To the readers.

Please excuse briefness. Owing to the war, economy in ink & paper must be studied.

In commencing I will go back to July 17th 1915 on which day I traveled from Pt. Augusta to Adelaide for the purpose of presenting myself before the recruiting staff at Curry Street. After a Dr commented with another Dr on the teeth I have not lost they came to the conclusion I was a fit and proper person to be member of the AI Forces. After spending a few days in the said city I returned to Pt. Augusta to fix up what I had left undone.

On August 9th I found myself again in the train going to Adelaide. On the 11th I again visited Currie Street. After a considerable wait I was sworn in & marched off to the Exhibition Camp. There one received blue dungarees white hat blankets & various other items. We were drafted off into sections & shown into our sleeping quarters which were marked Prize Cattle. Everything was white washed & looked clean so one soon settled down to a recruits life. Well readers I won't dwell on camp life too much longer. After a course of training forming fours route marching etc. at the said camp at Morphetville I went to the Mitcham Camp to the Signaling School after a course of flag waving, buzzer practice & lectures. Time passed until we find ourselves in the month of Dec 1915. About the middle of that month our O/C asked for 5 volunteers for the 2nd Div Sig Coy

The writer stepped out with others and four others and self were chosen. We were informed we would probably have to go immediately without our leave. Luck had it however we got our Xmas leave. I again found myself home dressed in H.M. uniform. After spending a few happy days home Dec 28th arrived on which day the sun didn't forget to rise too and needless to mention made its presence felt on the journey back to Adelaide. Arriving somewhat tired and hot I searched in the city for a bed for the night. After a considerable hunt I found a vacant room in a hotel. If I remember rightly it was the Black Bull or John Bull. However I didn't worry about the name as long as the bed was clean which I proved was.

On Dec 29th at 4pm or thereabouts we were seated in the Melbourne Express waiting for time. Our party were 10 all fine fellows. Some of them had their people down at the station to say farewell to them, a sight I don't like witnessing. "Hour" the whistle blew. Seats please said the guard. The green flag was shown to the driver and we waved farewell to the folk remaining on the platform.

On the morning of the 30th I awoke in time to get a bit of breakfast at Ballarat. A sausage and piece of bread and cup of tea. "2/- please" "Thank you", good morning and we proceeded arriving in the city of Melbourne about 10.30am.

After waiting about on the station for some time we were marched off to the Domain camp. We immediately applied for our final leave, but that unfortunately was not granted us. However the O.C. Signals gave us practically most of our time in Melbourne off with the exception of about a couple of Musketry parades and rifle shooting at Williamstown and so the old year dies out and new year of 1916 comes in. Very quietly and orderly (were) the streets of Melbourne on the early morne of the new year.

We 10 S.A. Took advantage of our time in Melbourne and saw as much as we could of that city. The people seemed very kind. I visited St. Pauls Cathedral, also places of amusement.

January 5th 1916 arrived. Up bright and early kits packed. Fall in roll call quick march to the station we go, entrain and proceed to Pt. Melbourne, disentrain and march to the pier. Citizens are crowded each side (of the) road as we march down. We arrived on the pier and there awaits our transport A19. (Embarkation records show that he departed on the "Afric" from Melbourne 5th January 1916.)

Troop transports were requisitioned by the Commonwealth government for the purpose of transporting the AIF overseas but in addition to carrying troops, horses and military stores they also carried wool, metals, meat, flour and other foodstuffs, mainly for Britain and France. The fleet consisted mainly of British steamers and a few captured enemy ships.

We embark and steam off at midday (to) the waving and crying on the wharf of the parents and sweethearts of the boys who were leaving. To the writer they were all strangers but still he cannot forget it.

We steamed for some hours and then anchored off Queenscliff whilst some repairs were done to gear. Whilst waiting, motor boats, sailing boats, rowing boats came around us all full of cheerful folks of the fine sex.

About midnight our transport steamed off again and thus we steamed. It was on the 11th that we again sighted land. Some excitement as we thought we going to call at Fremantle. We were disappointed however as we awoke next morning still steaming and it was on Jan 22 at 5.30pm land was again sighted. Great excitement again at 6.30am on the 23rd we steamed into the Port Colu.

During the afternoon we had a few hours ashore. We purchased some bananas coconuts & visited the Barracks and other places in the short time we had ashore. We were disappointed next day we were not allowed ashore. On the 24th at 10.30pm we again proceeded on our voyage and nothing of interest to report. We passed through Hells Gate on the morning of February 3rd to the Red Sea. During the day the SS Borda passed us with SA troops on in charge of Col Powell. We signaled to her with flags and found out that much information.

On waking on the morning of February 8th we found our transport anchored in Port Suez and we remained anchored until the morning of the 10th. At 4pm we entrained and journeyed to Zeitoun. The journey from Suez to Zeitoun was not very picturesque. Camps were all along the line. On the canal side there were green patches.

The Second Division

In June 1915, the General Officer Commanding the Australian Imperial Force, Major General John Gordon Legge, put forward a proposal to form a Second Division from units training in Egypt. This proposal was accepted by the Australian government on 10 July 1915 and Legge designated Brigadier General James W. McCay to command it. Unfortunately, McCay broke his leg the next day. Legge then took on the job himself.

The Division was formed in Egypt July 1915 and moved to Gallipoli in August, serving there until the withdrawal to Egypt in December 1915. In March 1916 it was the first division to move to France, taking over part of the "nursery" sector around Armentieres. On 27 July 1916, it relieved the First Division at Pozieres and captured the Pozieres Heights at great cost. Two more tours of the Somme followed in August and November.

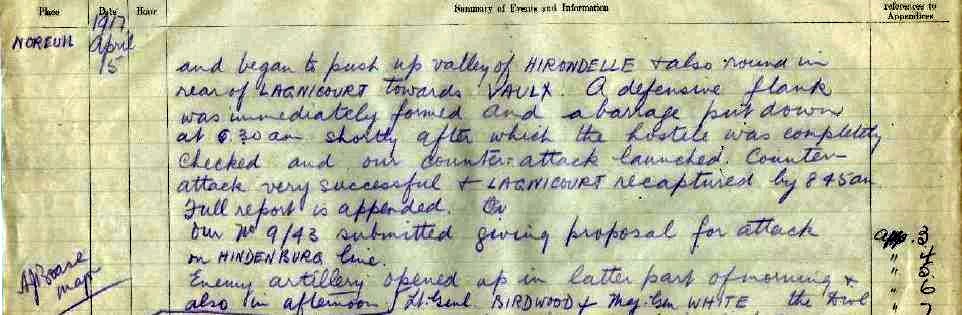

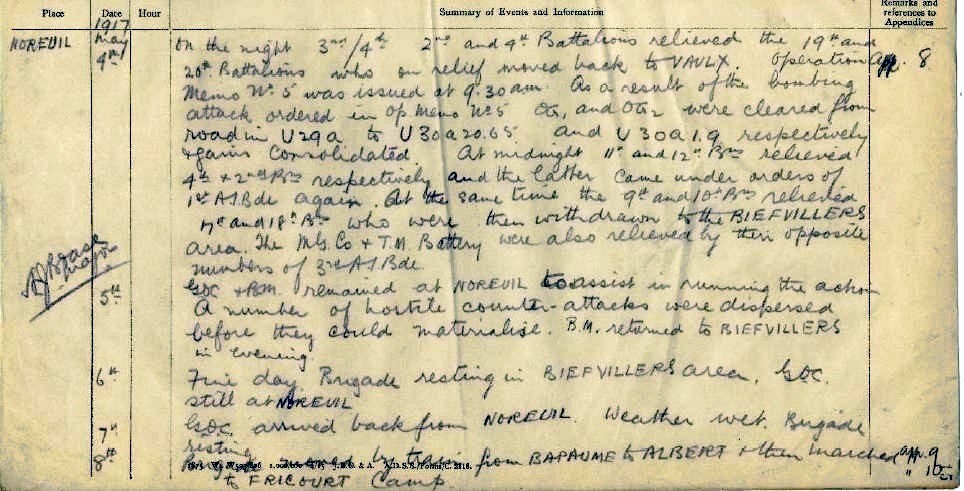

In March 1917 a flying column of the Second Division pursued the Germans to the Hindenburg Line. At Lagnicourt on 15 April 1917, it struck by a powerful German counterattack, which it repelled. On 3 May 1917 the Division assaulted the Hindenburg Line in the Second Battle of Bullecourt, holding the breach thus gained against furious counterattacks. During the Third Battle of Ypres, it fought with great success at Menin Road in September and Broodeseinde in October.

In March 1918 the Second Division helped halt the German offensive in the Somme region and fought in the Battle of Hamel in July and the Battle of Amiens in August.

In September 1918 it took Mont Saint Quentin by storm in one of the finest feats of fighting of the war. It fought on to the Hindenburg Line and beyond, becoming the last division to be withdrawn.

As part of the Second Division, Verner may have been at the front line in these well known battles. This diary gives his experiences at

Pozieres,

Lagnicourt and

Bullecourt.

