. Then Norman built at the foot of the range at 'Windemont'. I like

it there very much; a glorious view of the city. Then afterwards here at

80 Richmond Rd, Westbourne Park. While at Windemont, a stray dog [whom we

called] Larry came and stopped, and now he is my constant companion—a

great pet. While here, Bob and his Canadian wife came for a 12-month

visit. They are now back in Canada, and have a new addition to their

family, a great-granddaughter, Stacey.

So here I will have to stop my memoirs. I've a good

home, and very contented, although my wandering spirit often longs to see

the open spaces once again, but with the advancing years, "the spirit is

willing, but the flesh is weak". Still, I am lucky, though now in my 87th

year, to lay back and dream of the past. Having good health and everything

I want, and being with my kinfolk, being able to see them, and I wait for

the time when time will be no more, and then

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell

When I embark;

For though from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.

I cannot stop these memoirs without things that have

happened outside my working days, amusing or otherwise so

'Railway Bob'

Railway Bob was a German Collie and when he first came

into notice was when he was In a cattle truck with other dog shipped to

the far North to Cattle Stations. The guard of the train ferry took a

fancy to him, and after that he took him in the brake van. Bob liked

travelling and always followed him to work, and rode in the van, until one

day he took to riding in the engine. He was always, like his fellow

'enginemen', liking the open spaces. He was the only dog allowed, although

one Commissioner forbade it, but the men made such an opposition to it, he

rescinded his motion, but no other dog was to be allowed in future. So Bob

continued on his merry way and travelled widely to Melbourne, Sydney and

as far as Brisbane. At the completion of every trip, he always followed

the engineman home, and was an important visitor. When back in Adelaide,

he always went for a feed at the eagle Hotel and the girls always gave him

the best. Every traveller knew Railway Bob, and the children adored him.

(illegible) ... street with his bright collar. On it was printed 'Stop me

not, but let me jog, For I am Bob, the Drivers' Dog.'

I have had him follow me home from Kingston. He was a

very deserving dog. Some peevish drivers would put him off, and he knew

them and never got on their engine. I had a poem about him, but I have

lost it.

Home-keeping dogs have homely wits,

Their notions tame and poor;

I scorn the dog who humbly sits

Before the cottage door;

Or those who weary vigils keep,

Or follow lonely kine.

A dreary life midst stupid sheep

Shall ne'er be lot of mine.

For free from thrall I travel far,

No 'fixed abode' I own;

I leap aboard a railway car,

By everyone I'm known.

Today I'm here, tomorrow brings

Scenes miles and miles away.

Born swiftly on steam's rushing wings

I see fresh friends each day.

Each driver from the footplate hails

My coming with delight;

I gain from all upon the rails

A welcome ever bright.

I share the perils of the line

With mates from end to end,

Who would not for a silver mine

Have harm befall their friend.

Then other digs may snarl and fight,

Round cities purlies prowl;

Or render hideous the night

With unmelodious howl.

I have a cheery bark for all,

No tied my travels clog,

I hear the whistle—that's the call

For Bob, the Driver's

Dog.

He was lost for a time—someone pinched him. But one

day he brought him to a station, herding sheep. Bob heard the engine

whistle and ran to the engine, and the crew were glad to see him. The man

followed him and claimed him, but he made a big mistake, for on the engine

was Herman You, and he found it a losing proposition. He reckoned he would

go to law, but was told that the dog was the property of the Railways and

he would be sued for stealing him. Bob got killed by a butcher's cart in

Hindley St. He was stuffed by a taxidermist and he can be seen in

Tattersalls Hotel.

Among the amusing things I recollect was at Port Pirie.

After knocking off after a trip from Petersburg, my mate, Jimmy shrives,

and I went down to the Pirie Hotel, and George Coleman said, "We are

raffling a nice Christmas Goose at a shilling tomorrow." I told him we

would not be there. George said, "I'll throw for you." On our return from

our trip, we went down for a drink. Coleman said, "I threw highest for

you, Steve, so you had better get your goose. It's in the loose box, as

I've seen some of the stewards off the boat looking at it." So I went to

the loose box and looked, and there was a beauty of a goose [so] I grabbed

it and took it home. It was heavy. My father came from Moonta to visit us

and he had our Christmas Dinner, and Dad complimented me on the lovely

goose. That was alright, but a day or two after, I went to Coleman's pub

for a drink, and Coleman said, "Drink it up Steve and get." I enquired

what for, and he told me that Mrs Coleman had it in for me for stealing

her goose. Old George told me, "I've tried to explain to Ethel, but it was

of no use." It appears that someone stole the goose of mine and Mrs

Coleman had to ring ... (illegible) ... as soon as I could, but she was

waiting for me. "So you stole my goose!" and she gave me a slap in the

face, and then started laughing, so everything in the garden was

absolutely lovely.