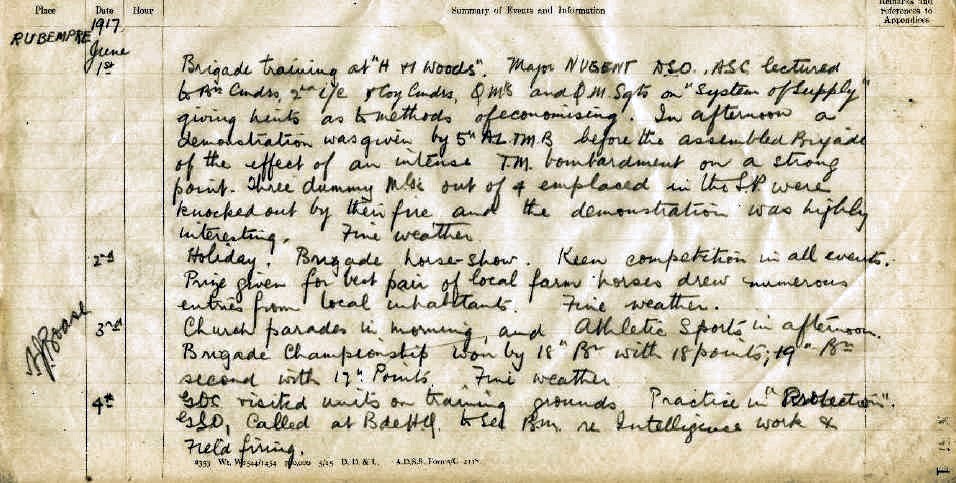

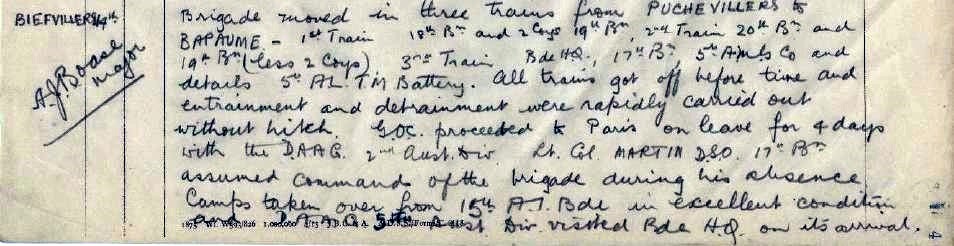

Although he was in the 2nd Signal Company, part of the 2nd Division Engineers, he was attached to the 5th Infantry Brigade which was comprised of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Infantry Battalions.

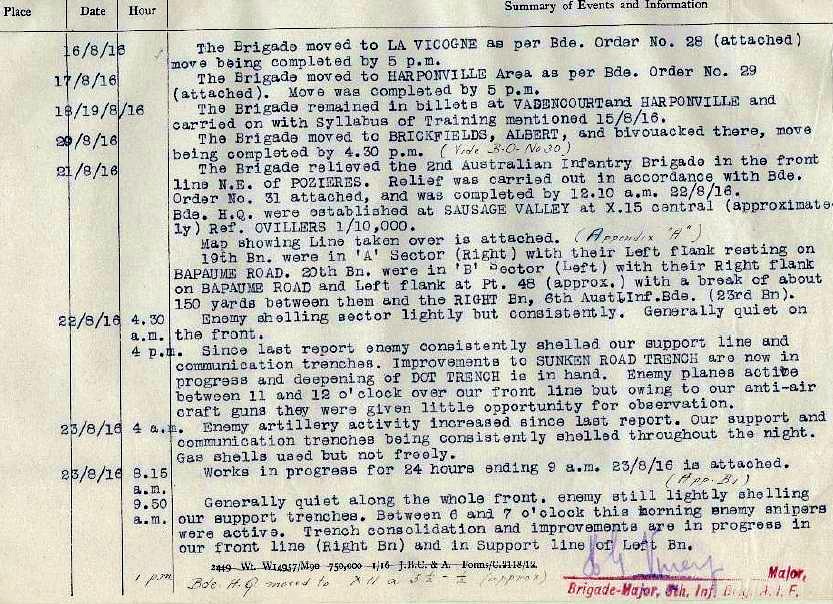

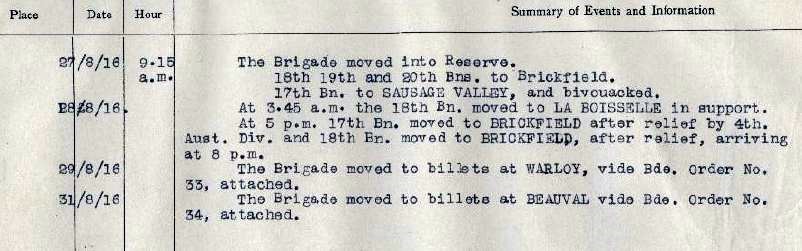

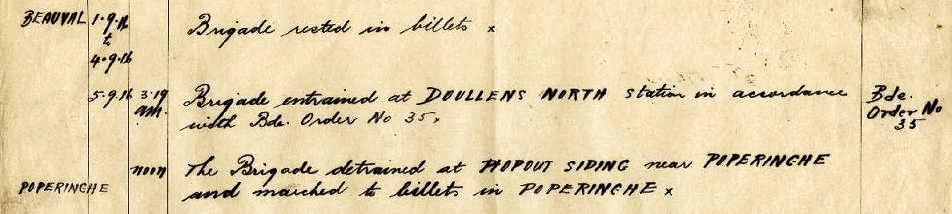

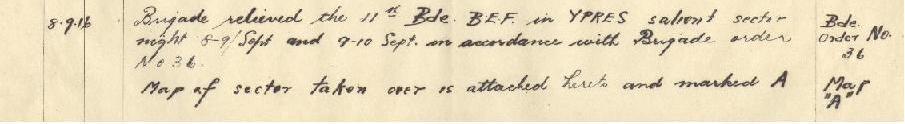

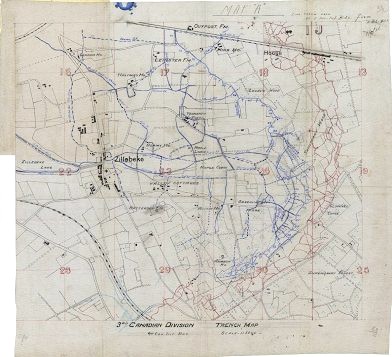

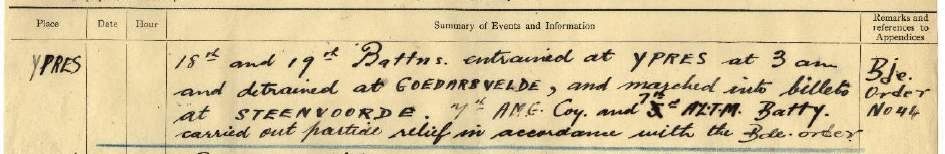

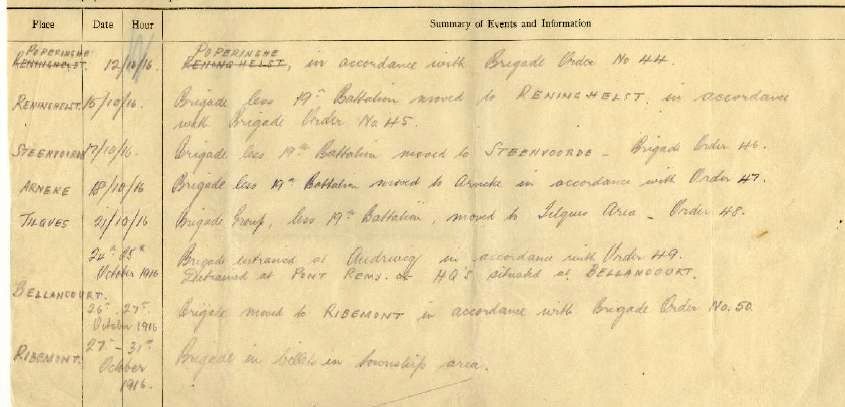

Because he kept careful record of his movements on certain dates, we can correllate these dates with the movements of the Battalions as recorded in the 5th Brigade diares. We find :

27/08/16 - 18th,19th,20th - Brickfield (either 18,19,20)

06/10/16 - 18th,19th entrained to Ypres (either 18, 19)

15/10/16 - bde less 19th to Reninghelst (must be 18)

From these movements and the places he mentions, we can work out that he was most likely attached as a signaller to the 18th Battalion and was moved with them.

Click here for a summary of the 2nd Division and here for a short history of the 18th Btn 1st A.I.F. which includes much more history than the time Verner was with them.

Since the diary ends in August 1917 and he did not return home until May 1919 only a careful study of the

Brigade diaries would show here he was.

At 11.30pm on the 10th we arrived Zeitoun. My first duty was next morning to send cable home to the effect that all was well. Our first place of visit was to Mary's Well tree and church. Evening Heliopolis 12th visited Cairo. I took advantage of my time in Egypt and visited all I possibly could of the ancient places. Pyramids, Mosques, Citadel etc. On March 7th our late pal Bert Siddell took bad and taken to hospital on March 15 our mate died. On the 16th our friend's remains were buried in the Cairo cemetery. I meet his Bro(ther) at the grave and went back to Cairo with him.

Volunteers were called to go away, no-one knew where. 14 were required. I was one of the fourteen and it was on the wee hours of morning March 21st we marched out of Zeitoun Camp to a siding to entrain. Our trains left at 7.50am and at 8.10a we again proceeded and each one was guessing where we were going. However at 1.30pm it was quite clear we were going to embark as we steamed into Alexandra. Transports were plentiful in the Port and at 2.30pm we were on board our transport TG062 or the name SS Oriana. At 6pm ropes were set free and we steamed out. Everyone seemed satisfied we were on our way to France and thus we proceeded with an escort some distance from us. On the 24th we stopped outside of Malta waiting orders but soon proceeded on our journey again. The food was very poor compared to what we received on our previous transport the "SS Afric". Our hunger has perhaps increased.

We were steaming in zig-zag course to dodge submarines and wearing our life belts all day. Submarines however kept away from us I am thankful to say and so we are in Marseilles 5.30pm on the 26th March quite a pretty entrance. We stayed on board that night and on the following day at 12-15pm we marched off the wharf and entrained 2pm.

The main danger to the troopships was from German submarines (U-Boats) and night watch was kept for submarines on their trip to France.

Our destination in France was still unknown to us so we journeyed on through beautiful country and important railway centres. French people appeared delighted to see us waving as we pass through the various stations. It was a station called St. Roch that I had my first snow ball fight and our journey went on until 10.15pm on the night of the 29th when we disentrained at Etaples. On arriving there Tommies were practically the only troops there and Australians were somewhat a novelty. On April the 6th our friend Norman Wauchope got the mumps. Which to our sorrow we in the same tent were isolated for a term of 21 days.

On the 12th Scotty got mumps and out time dated from the 12th and on the 24 another member got them and so we stayed on. On 25th we were all calmly sleeping about midnight there was a terrible explosion followed by others. On poking our heads out of the tent Mr Zepp was dropping some of his iron pills however although he was close to the Hospital no damage was done. It was on June 13th that we were released from isolation camp making our stay there of 75 days. During that time there is nothing of interest to relate.

Parades and route marches were our daily routine not forgetting stew for dinner every day. Since we came out of isolation we were anxious to join our unit and we tried very hard to get away. On July 15th we proceeded to ABBEYVILLE and somehow that relieved us as we were tired of ETAPLES.

In March/April 1916, the AIF moved to northern France and went into the line south of the town of Armentieres. Here, the soldiers learned about the art and weaponry of static trench warfare. Conducting raids, manning trenches, sniping and directed artillery actions.

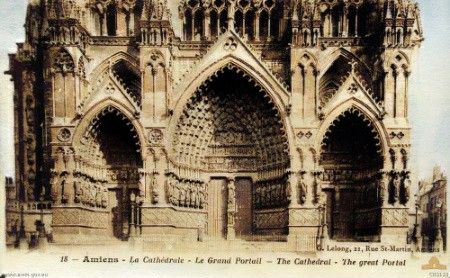

We arrived at Abbeyville about 9.30pm. This town was rather a nice place and very pretty. We were under the Tommies there and the base staff were of a good kind. There were NZ, South Africans, Australians, Canadians and Tommies. Quite a variety but all worked well together. It was on July 28th anniversary of the date of my enlistment that I proceeded to AMEINS to see my Bro(ther) Sapper GEO Sanderson and needless to mention we enjoyed ourselves for the short time we were together.

We visited the cathedral and purchased some photo of the cathedral and posted to Dad.

The main entrance to the Gothic Cathedral at Amiens, showing the central portal of the west facade, which depicts scenes from 'The Last Judgement.' The Australian Corps saved Amiens and its cathedral from the Germans, when they halted the enemy advance near Villers -Bretonneux, in late late March and April 1918. (Copied from a French postcard.)

My pass was only made out to Ameins Station and not for the town and naturally the military police kept wanting to see my pass. They had to be satisfied by seeing my railway warrant.

At about 9pm I arrived back at Abbeyville quite pleased with myself and I knew that the folks at home would be pleased too that I had the good luck to meet Geo. From Abbeyville I posted 5 or 6 booklets of PCs (postcards) home to Dad. My time was quite enjoyable at Abbeyville and one had a good opportunity to learn.

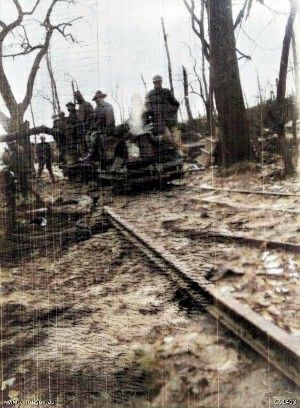

It was on August 2nd 1916 I came back on a cable wagon at dinner time

Soldiers, horses and cable-laying limber of No. 4 Detachment Cable Section, 2nd Divisional Signals Company, 1st AIF, pulled off the side of a road during a temporary halt while travelling in a rural area. Members of the unit are riding either on horseback or on the wagon, which is being pulled by a team of six horses. The Cable Section was responsible for laying telephone cables.

Verner was in No 2 Section 2nd Divisional Signals Company and this photo would be very close to his experience, perhaps even the very equipment he used.

and looked on the board to see who were to go away that day. Anderson, Sanderson, Daniels and Barns are to go to 2nd Div Sig. Co. They will report 1.30pm to orderly room to see equipment is complete. At 5pm we go down to the station and wait there until 10.30pm when our train leaves. I didn't need much rocking that night. We laid down on the seats and awoke next morning still on the move. The distance from Abbeyville is between 30 and 40 kilometers. A good train would make the run in an hour but 24 hours found us at our destination making it now 10.30pm on 3rd. That night we slept out in the open. Somewhere the guns were going their hardest. Flares were going up. Aeroplanes and balloons all gave us the idea there was a war on.

For 1916, Britain and France planned a joint major offensive in the Somme area, but the Germans struck in February with a huge attack on French forts at Verdun. Here, the Germans aimed at nothing less than 'bleeding France white' and bringing Britain, a country which depended on imports by sea to wage war,to her knees by instituting unrestricted submarine warfare.

One hundred and twenty-five miles northwest of Verdun, to the north-east of the town of Albert, the British and French armies joined at the Somme River. British General Douglas Haig ordered a massive bombardment of the German lines that would last a week and could be heard across the Channel in England.

After seven days and nights of massive bombardment in which over one million shells were fired, British General Douglas Haig orders his troops "over the top." Because of the use of this heavy bombardment of German lines, the men were told that they would march with ease into the German trenches where they would find all the Germans dead.

But the German troops were deeply dug in and the bombardment did not reach them.

Once the shelling was over, of the 100,000 British troops who attacked the German lines July 1, 1916, 20,000 were killed and over 40,000 were wounded. It was the single worst day in deaths and casualties in British military history.

Eventually this battle, which did not change the front line trenches much at all, involved over 2 million men along a 30 mile front. British and French losses numbered nearly three-quarters of a million men.

The opening attack failed to achieve a breakthrough, but because of the need to keep supporting France at Verdun, the British pressed on. The AIF was soon pulled into this titanic struggle.

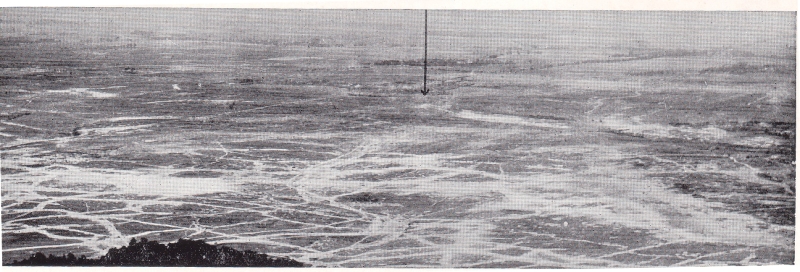

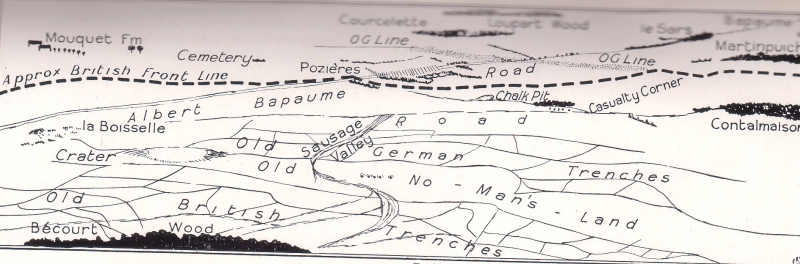

Only too true there was. On the 4th of August we reported to 2nd Div HQ. The OC gave us instructions to go to the 5th Brigade. A motor car was brought around for us. So we four found ourselves going along in style per motor car. And so we traveled until the car could go no further without being observed. Shanks Ponies were to complete the rest of the journey and so we started going through Sausage Gully.

Australian soldiers in 'Sausage Valley' on the road to Pozieres, 1st August 1916. The valley was named 'Sausage' after a German spotter balloon which was flown in the area. The valley on the opposite side was dubbed 'Mash'. As Verner relates it was also known as 'Sausage Gully'. This is a view of the Somme battlefield north towards the village of Contalmaison which is being shelled by the Germans. Australian troops from the I Anzac Corps passed along this route to the fighting at Poziéres and Mouquet Farm between July and September 1916.

There was a continual Bang Bang Bang and retaliation was Whiz Bang shrapnel. High explosives were bursting all around us. We had no steel hats. We were passing wounded going to the dressing station until we came to the 5th Brigade H.Q. which was a cellar. After reporting we looked for dug outs for sleeping. I eventually found one with a sheet of iron and some sand bags on. Was making myself comfortable when bang and poof a shell just landed and dug a dead Fritz up. The smell was anything than a bunch of violets. We reconciled ourselves to the fact that we were at war now and not reading of it and of course these minor details pass unnoticed now.