While on the goose story, I recollect another one when

I was stationed at Bordertown. We went to live at Green's place. It was a

butcher shop at one time and had a lot of small sheds. Lol Spry of

Naracoorte gave me six goose eggs. I saw a big hen sitting on eggs in one

of the sheds. So I took the eggs from under her, and put the goose eggs

there. As time went on, one Sunday myself and Sandy Marshall were standing

at the stock yards, yarning with the publican, when the old hen came

proudly across the road escorting goslings. Well, getting towards

Christmas these goslings grew to a fine size. King the publican asked me

if I would sell them. I agreed and got 5/6 each, and I told him he would

have to buy the hen too. He said he did not want the hen as he had plenty

of fowls. But I was adamant. I would be no party to [separating] the old

hen from her family. Anyhow, he agreed and gave me 2/- for the hen. I

started to laugh, and he asked me what was the matter? I pushed the 2/-

back to him and told him I could not take it as it was his hen! He roared

a bit and said to me, "You know what you have done? I sent to town to

Padman Brothers for a setting of White Leghorn eggs and paid 25/- for

them, and you had the front of using my hen!' Anyhow, he said, "The joke's

on me, but the 25/- I gave you for the geese—you've had the trouble of

feeding them, so now I reckon we are quits, for geese are double the price

now to what I paid you!" All's well that ends well.

The best job I had in the Railways was the Cockle Train

at Victor Harbor. During Christmas time in 1920, we ran a train from

Victor Harbor to Goolwa for people to go to Middleton cockling. There

Norman met his doom, for he met Ollie.

Looking back, seeing the difference now at the present

time:

Gone are the comfortable little houses with their

paling roofs and fences and whitewash and the comfortable insides. Water—

all had their underground tanks. Goats—everyone had their goats for milk

and butter and cheese, and we boys had our billy goats and little carts.

We used to go out to the scrub and tell our carts (illegible)

Memories of Moonta and boyhood days, 18711878

I can remember Moonta Mines in my boyhood days. It was

thickly populated as the mines were at their top, and copper was used for

many purposes that have passed with the changing years. During that

period, telephones and telegraphs were in their infancy. Sailing ships'

bottoms were sheathed in copper, and [in] various other things, copper was

used. The scrub at that time circled the mines.

June 21st:

For months we used to go out on Saturdays for green

mallee and stock up for a bonfire on that day, with fireworks and

potatoes. Also in their season, we could go out for wild cherries,

quandongs, cranberries and (illegible). We always carried a pannikin with

us, and if we got thirsty, catch a nanny goat and milk her. They were

happy days for kids.

Sunday School:

We used to have an Anniversary every year, and get a

cake and sweets, and march with a brass band. The annual Show on the old

Showgrounds between the Mines and the township, and the old horse tram

from the Mines to Moonta Bay on Boxing Day to see the regatta. Bakers and

butchers and greengrocers all came to deliver goods in their horse and

van, and cabs running from East Moonta to the township. All gone. Now

Moonta Mines is like a ghost town.

Wesleyan Methodist Church, Moonta Mines SA

VERSION 2

I often, when I go to my rest or smoking my pipe, start

thinking backwards of things, scenes and events in my past that has

happened to me—from the slow, old days and of the present days of hurry

and restlessness—so this is the story of my life.

1871

I was born at Moonta Mines on the 4th of

July 1871. My Father was born at Breag, my mother at Redruth, Penzance,

Cornwall, so you see I am of the old Cornish stock.

Moonta Mines

My childhood days I can clearly remember. I can see in

my mind the house I was born in. It is still standing with its villa

front, a fine house for those times. In those far-off days, Moonta Mines

was at its peak for copper was at its highest price, for at that time

telegraph and telephones were in their infancy, and all wooden ships had

their bottoms sheaved (sic) with copper. Moonta Mines was noted for

richness and plenty in accordance with Wallaroo Mines, but the advantage

of the above was soon lost by the productions of other alloys and the

discovery in the Argentine, South America and other lands, so the high

prices tumbled down to a low ebb. I can still hear the tones of the

clapper at the Pits Head for the rise and fall of the buckets hauling and

discharging the ore. Other memories of those days [are] the singing of

those dear old Cornish voices at the churches and after[wards] the young

people walking up and down the road from the Mines to the township was

rich and lovely; the blending of those young voices for Moonta was, in

those days, noted for its choir and singers.

My school days

I started very young, one of the first school of Miss

Holman and on the complement of State Model School. I was one of the first

scholars in the infant class under Miss Errington. Dr Torr was the

principal. One of my earliest recollections was our first removal to

Adelaide in 1875. We lives at Barton Tce, North Adelaide while my father

was employed in the Government Service. I was only five years old at the

time. We did not live in Adelaide very long but went back to Moonta Mines

where my father was underground and Surveyor and Draughtsman under Captain

Hancock. I can also remember in 1876 the centenary of Sunday Schools.

We migrated to Adelaide again in 1881. I was 10 years

old. Father had again come back to the Government Service in the Water

Conservation Department under J W Jones. We left Moonta Mines, mother and

I and all the kids and furniture in a wagon and team driven by a farmer

from Kadina named Reuben Cox, through Port Wakefield—where I saw a

railway engine for the first time—through Wild Horse Plains, Inkerman,

Dublin and then to Adelaide to live at Toronto St, Ovingham. I went to

school at Tynte St, North Adelaide under Mr Gill. Mr A Hardy was my

teacher. I got 2nd at leaving examination, 98 to Steve Allen's

100. My prize was beautiful bound book, 'The Last of the Redman'.

After leaving school, I entered the Water Conservation

Department in the new Government offices. While in the Water Conservation

Dept, I went with J T Furner surveying and levelling for the Millbrook

Water Scheme from Woodside, Lobethal, Cudlee Creek to Millbrook. Also [I

went] north with Mr W Porter surveying and levelling over Palmer Hill,

Tungkillo, and along the foot of the ranges to Millendilla Creek.

Surveying Department

In 1888, I travelled to Port Augusta and stopped at the

Junction Hotel, and travelled next day by the mail buggy to take up my

duty at the survey camp at Yadlamalka along the east side of the Flinders

Range towards Worrokimbo Marachowie Station. Our next camp was to Mt Eyre,

a deserted township on the old overland route to the Territory. On our

completion of work there, we shifted to the eats side of the ranges. At

Stirling North we camped for a couple of days to rest the horses. I went

into Port Augusta with Mr Mills and stayed at the Flinders Hotel. We left

there with the spring cart and tandem pair, Bantam and Bolivar, and went

through the PitchiRichi Pass to Quorn and caught [up] with the rest of the

party and then went to Tee Ti Va Spring at the mouth of the Depot Creek

Gorge. Depot Creek Gorge runs through the range from the east side to the

west side, a very picturesque chain of very deep pools of water—very

cold and a great spot for the euros and rock wallabies and dingoes.

Our work there was surveying along the ranges. While

there we were invited to a party at Ardenvale, the population chiefly of

German settlers. I had my first sleep in a German bed—feather mattress

under you and a thick German quilt full of feathers, very nice, warm and

comfortable. I climbed to the top of Mt Arden and rebuilt the Trig of

stone. The view from the top of Mt Arden was a glorious one, looking over

the saltbush plains to the West across Yadlamalka to the Tent Hills of

Nonning on the west side of Spencer Gulf. To the south [was] Mt Brown, and

the Pass to the east to Mt Ragless, to the pocket to the north where lay

the stations of Worrokimbo and Marachowie and Mt Eyre, and away in the

distance Mt Desolation. At that time the salt plains abounded with

kangaroos—the big red jokers—and the ranges [were] thick with euros

and rock wallabies, not forgetting the dingoes and wild dogs and the

birds, the crow dominating. So there was plenty of sport for the rifle,

and good money for skins.

After finishing our work there, we travelled through

the Hookina Pass to Mern Merna Creek for camping. Mern Merna Creek comes

from the Wilpena Pound which lays back behind St Mary's Peak and Mt Alex.

While there, the creek came down a banker owing to heavy rains back of the

range. Also some splendid quandongs were ripe, and Sturt Pea blooming.

{When] finished there, we travelled north over the Brachina and Bunyeroo

Creeks to Parachilna, and camped at the Breakfastime Dam and surveyed the

country to old Wilpena Station, and as far as Breakfastime Creek. [We

then] broke camp and went to the well at the mouth of the Oratunga Gorge.