We were soon put on duty. I was alotted Telephonist duties. It was on account of four or five of Section being Gassed that we came to reinforce. That night they gave our head Quarters a good shelling including a gas shell. Sleep was out of the question as one had to have gas helmets on and off most of the nights. Our boys attacked that night and captured a ridge which was of great importance to us.

Verner found himself landed in the thick of it, towards the final days of the "Battle of Poziéres", a two week struggle for the village and the ridge on which it stands. The first attack was made on the 23rd of July was made before he arrived. The day of his arrival, the 5th of August, was immediately after the 2nd Division, of which he was a part, had relieved the First Division and captured the Pozieres Heights at great cost. On the night of 5th August the Australians were subjected to extreme bombardment. The ground they now occupied could be shelled by the Germans from all directions, including from Thiepval which lay to the rear. This gives us some insight into what he experienced in his first days at the front.

The Battle of Pozieres

The village of Poziéres, on the Albert-Bapaume road, lies atop a ridge approximately in the centre of what was the British sector of the Somme battlefield. Close by the village is the highest point on the battlefield and, while the Somme terrain is only gently undulating, any slight elevation aided observation for artillery.

Poziéres was critical to the German defences; the fortified village formed an outpost to the second defensive trench system which became known to the British as the "Old German Lines" or "O.G. Lines". This German second line extended from beyond Mouquet Farm in the north, ran behind Poziéres to the east then south towards the Bazentin ridge and the villages of Bazentin le Petit and Longueval.

Between 23 July and early September 1916, the 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions between them launched 19 attacks on German positions in and around the ruins of Pozieres. The village was not taken until the 25th of July, and the crest of the ridge not until the 5th of August.

The preparation for the attack involved a thorough bombardment of the village and the O.G. Lines lasting several days.

It was also intended that the O.G. Lines would be captured as far as the road but here the Australians failed, partly due to strong resistance from the German defenders occupying deep dugouts and machine gun nests, and partly due to the confusion of a night attack on featureless terrain. The weeks of bombardment had reduced the ridge to a field of craters and it was virtually impossible to distinguish where a trench line had run.

The failure to take the O.G. Lines made the eastern end of Poziéres vulnerable and so the Australians formed a flank short of their objectives. On the western edge of the village, the Australians captured a German bunker known as "Gibraltar", which was the only structure in the area to endure the bombardment.

The German bombardment intensified on 25 July in preparation for their next counter-attack to retake the village. At its peak, the German bombardment of Poziéres was the equal of anything yet experienced on the Western Front and far surpassed the worst shelling endured by an Australian division thus far. The Australian 1st Division suffered 5,285 casualties on its first tour of Poziéres. On 27 July, the 2nd Division relieved the First Division at Pozieres and captured the Pozieres Heights at great cost.

The Australians suffered 23,000 casualties while advancing two kilometres; British and Australian artillery were no match for German artillery and machine guns. The cost had been enormous and in the words of Australian official historian Charles Bean, the Poziéres ridge is "more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth."

The initial failure of the Second Division to take Pozieres heights was followed by frenzied preparations for a new assault. Communication trenches and front line trenches were dug across this devastated corpse ridden landscape to convey the attacking battalions to jumping off positions east of Pozieres village. This was essential work if men were to be able to approach these positions in comparative safety but it was conducted under continuing heavy German shelling of the whole area.

Digging parties were driven hard. However, all this furious digging allowed the infantry of the Second Division to assemble, virtually undetected by the Germans, at dusk on 4 August 1916. After a three minute intense bombardment the Australians advanced at 9.15 pm to seize OG 1, and OG2 was taken soon afterwards. On the morning of 5 August they could look out from the heights of the Windmill on Pozieres ridge over the German rear line and to the rooftops of the village of Courcellette. It was a virtually unshelled landscape of green fields, a great contrast to the devastated terrain behind them and, in Bean's words, 'it brought encouragement as a view over the promised land'.

By 5 August the brigades of the Australian 2nd Division were exhausted and were to be relieved by the Australian 4th Division. While the relief was underway on the night of 5 August the Australians were subjected to yet another extreme bombardment. The ground they now occupied could be shelled by the Germans from all directions, including from Thiepval which lay to the rear.

On the morning of 6 August a German counter-attack tried to approach the O.G. Lines but was met by machine gun fire and forced to dig in. The bombardment continued through the day, by the end of which most of the 2nd Division had been relieved. From its twelve days in the line, the division had suffered 6,848 casualties.

At 4 am on 7 August, shortly before dawn, the Germans launched their final counter-attack. On a front of 400 yards (370 m) they overran the thinly occupied O.G. Lines. Most of the Australians were sheltering in the old German dugouts and advanced towards Poziéres.

For the Australians, the crisis had arrived. At this moment, Lieutenant Albert Jacka, who had won the Victoria Cross at Gallipoli, emerged from a dugout where he and seven men of his platoon had been isolated, and charged the German line from the rear. His example inspired other Australians scattered across the plateau to join the action and a fierce, hand-to-hand fight developed. Jacka was badly wounded but as support arrived from the flanks, the Australians gained the advantage and most of the surviving Germans were captured. No more attempts to retake Poziéres were made.

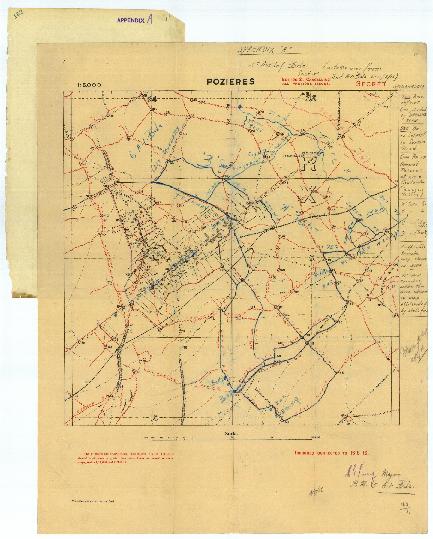

A flyover view of the Pozieres area. Visible is the village (arrowed), the Albert-Bapaume road and Sausage Valley. The O.G. lines are also faintly visible beyond the village (trenches OG1 and OG2).

An aerial view of Pozieres. Click the picture to compare this with the corresponding area of the trench map of the 5th Brigade in August 1916 and a layout diagram of the area.

A map from the 5th Brigade diary August 1916 showing the front line N.E. of Pozieres where they relieved the 2nd Brigade on the 21st of August. Click to enlarge and explore the map.

A documentary account of the battle does nothing to describe the reality that Verner was exposed to. His account is typically understated and we might understand more from the writings of others.

After the First Division captured the Pozieres Heights and the survivors were relieved on 27 July, one observer, Sergeant E.J. Rule said:

"They looked like men who had been in Hell... drawn and haggard and so dazed that they appeared to be walking in a dream and their eyes looked glassy and starey."

Before the attack of 4th August Second Lieutenant John Raws, 23rd Battalion (Victoria), of Adelaide, wrote of what it was like as he and 200 men of the battalion worked on the night of 31 July 1916 to the north east of the village :

Just before daybreak an officer out there, who was hopelessly rattled, ordered us to go. The trench was not finished. I took on myself to insist on the men staying, saying that any man who stopped digging would be shot. We dug on and finished amid a tornado of bursting shells. All the time, mind, the enemy flares were making the whole area almost as light as day. We got away as best we could. I was buried twice, and thrown down several times, buried with dead and dying. The ground was covered with bodies in all stages of decay and mutilation and I would, after struggling free from the earth, pick up a body by me to try and lift him out with me, and find him decayed corpse. I pulled a head off. Was covered with blood. The horror was indescribable.

From Bill Gammage The Broken Years (1974) p 164:

The Second Division relieved the First on 26 July, and gave way to the Fourth Division on 5 August. The incoming battalions were quietened by the ruin they saw: by the dead,'dozens and dozens, all distorted and frozen looks of horror on their faces', and by the storm of shells, which 'became too awful for words, burying men alive and blowing up trenches, and making the whole place a shambles like a huge ploughed field'.

CEW Bean's private accounts of the Pozieres period.

From: Making the legend The war writings of C.E.W. Bean. (Selected by Denis Winter, University of Queensland Press, 1992)

Pozieres has been a terrible sight, suffused with pink and chestnut. One knew that the brigades which went in last night were there today in that insatiable factory of ghastly wounds. The men are simply turned in there as into some ghastly great mincing machine. They have to stay there while shell after shell descends with a shriek close beside them, each one an acute mental torture, each shrieking, tearing crash bringing a promise to each man instantaneous. I will tear you into ghastly wounds, I will rend your flesh and pulp and arm or a leg; fling you half a gaping, quivering man like these that you see smashed round you to lie there rotting and blackening like all the things you saw by the awful roadside. Ten or twenty times a minute, every man in the trench has that instant fear thrust upon his shoulders - I don't care how brave he is - with a crash that is physical pain and strain to withstand.

- Bean, Diary, 4 August 1916 (pp100-101)

Walking across parts of the ground near Pozieres Windmill is like trying to walk across honeycomb. There is barely room between the huge shell-holes for a man to tread. There are three bits of building left in the village - three solitary fragments of wall. The rest is eaten into the ground as if someone has poured acid all over the surface of it.