I may say, while camped at the above places, a very severe drought was on

that year (1888), and it was a pitiful sight to see the poor sheep bogged

in the mud of the drying dams and the crows (the black blaggards) picking

the poor things' eyes out. [The] only thing you could do was to shoot

them. Also kangaroos, euros, wallabies, and wild donkeys all round the

camp, smelling the water in our galvanised tank which held our drinking

water for ourselves and horses.

While camped at the mouth of the gorge, we went to

Blinman for a cricket match, and won it. Our team was made up of three

from our own camp, Cosagee and Hildoo from Bob Calwell's camp, and the

rest from D'Alles(?) road gang. Cosagee was our star batsman, a great

cricketer. He had been a member of the Bombay Cricket Team that had played

in England. I recollect the Blinman Hotel where they gave us a fine dinner

of kangaroo tail soup and quandong pudding. The hotel was kept by

Remington Barnes who afterwards won a Birthday Cup with a horse called

Shootover. Incidentally, once while working a passenger train to Karoonda,

my mate Jack Maher and I went over to the hotel for a drink [and] looking

up saw the licensee's name over the door, 'Remington Barnes', and on

entering the bar saw a picture of Shootover. I made the remark, "Remington

Barnes. That sounds like Blinman." The old gentleman standing behind the

bar remarked, "I'm Remington Barnes, and that was my horse,

Shootover."

Then we entered into conversation, and we could have had the pub.

After finishing our work there, we had orders to bring

the camp to the Survey Yards at Adelaide. The Oratunga Gorge runs through

the range to the Blinman and in it is the famous Red Ochre Gorge, a paint

that the old time niggers travelled from 100 miles around to get the red

ochre to paint themselves for their corroborees. The track down to

Adelaide was uneventful. It took us a week or so. We travelled through

Craddock, Mananarie, Red Hill, Yalina, Terowie, Black Spa(?), Kapunda,

Sheoak Log to the Survey Yards, and disbanded. I still remember the names

of our party: Mr W W Mills, surveyor; Jack Fotheringham and myself as

chainmen; H Edlen, teamster; Newt Gregory, cook; and Sam Moore as axeman.

(illegible name also inserted).

I also went with my father surveying around Baldina

Plains, and then with J T Furner on the pipeline survey—Crystal Brook

through Red Hill, Collinsfield, Lochiel, Buntunga over Barunga Gap down to

Bute. My last trip on the survey was with father on the deep drainage

survey of Eastwood, Parkside, Unley and Wayville, so you can see that I

had a very busy time for about 6 years. I was then in my 20th

year.

Diamond Drills Well Boring

I then tried my hand as an engine driver on No 1

Diamond Drilling at Willochra, where we struck a good supply of water,

then transferred the plant to Richmond Valley on the Forest Reserve at the

foot of Mt Brown, and stopped there until the finish. While there we

visited Quorn often on a Saturday, playing football, and ambled around the

rim between the camp, overlooking the Pass, with the Devil's Punchbowl

standing up in the middle of the Pass to the Dutchman's Stern near Depot

Creek. You had to go about carefully on account of snakes as the place was

alive with them—carpet snakes, tiger snakes and the deadly death adder.

I remember, while camped at Richmond Valley, the mice plague. They came in

countless numbers and then the snakes had a wonderful season. Our beds

were made from chaff bags, and we became quite used to feeling them under

us, but [we] were careful to see the tent was free from snakes before we

turned in. The members of our party were Jack Anderson, boss; myself,

engine driver; Bill Caroline, driller; G Mallin and Henderson, cook.

1890-91

Railways

I joined the South Australian Railways in March 1891

and was stationed first at Islington, not thinking that for the next 46

years I would end up as an engineman. I did not stop long at Islington,

and it was all night work—6 pm to 6 am—for 4/6 a day. Then I went

rambling over the country once more, and I was transferred to Petersburg

(now Peterborough). I was then sent on to Cockburn on the border of South

Australia and New South Wales. There I struck another year of drought.

This time it was rabbits dying of thirst everywhere, taking its toll of

Typhoid Fever. It was a hard life, dust storms and everything that was

hard. We had to live in tents with a stove in the open air to do our

cooking. Our washing a kero tin bucket, a cake of Velvet or Sunshine soap,

our clothesline the border fence. It was very trying to find out in the

morning that a dust storm had come up and our clothes [were] strewn all

around the country. But in all of it, we enjoyed ourselves in a way with

yarning, singing and telling of anecdotes and joking—of which I was one

of the sufferers ([which] I will relate at the end of my journey).