- Letter, Bean to his parents, 2 October 1916

The dead lay sometimes in batches of ten or twelve together, especially of the 28th. There was not a soul in sight; only the powdered grey earth. No sign of any trenches of ours. All as still and dead and deserted as an ash heap . . . I turned back and followed a goat-track path. There were only blackened dead and occasionally bits of men and torn bits of limbs unrecogrnsably along it. I wandered on for five minutes without seeing a sign of anybody till I came to a gradually improving trench, quite deserted, peopled only by dead men, half buried, some sitting upright with bandaged heads apparently little hurt except for the bandaged wound; others lying half covered in little holes they had scatched in the trench side . . . I didn't want to go through Pozieres again. I have seen it once now.

- Bean, Diary, 31 July 1916

About midnight on the 5th our Brigadier came out. I was not sorry as it was a very hot initiation and not many had a hotter one. Prior to going to the Somme the Aust were up North and it was quiet then and they got gradually broken in to the shell fire. We arrived at Tara Hill in the wee hours of the 6th.

![Tara Hill, 1917. [AWM P01835.038]](images\\Tara_Hill-X2_E-ColorizedR.jpg)

Tara Hill, France, 1917, near the Becourt Wood not far from Albert. A tree trunk that served as an observation post on the hill located northeast of Albert. An Australian officer, possibly from the 2nd Divisional Signals Company, 1st AIF, is climbing the steps which have been driven into the trunk. Away to the northeast in the background is Black Watch Alley or Gully.

Tara Hill is not a local place name but one given by certain battalions of the Northumberland Fusiliers, known as the 'Tyneside Irish', to the hill which rises just east of Albert. (Tara is the famous hill in County Meath where the High Kings of Ireland reigned in ancient times. It features in much Irish mythology, poetry and folklore. On 1 July 1916, the Tyneside Irish had advanced towards the Germans down the opposite side of the hill from Albert from positions they had christened the 'Tara Usna Line'.)

About midday General Birdwood addressed us and we marched off via Albert to Warloy and needless to say was glad to be back a bit.

About midday General Birdwood addressed us and we marched off via Albert to Warloy and needless to say was glad to be back a bit.

Click here to explore a map of the Albert area. Here you will find Warloy to the West and Pozieres to the North East as well as many of the towns and villages he refers to : Senlis, Vadencourt, Becordel, Fricourt and Ribemont. La Vicogne and Pernors are to the North of Amiens off the map to the West. Scroll down to the overview map and locate Pozieres and Amiens to get an idea of the locations.

On the 8th we packed up and marched off to LAVICOGNE. It was a 12 mile march and very hot too. Next day on the march again to PERNORS. This was another hot march. We enjoyed our few days at PERNORS.

On the 8th we packed up and marched off to LAVICOGNE. It was a 12 mile march and very hot too. Next day on the march again to PERNORS. This was another hot march. We enjoyed our few days at PERNORS.

La Vicogne is a commune in the Somme, situated some 12 miles north of Amiens, on the N25 road. Vadencourt is Situated some 10 miles northeast of Amiens, on the D919 road.

On the 16th we again were on the march to LAVICOGNE. Next day 17th on the march again. We arrive at VADENCOURT full kit and rapid march no fun this weather. The 20th arrived and away we go again on the march arriving at ALBERT. Heavy bombardment going on. We leave ALBERT about 8-30p arriving at SAUSAGE GULLY 10pm. We stayed there that night in a big dug out what was once a Fritz.

On the 16th we again were on the march to LAVICOGNE. Next day 17th on the march again. We arrive at VADENCOURT full kit and rapid march no fun this weather. The 20th arrived and away we go again on the march arriving at ALBERT. Heavy bombardment going on. We leave ALBERT about 8-30p arriving at SAUSAGE GULLY 10pm. We stayed there that night in a big dug out what was once a Fritz.

On the 23rd we proceed further up to our advance Brigade HQ. Pretty lively time reaching there too. During the night he kept up a continual bombardment up. The linesmen were kept busy all night mending wires.

On the 23rd we proceed further up to our advance Brigade HQ. Pretty lively time reaching there too. During the night he kept up a continual bombardment up. The linesmen were kept busy all night mending wires.

24th still subject to shelling including four hours gas shelling. Very unpleasant having to sit and wear helmets. I fell off to sleep with mine on in the dugout. We had a pretty rough time in shelling. Thanks to one of Fritz's deep dug outs it stopped shrapnel and H.E.

24th still subject to shelling including four hours gas shelling. Very unpleasant having to sit and wear helmets. I fell off to sleep with mine on in the dugout. We had a pretty rough time in shelling. Thanks to one of Fritz's deep dug outs it stopped shrapnel and H.E.

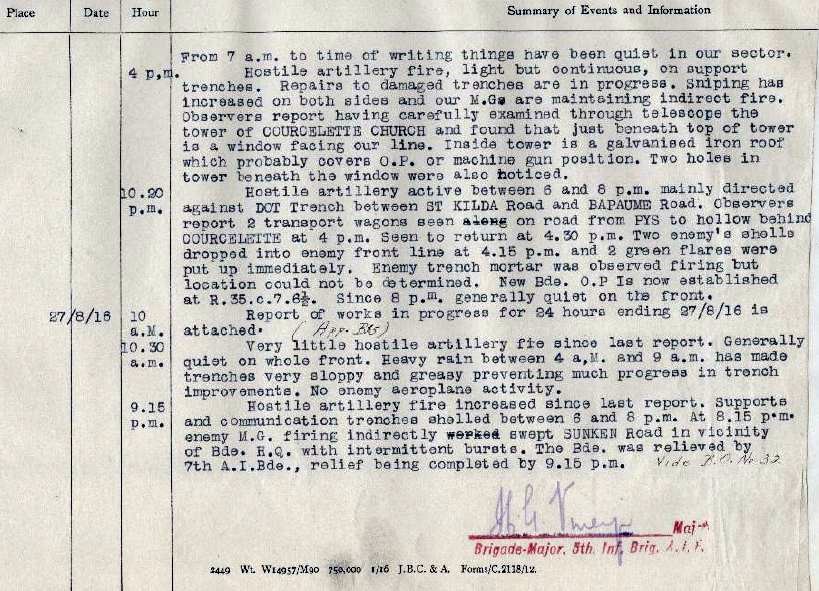

It was on the 27th when the 7th Bde relieved us and at 6.30pm we made a start to go out.

The Fritz made a start too by shelling so we stayed for a while until he cooled down a bit. However we arrived at

Brick field about 8.30p tired. On duty 12 midnight to 4 am. Very cold in the dug out.

It was on the 27th when the 7th Bde relieved us and at 6.30pm we made a start to go out.

The Fritz made a start too by shelling so we stayed for a while until he cooled down a bit. However we arrived at

Brick field about 8.30p tired. On duty 12 midnight to 4 am. Very cold in the dug out.

28th went into ALBERT Fritz bombarding all day. HE and shrapnel on roads. Balloons and planes busy.

28th went into ALBERT Fritz bombarding all day. HE and shrapnel on roads. Balloons and planes busy.

In the dug outs I was sleeping rats and frogs were also sharing it. At 8.30am moved off again arriving at WARLOY sometime during same day. On the 31st General Birdwood addressed us and presented decorations to some. At 1.15pm on same day we marched off for BEAUVAL a 15 miles march on a hot day with full pack. We arrived at BEAUVAL at 7.45pm needless to say very tired. Spr. Daniels took ill during night and taken to hospital where he died during out stay at Beauval.

On Sept 4th or rather the 5th at 2.30 a.m. we awoke and left BEAUVAL at 3.30am for DOULLEENS arrived at 5am entrained and left at 6.20am arriving at a siding called Hopoal or some such name. However we hopped out and marched to POPERINGHE very miserable day.

On Sept 4th or rather the 5th at 2.30 a.m. we awoke and left BEAUVAL at 3.30am for DOULLEENS arrived at 5am entrained and left at 6.20am arriving at a siding called Hopoal or some such name. However we hopped out and marched to POPERINGHE very miserable day.

Poperinghe is an ancient Belgian town situated south of the province of West Flanders, Poperinghe was the primary military centre for British forces located in Flanders, just under 10km west of Ypres.

The 1st Australian Division reached Poperinghe - six miles short of Ypres-on August 28th, the 3rd Brigade being for a few days billetted in that town and the 2nd in camps of huts and tents in the neighbourhood.

Verner was in the 5th Brigade of the 2nd Division and was also billetted at Poperinghe which gives us some idea of the numbers of men on the march and in billets in the area.

Went down the street. Was having a feed of chip potatoes and eggs when bang. bang. Fritz put a couple of long range shells over. The women folk got down the cellar and shut up their shops. I found myself outside and the civilians running all ways. It caused some amusement amongst us boys as the shells fell a considerable distance from the town. On the 6th I met Harry Norrish, Had a good yarn. POPERINGHE was a nice large town. Enjoyed ourselves there, The flemish folk appear very nice and mostly talk a little English.

On the 9th at 9.30pm left POPERINGHE for EPYRES per train. Arrived at 9.30 am detrained and march to our Bde HQ reaching there at 10.15am. Very comfortable HQ in Ramparts. On duty midnight to 4am.