After a few months at Cockburn, I was stationed at

Broken Hill. Broken Hill in those days was wild and woolly, a real

cosmopolitan town and a mixed town of the lost 7 tribes of Israel—

Greeks, Turks, Cousin Jacks, and all the breeds in the world—and you had

to be careful of what you said and did. While at Broken Hill I had my 21st

birthday, and had attained my manhood, getting 6/6 a day. While at Broken

Hill I had my first trip as Fireman with driver Eustace Bayliss on the

express Broken Hill to Cockburn on a Yankee Engine No 48. Also [I had]

several trips on a Sunday to the Rat Hole, a well at Umberumbeca, with the

water train as Broken Hill had a water famine. Stephens Creek, their main

water supply had dried up. We filled the travelling tanks and emptied them

at Sulphide St into troughs where the populace bought it by the bucket.

Clothing as very cheap as NSW was free trade and SA was protection. You

could buy a shirt for 1/- to 3/-, wear it Sundays and then the weekdays,

then burn it, as washing would cost you 3/6 on account of the water

famine.

While at Broken Hill the big strike started in 1892.

Sleath and Ferguson were the leaders and got gaol terms, and everything

was at a standstill, and we were taken away and sent to different

stations. I was lucky, being sent to the SouthEast. They took me off at

Naracoorte and sent the others on to Mt Gambier—they were Jack Sharpe

and Harry Liston. I was kept at Naracoorte and, after a while, transferred

to Bordertown. While there, I sustained a broken foot while turning a

narrow gauge engine on the turntable. The turntable had a third rail

between the two rails of the broad gauge, and I was tricked, getting my

foot caught by the third rail and that put me aside for several months. On

my return to work, I started again at Naracoorte, doing light duties in

the shed for a while, and then went on the road between Naracoorte, Mt

Gambier, Kingston and Bordertown. It was there, as the old song says, 'I

met me doom'. I courted and married Miss Edie Long and then started

another life.

While in the shed at Naracoorte, Mr Grurbach (?) the

foreman taught me the setting of engine valves and that stood me in good

stead in after years, as when they gave me my send-off on my retirement.

The valve fitter at Mile End [said] that, when engineman Quintrell booked

the valves to examine for re-setting and other faults, he knew what he was

booking, and I would get to them immediately and found that he was always

right.

In 1894, I joined the Masonic Lodge at

Naracoorte, and

in that Lodge, I went through all my degrees, and now, at the present

time, I have been a Mason for 60 years. I was transferred to Kingston, and

Roy was born there on 13th November 1894, and I was a proud

father. Kingston has always had a charm for me, for my happiest times were

spent there by the sea, fishing [from] jetty and boat, and gathering rare

shells on the beach. [There was] cricket and football and I was captain of

both. At Naracoorte, Ralph was born—November 7th, 1898, and

also Norman, 1902.

While stationed at Kingston, 1897, we had severe

earthquake shocks which continued for several months. Also a tidal wave

came and piled up the foreshore with seaweed. [It was] 30 feet high and

nearly reached the road—very lucky for Kingston it did not. Before the

shock, Kingston had a nice beach, but now there is no beach for a mile

each side of the jetty, and it has caused the land to encroach onto the

sea for several yards. The shocks were supposed to arise from a submarine

volcano off Cape Jaffa. While at Kingston (1900), the Boer War started and

the Bushmen's contingent went to the Transvaal. Also the Protection

Gunboat went to China [for the] Boxer Rebellion. One of the crew was

Charlie DeLongville from Kingston.

My mate at Kingston was Charlie Hall, (long since

dead), [and] guards T Ryan, George Elsey and Charlie Gust. I was then

transferred back to Naracoorte and there had my first trip as an

engineman, Naracoorte to Wolsely and back, my mate being Bert Rumball, on

an Engine W Class 56. In 1903, I was transferred to Mt Gambier. Times were

very bad—a Depression. A lot of us [were] re-graded and I was one of the

unlucky ones—to a cleaner again at 6/6 a day. As a fireman, I received

8/- a day. I was discontented with my position and wanted my right share

of firing, as junior men to me up north were doing superior work, [so I]

put in my application for Port Pirie, and got it, so I was back up north

again. While at Mt Gambier I saw the opening of a tower at the top of the

mount.