On the 9th at 9.30pm left POPERINGHE for EPYRES per train. Arrived at 9.30 am detrained and march to our Bde HQ reaching there at 10.15am. Very comfortable HQ in Ramparts. On duty midnight to 4am.

We stayed at EPYRES until the 6th October. I won't dwell on each days routine but it was a lovely HQ. Best we have had. Our position was in a Salient and of course the enemy had a good view from the hill so to walk about during the day it was not the safest.

Verner is referring to the Ypres Salient. A "salient" is a bulge in the front line which juts into enemy territory, making it particularly vulnerable.

The operations carried out during this term at Ypres were unimportant, consisting chiefly of three series of raids undertaken by the divisions there, as by all others holding quiet parts of the British front, in order to occupy the enemy's attention during the Somme offensives of September Ist, 25th, 26th, and October 12th. In reality the main task of this period was the improvement of the defences of the Salient, which-having till then been systematically blown down whenever an attempt was made to repair them appeared dangerously weak. At the end of August and beginning of September the force was withdrawn from the charnel-house of the Somme to take over from the Canadians the southern half of the Ypres salient. In normal times the Salient had been by far the most difficult and dangerous sector of the British front.

I visited the ruins of Ypres. It is a large town but simply ruined now by shell fire.

Click here to explore a map of the Ypres area. Scroll down to see an overview map and its position relative to Bullecourt, Bapaume and Pozieres.

Ypres presented a tragic picture of devastation and one with the desolation of its great battlefields at Zonnebeke, Broodseinde and Passchendaele. Of its magnificent Cloth Hall and Cathedral, only the gaunt skeletons remained.

Aeroplanes were very busy on this sector and we often witness air duells. Shelling was intermittent. Weather was of a variable nature. Plenty of rain during our stay there.

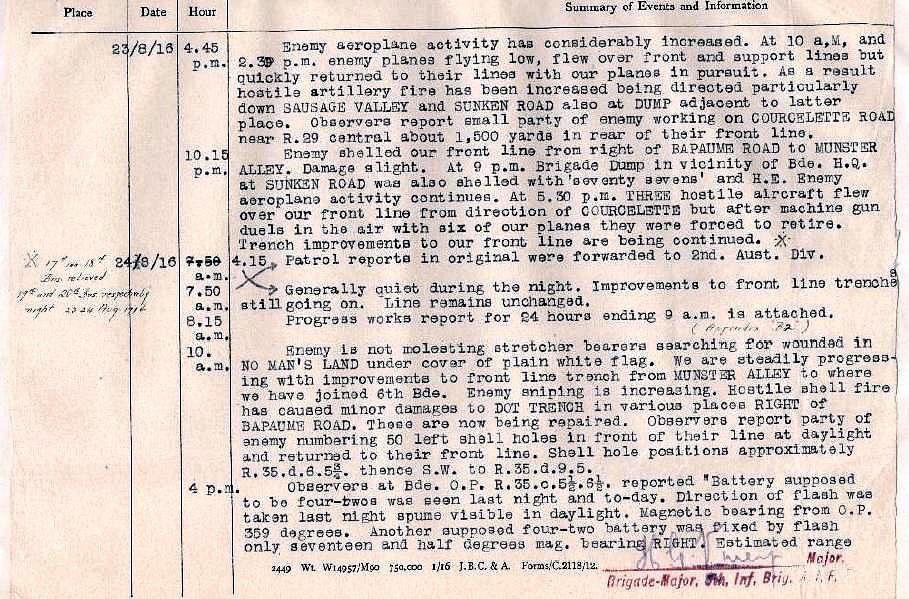

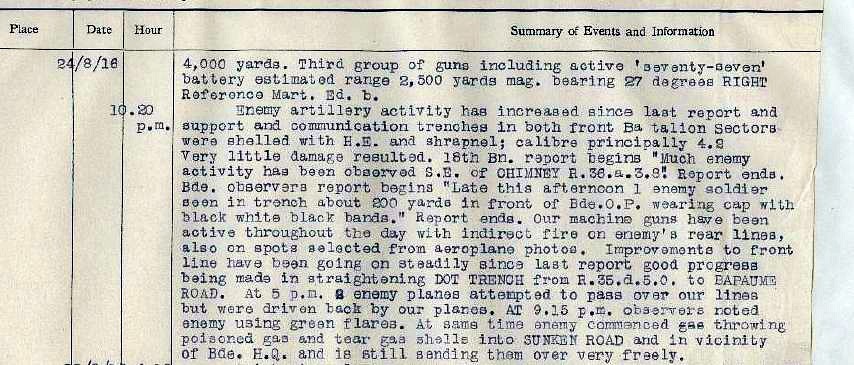

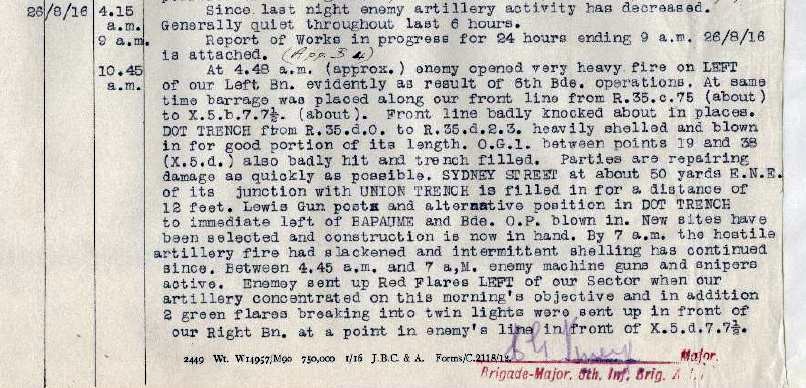

Verner's account of this time is understated and it is worth reading the daily activity details in the Brigade diary for September.

On the 6th of October at about midnight we left Ypres entrained 1am arrived some siding or other too dark to see the name. However our legs were once more on the march and we arrive at STEENVOORDE tired and sleepy. This town quiet and of nothing important.

On the 6th of October at about midnight we left Ypres entrained 1am arrived some siding or other too dark to see the name. However our legs were once more on the march and we arrive at STEENVOORDE tired and sleepy. This town quiet and of nothing important.

from October 12th, except for certain limited attacks to be undertaken, Haig's immediate intention was that his two armies on the Somme should go into winter quarters. For winter fighting and training, both of them were to be organised in a number of quasi-permanent army corps, each of four divisions. Of the divisions in each corps, two would hold the line and attack when feasible, one, billeted in villages just clear of the battlefield, would lie in reserve training and working, and the fourth would train in a back area. The I Anzac Corps (now of four divisions) would take the place of the XV, the central army corps of the Fourth Army, which would be sent back to a training area.

We stayed there until the 12th October when on that day we are on the march again with full pack. Arriving at POPERINGHE 1.30pm only to leave there again on the 15th October for RENINGHELST. Plenty of rats in that vicinity. Wrote letter on the following day. Next day 17th move to the right in forth form fours and right quick march and away we go again back to STEENVOORDE tired of course.

The period from the 12th to the end of October was a series of marches where the 5th Brigade was moved under orders.

The period from the 12th to the end of October was a series of marches where the 5th Brigade was moved under orders.

However we awoke next morning packed up and marched off again for a long pad bad weather rainy and cold. We arrive at ARNEKE only a small village. On our march to this hill a Castle looked pretty right on top of a hill on the right of the road we were marching on. Visited the Church there built 307 years ago.

From the history of the 21st Battalion we find that the "long pad" was 21 1/2 miles. The village of Arneke is approximately 50 kilometres south-east of Calais and about 8 kilometres north-west of the town of Cassel. It is the site of the "Arneke British Cemetary."

The 20th inst we voted in reference to conscription in Australia.

It was at this juncture, on their way from Ypres and Armentihres to the Sommes that the Australian troops were called on to vote upon the referendum concerning conscription. The date for the poll in Australia was to be October 28th, and - probably in the hope that they would give a lead to Australia - the soldiers at the front were to vote earlier. Voting in France was to begin on Monday, October 16th.

On the 21st we were on the march again and quite a long one too. We arrive at NORDAUSQUES about 6pm. I had a lovely blister on my feet however it didn't beat me. I stuck to the march until about quarter of a mile from the village then could not bear it so came along at my own time.

The night (October 2Ist) was dry but bitterly cold, and the men could warm themselves only by digging the mud from their trenches and cutting fire-steps.

Received a letter from Olive then cheered me up somewhat. The village was not of any importance. Posted Xmas cards home and visited field ambulance and had heel bandaged.

![An advance dressing station of the main Vaulx Bullecourt road, 1917. [AWM E00591]](images\\awm-e00591_E-ColorizedR.jpg)

On the 24th we were on the move again entrained at Port REMNEY at 3.40 pm via CALAIS and BOULONGE. Too dark to see those places as I would of liked to. At midnight I found we arrived at BALLANCOURT and soon made my bed on the nice cold floor made from concrete. This village was only a small one about 6 kilos from Abbeyville. The weather was very cold and bleak. No fun at all. On the 26th at 6am we had breakfast ready to march a few kilos to continue our trip via PICQUENCY and AMIENS per motor transport arriving at PIREMONT about 10pm same night. A very cold ride it was too. It was needless to guess that we were back to go on to the "Somme" front again.