1904

On arriving at Port Pirie, I was surprised at the shops

[on] one side of Ellen St, and the other side [were] the wharves and

ships, with the train running down the street. I was stationed at Port

Pirie for 7 years and in 1911, I was sent on to Petersburg to take my

place as an engineman. At Pirie, we made many good friends—the Dalys,

Helliers and Milnes—and the friendships last until now.

Petersburg

Working on the Cockburn road, also Petersburg and Quorn,

Pt Pirie and Hamley Bridge: I will try and pick up notes at the end of my

working notes.

Working on the Cockburn road was a long, tiring trip of

14 hours and upwards, but on return to our home station we had 24 hours

off, and did 2 trips a week. We had to put 12 Sundays away from home and

13 home at Petersburg. It was a hard road and we had many different,

difficult jobs to contend with—dust storms, grasshoppers, grubs and

ants, washaways and wind, but it was 'all in a day's work'. While at

Petersburg, World War 1 started in 1914, and Roy went to Palestine with

the 9th Light Horse. Also, my only brothers—Clarrie, Jack and

Dick went. Roy returned at the Armistice after 5 years in the desert,

but my brothers remained behind, two buried in Flanders (Clarrie and Dick)

and Jack at sea.

In 1916 I was transferred to Mile End and remained

there until my retirement in 1936 after 50 years government service. At

Mile End I worked all suburban lines, Adelaide to Tailem Bend, Karoonda,

North, Victor Harbor, Mt Pleasant, Sedan and Willunga lines, passenger,

freight and express, until my retirement. I had many experiences, some

I'll relate at the end of my task. I have fired and driven many classes of

engine on narrow gauge—L, K, R, RX 500, Mountain Type 600, Pacific, 700

Mikado, and (illegible). I retired in 1936 and had a good send-off and

presents, one of which I treasured most—a gold Dennison watch from my

mates I worked with. So that's the end of my working life. 'Rest after

toil'.

Incidents, humorous, accidents etc which I'll try to

recollect

An old school mate of mine, Bob Abrahams, was station

master here (Cockburn) and when he heard he had an inspiration. The

Chargeman, Ned Boscene, bought a violin and wanted to learn to play it.

The Quintrell family of Bellringers had just made a tour of the North and

Broken Hill, so Bob had a conversation with Bozzy, and told him that I was

one of them and a fine violin player, and he ought to get a few lessons

from me, but not to take any notice [for] I may make out that I could not

play it. Anyhow, when I arrived there, they told me about the joke and

left me to it. Bozzy collared me immediately I arrived to give him a few

lessons, and nothing I could say about not being able to play it would

convince him. I stalled for a time and then promised to give him lessons.

[I] had a job to put him off but one day I went to my slaughter. In

passing his tent, he called me in and put the violin in my hands. I

fiddled around with it until I broke a string and then told him I was

sorry, but the violin was no good and I didn't like a second hand fiddle.

He took it quietly until I got up to go away and, at the door, helped me

along with his foot. That made me very angry. He was a big burly Cousin

Jack, and I had no hope of tackling him, so I gathered a heap of stones—

of which there was plenty of them—and bombarded him every time he tried

to come out. It was a shame to what he would do to me when he got me. Mr

Hill came along and asked what I was up to, so I told him, and as he knew

of the joke, all I got from him was that I deserved it for keeping up the

joke and humiliating Boscance. So I raised the siege, and we were good

pals afterwards but my reputation as a musician was blasted.

Accidents

Many. First my broken foot, then a collision at Wolsely

between our goods train and the Melbourne Express caused by the driver of

the Express running into us. We were between the Home and Distant signals

and ran past the Distant at 'Danger'. Result: shock and bruises.

At Kingston: train ran off the main line at loco

points: shock and face injuries.

Petersburg: collision at points caused by Big T engine,

'Big Ben', standing across our line. The signals were for us from Port

Pirie. My mate was Alf Holthouse. Result: injuries to head and ribs and

shock.

Mile End: The biggest between Walla and Callington. I

was driving the East-West Express and the bridge was washed away by a

terrific cloudburst.

Also at Petersburg: stopping a train of ore that ran

away in the shunting yards and running to the loco shed. I was highly

commended for that.

A few minor ones not worth mentioning. One stopping a

train on emergency stop on the Henley Beach line. A little child play[ing]

right on the ballast. Did damage to the train. I could go on, but I think

that's enough.