Because of the losses the Australians had sustained on the Somme it came as a shock to them to learn that they were to go back there in mid-October 1916. The move was very unpopular. One onlooker who observed Australians leaving Flanders on 12 October 1916 noted how grim the men looked 'without the least buoyancy about them'. There could be no question that the second move to the Somme was highly unpopular. While some units felt it more than others, few of them came out of the line at Ypres with their usual spirits.

On the 28th I was busy looking for these beastly "Chats" in my shirt when who should come in my elaborate billet built to keep the French cows in on peace times. Never mind it was a covering and that wasn't too bad as long as the floor was dry.

Lice infestation was the norm in the trenches - it is estimated that up to 97% of officers and men who worked and lived in the trenches were afflicted with lice. It was decidedly a trench phenomenon. Lice were also commonly referred to as 'chats'. Men would gather in groups to de-louse themselves (i.e. 'to chat').

Yes as I mentioned who should come in but "George" my Bro. and needless to say I was so pleased to see him. So I wasn't on duty we went for a walk together and had a few cups of coffee at a "Cafe" and a good yarn.

The next day I paid him a visit at Hailly where he was billeted. After having a piece of toast and a cup of tea I had to go back as the weather was looking very unsettled. He walked down the road with me for some distance and we said farewell again and so time went on with very cold and wet weather.

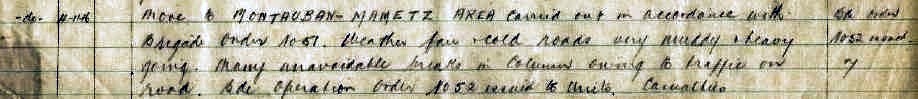

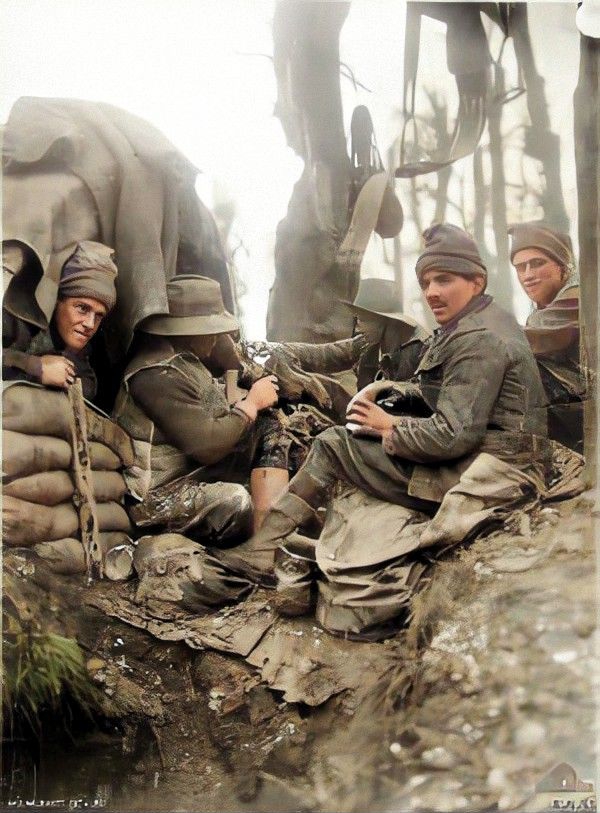

November 4th arrived and we form fours and march off again with packs up and it was some march too not to be forgotten too soon. The mud was terrible bogged up to the knees all over the place.

November 4th arrived and we form fours and march off again with packs up and it was some march too not to be forgotten too soon. The mud was terrible bogged up to the knees all over the place.

Extract from the history of the 21st Battalion : From Buire on the 3rd November we pushed out into the sea of mud which was the Somme battlefield of a month before. The rains during the previous month had made conditions indescribable. The photographs published give no idea of the sodden, cheerless and filthy trenches and shell holes in which the British army on the Somme fought and worked in the winter of 1916-17. Neither have we space in this short account to describe the battle with the mud in any detail.

When considering the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, what immediately springs to mind is a desolate, shattered landscape of mud. ... this was a lengthy campaign (July to November), and the weather conditions proved quite changeable and fickle. The other factor at Ypres was the physical characteristics of this part of Flanders. The water table in this area is very high and indeed parts of the battlefield were swamp or reclaimed swamp. So even when the surface appeared dry, it could in places be sodden below the crust and digging into the ground even to a shallow depth would invite water. Naturally the blanket coverage of shell craters only made the situation worse.

We arrive at MONTAUBAN. What was once a village but not a sign of a building can one see now not even a brick.

Martinpuich, Albert-Bapaume area, France, 1917. Squatting amidst the ruins of the village located southwest of Bapaume, a linesman with the 2nd Divisional Signals Company, 1st AIF, works on a communications cable.

Parts of the Somme area were completely erased by shell-fire. Strangers who visited the battlefields during the following years were much impressed by the ruins of Le Sars and Flers, of which the wreckage could be seen, but for many villages no ruins above-ground remained - not even enough for mending the roads, which was the fate of most of the Somme villages. Some places had become an open moorland, and the visitor passed through without suspecting that a village had ever existed there.

On the 6th it was another move closer to Fritz this time and the march in the mud before we reached our HQ was no fun besides dodging shells and shrapnel. Our HQ was in the valley of death.

On the 6th it was another move closer to Fritz this time and the march in the mud before we reached our HQ was no fun besides dodging shells and shrapnel. Our HQ was in the valley of death.

I have not been able to find where the "Valley of Death" was, but from these accounts it must have been somewhere in the region of Montauban E1 and Flers D2 which you can find on the map here.

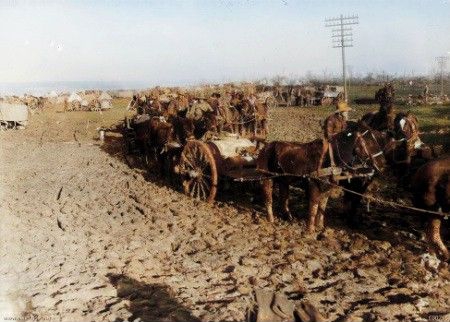

Australian transport lines making their way through the mud between Mametz and Montauban, 6 November 1916

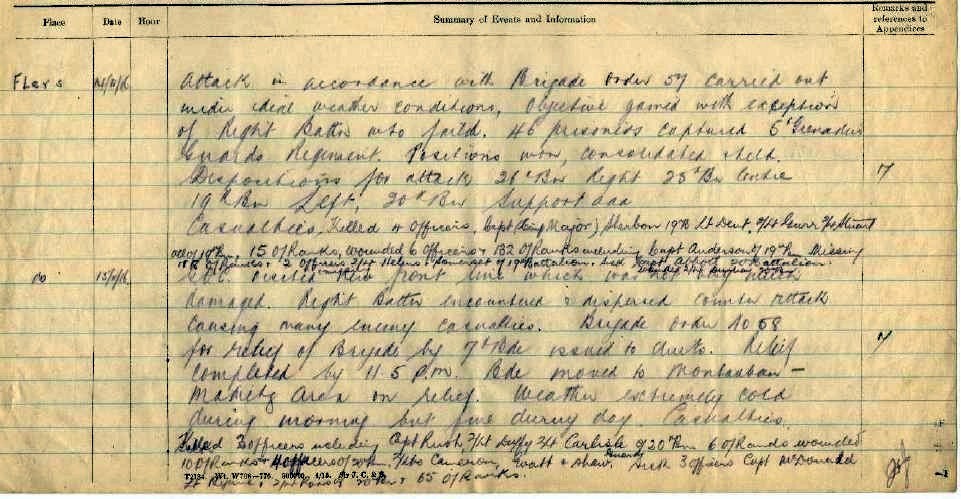

Two of the three battalions of the 7th Brigade responsible for the Australian share in the operation had taken over the front line on the night of November 3rd; of the others, the 25th. which was to form the centre, and the 26th - the reserve - were to have moved up from Carlton Trench, Longueval, on the night of November 4th.

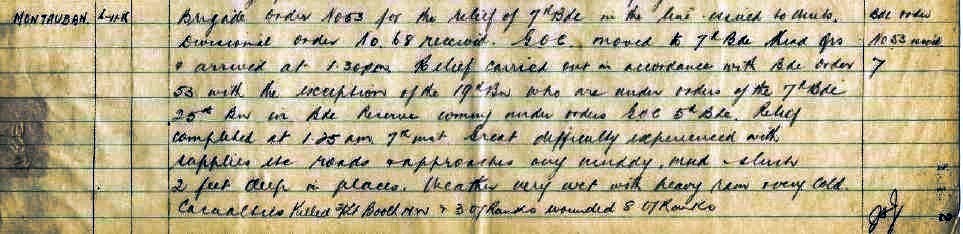

We relieved the 7th Bde who made an attack, but were not too successful.

We relieved the 7th Bde who made an attack, but were not too successful.

On 5 November 1916, the Australians launched one attack near Gueudecourt before dawn and another near Flers in mid-morning. A further attack was made near Flers on the 14th. These actions were made in some of the worst conditions the Australians were to experience on the Western Front. These attacks were carried out by two battalions of the First Division. The battalion at Gueudecourt, after an exhausting journey through the mud, was seen and shelled and was unable to assemble in no-man's-land. The troops advanced in good order but because of the poor conditions they could not keep pace with the creeping barrage. Similar conditions existed at Flers later in the day and, while troops from both assaulting forces held parts of the enemy trenches for some hours, the partial gains were not defensible and the Australians withdrew.