Mile End

[From] 1916 to 1936, I was working on the freight and

passenger trains on all lines on all classes of engine from the smallest

to the biggest. My life has been, on the whole, varied but if I had my

time over again, I would do it and enjoy it, for like Adam Lindsay

Gordon's poem [see above].

Port Pirie

Pt Pirie was, at that time, dirty, smoky and very hot

in the summer—not much humour but it was enjoyable.

Petersburg

I retired at the age of 60, and sat back to enjoy life,

but my good luck in life deserted me on the death of my dear wife Edie.

After 14 months of illness, which she endured with patience—womanlike—

and since then I have lived with my own folk, with the exception of a few

years at Kingston with the Hayes family, pottering about, doing a bit of

fishing and shooting with Harry Cooper who was killed lately by a

collision, the ... (illegible) ... he was riding at the Glandore

crossing. Wattle bark stripping at Wangolina, making good money. Also, for

a few weeks, looking after and supervising Italian prisoners of war.

I enjoyed once every month travelling through the

Coorong, Meningie and around Lake Victoria district with Walter Smith. He

was a skin buyer, meeting a lot of settlers and farmers, and at Point

McLeay Mission Station. I had two experiences while travelling with him

going around Lake Victoria. At one place, Jack O'Connor's missus spoke to

me and asked if I remembered her. [Document ends]

A fragment:

... prominent people as LeHunte, Governor of South

Australia, and Commissioner of Railways, and fired on the equiped with

different spark arresters they were trying in the south, as they were

blaming the railways for fires starting from the railway lines. Several

types made by outsiders, all of them thinking that they had the idea from

stopping, as they said, the sparks from the tunnel. But they had to come

back to the old flat type in the smoke box. Also ran, for a fortnight,

Fitzgerald's Big Circus from Bordertown to Naracoorte, Penola, Mt Gambier

and Millicent. Fitzgeralds hired the train and engine driver and fireman

and guard for the round trip. I had a good time, good food, and seeing all

the performances. I got sick and took up the ticket for something to do. I

also had charge, while stationed at Adelaide working the Mikado with the

first booster installed.

There are plenty of the study of characters on the

road, amusing and otherwise, especially on the Melbourne Express. At

Adelaide on arrival, there was always a detective stood by the engine,

another at the rear of the gate, and another top of the stairs and ramp,

so any known criminals had little hope of getting away unobserved. I saw a

fine looking woman, dressed lovely. The detective standing by the engine

said to me, "She looks nice, don't she? Well, she won't get far. She is

one of the biggest procurers in Australia".

Once on the Cockburn road my mate ... (illegible).

It was a bitter cold night for a young kangaroo and he wanted to take it

home. We put it in a bag at the back of the ... (illegible). I went

to see how our young passenger was, but he was frozen stiff. We got him

down to the firebox to warm him up, but he kicked the bucket. So when we

got to Mannlill, the signalman was down at the long road to let a train.

There was a fire in the waiting room, so we put him in a chair and sat him

up and left him—a great mystery, how the kangaroo got there, and to this

day, I do not know what he died of—heart failure, or fright, or

exposure.

Stephen William Quintrell died in 1960, aged 89

years. He was survived by his three sons—Roy, Ralph and Norman; five

grandchildren—Warren, Ruth (now Ruth Needs), Jeff, Bob and Neil; and

nine great-grandchildren.

L Neil Quintrell

9 Woodburn Ave

Hawthorndene 5051

Ph 08 8278 4253

Email: neil@quintrell.net

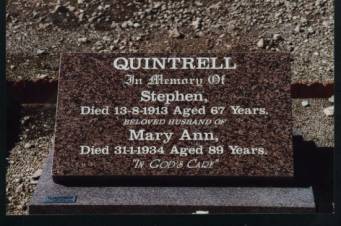

the gravestone of Stephen William's parents Stephen and

Mary Ann Quintrell at Moonta SA cemetery

gravestone of Rosina and Mary Jane

Quintrell, Stephen

William's sisters at Moonta SA cemetery

gravestone of Alice Emma and Violet

Quintrell, Stephen William's sisters

Moonta SA cemetery

The stories of Stephen William's three brothers,

Clarrie, Dick and John who died in World War 1 are told in separate

stories. See Clarence H Quintrell,

Richard H Quintrell and JAQuintrell and WW1.