November 7th was a day of drenching rain and wild gale, and - partly in consequence of the concentration of energy upon works needed for the next attack - the conditions became so appalling that this operation, at first fixed for the 7th, was eventually postponed until the 14th.

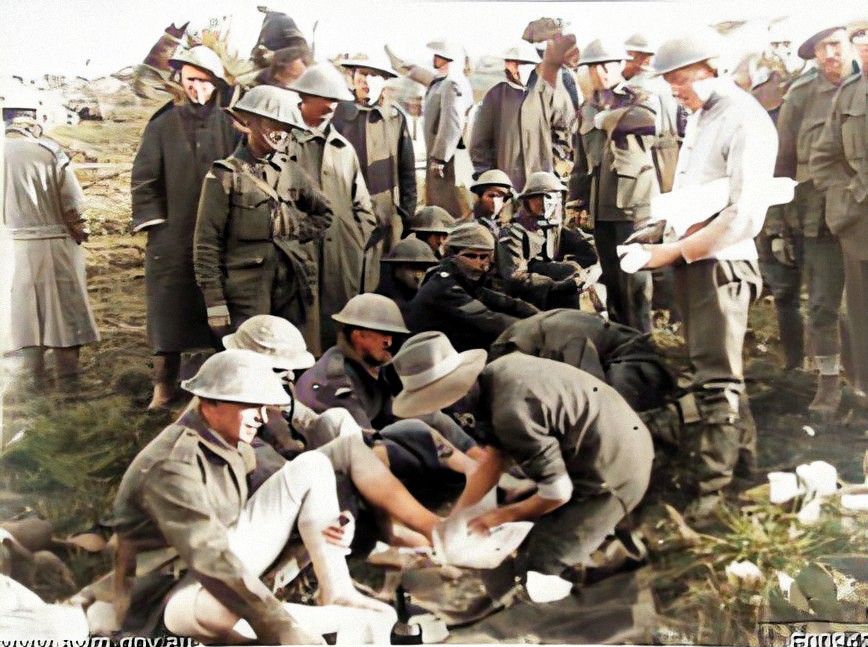

On our arrival the stretcher bearers were busy carrying wounded. There were many evacuated with trench feet too. The trenches were terribly full of muck and impossible to have dry feet.

In all British divisions subjected to them since the middle of October these conditions had resulted in the occurrence of the form of frost-bite commonly known as "trench feet". This trouble, resulting from local stoppage of circulation, and too often ending in gangrene and the actual loss of the foot, could be prevented by discarding the tightly-wound puttees and wrapping loose sandbags instead around the shins, wearing loose boots unlaced at the top and regularly taking them off and rubbing the feet with whale-oil, drying feet and boots in specially provided drying-places, putting on dry socks, and maintaining the body with one hot meal daily and an occasional drink of hot coffee or cocoa.

After a tour in the line during this continued wet-weather offensive, practically all the men in many Australian battalions were suffering from " trench feet," at least in its incipient stages. Thus, when the 27th Battalion (7th Brigade) was relieved after the fight of November 5th, ninety per cent. of its men were said to be affected. In the 5th Brigade (which relieved the 7th) the 17th Battalion, coming out of the line 498 strong on the night of November 7th, sent to hospital an officer and 150 men, mostly with trench feet, and reported that 140 others would be unfit for duty for several days. Its sister battalion, the 18th, reported 4 officers and 132 men sent to hospital, and another 100 unfit for duty.

Extract from the history of the 21st Battalion : During this period we had our first introduction to gum boots and "trench foot". The gumboots became battalion stores on moving into the line and many arguments occurred when it came to claiming one's own leather boots when we moved out. "Trench Foot" is an ailment caused by the combined effects of cold, wet, and dirt and results in a swelling of the feet, which is very painful and some times necessitates amputation. Various antidotes such as rubbing and bathing the feet were instituted with good results, but "trench foot" was no means eliminated.

On the 14th our Bde charged and gained their objective. Fairly heavy losses captured prisoners two of our linesmen were wounded and one killed. The shelling was very heavy. Our food was scarce and tea made of dirty shell hole water. Did not give it a good flavor. It was absolutely one of the worst positions I have been in as far as food and sleep and comfort is concerned. On the 15th we went back in reserve and for those ten days it is hard to forget. We had practically no sleep during our time at FLERS or VALLEY of DEATH.

On the 14th our Bde charged and gained their objective. Fairly heavy losses captured prisoners two of our linesmen were wounded and one killed. The shelling was very heavy. Our food was scarce and tea made of dirty shell hole water. Did not give it a good flavor. It was absolutely one of the worst positions I have been in as far as food and sleep and comfort is concerned. On the 15th we went back in reserve and for those ten days it is hard to forget. We had practically no sleep during our time at FLERS or VALLEY of DEATH.

The attacks of November 4th-5th and 14th and the interval between them formed the most trying period ever experienced by the A.I.F. on any front. On his journey into the trenches, each infantryman now carried his greatcoat, waterproof sheet, one blanket, 220 rounds of ammunition, and, when fighting was in prospect, two bombs, two sandbags and two days' reserve rations, besides the remnant of that day's "issue".

Thus burdened, the troops dragged their way along the sledge-tracks beside the communication trenches, the latter - except in the actual front system being now never used. But the sledge-tracks also were by this time deep thick mud, which, especially when drying, tugged like glue at the boot-soles, so that the mere journey to the line left men and even pack-animals utterly exhausted. In the dark those who stepped away from the road fell again and again into shell-holes; many pack-animals became fast in the mud and had to he shot, and men were continually pulled out, often leaving their boots and sometimes their trousers.

After each fight, when the carriage of wounded across this area had to be performed almost entirely by stretcher-bearer, these men, working in four or five relays of six or eight to each stretcher, were quickly worn out ; and, though detachments of the 21st and 24th Battalions worked devotedly as well as all the available bearers of the field ambulances, numbers of wounded, after being tended at the forward aid-posts, had to be left lying for twelve hours in the open without blankets for want of men to carry them. When sledges became available, single horses were often unable to drag them. A man of the 27th has recorded that when, after lying in No-Man's-Land for five days with a smashed leg, he was eventually brought to the trenches by stretcher-bearers under a white flag, he had to be dragged thence over the mud area by three horses attached to a sledge.

Coming into the trenches under such conditions, and starting their tour of duty in a state of exhaustion, the garrison of the front line usually had to stay there forty-eight hours before relief. At first the men tried to shelter themselves from rain by cutting niches in the trench-walls, but this practice was forbidden, several soldiers having been smothered through the slipping in of the sodden earth-roof, and the trenches broken down. If, to keep themselves warm, men stamped or moved about, the floor of the trench turned to thin mud. At night the officers sometimes walked up and down in the open and encouraged their men to do the same, chancing the snipers; but for the many there was no alternative but to stand almost still, freezing, night and day. Captain Morgan Jones has recorded that he saw one of the 20th Battalion standing with his feet deep in the mud, his back against the trench-wall, shaken by shivering-fits from head to foot, but fast asleep.

Mud and mud (says the diary of the 18th Battalion on November 8). Men cannot stand still long in one place without sinking up to their knees. Rations arrived, but it was only with great difficulty they could be carried up. No fires were allowed in the front line, and at this stage no food or drink could arrive there hot except occasionally tea, which was carried in petrol-tins and reeked so strongly of gasoline that men declared after drinking it they dared not light a cigarette.

Lorries and even ambulances took twelve hours to make a circuit of a few miles; the actual supply of food to the troops became precarious; and the staffs of Corps and Army found themselves faced by the imminent probability that all motor-traffic on roads to the active front would come to a complete standstill.

On the 18th we left MONTAUBAN and went back to our same position relieved the 7th Bde. They lost the ground we won and our Bde had to regain it.

On the 18th we left MONTAUBAN and went back to our same position relieved the 7th Bde. They lost the ground we won and our Bde had to regain it.

About 11.30pm on the 21st we were relieved by the 2nd Bde of English forces and terrible dark night we had to go out bogging all the way. However we found ourselves at Carlton trench wet through laid down in a bit of a shelter and went to sleep very tired and miserable.

M'Cay's headquarters were at Longueval "Carlton Trench".

About 11.30pm on the 21st we were relieved by the 2nd Bde of English forces and terrible dark night we had to go out bogging all the way. However we found ourselves at Carlton trench wet through laid down in a bit of a shelter and went to sleep very tired and miserable.

M'Cay's headquarters were at Longueval "Carlton Trench".

On 18 November 1916, the Battle of the Somme officially ended and for the remainder of the winter of 1916/17 the Australians garrisoned the line east of Flers. From there they kept pressure on the Germans by means of small attacks and raids. However, the main battle was against mud, rain and frost-bite. The autumn rains had set in by the time the Australians reached the Somme and the whole battlefield had become a sea of mud. Broken ground, easily traversed in dry weather, was a bog. Trenches and tracks were often impassable. It could take relays of stretcher-bearers many hours to bring in a wounded man, the mud slowing the journey to a kilometre an hour. The front lines were up to twelve kilometres away from good roads so major efforts were made to repair approach roads to allow supplies to be brought forward. As the roads neared the front they became 'duckboard tracks', the only surface by which it was possible to get across the sea of mud. Supplies of hot food, leather waistcoats, thigh boots, worsted gloves, dry socks gradually reached the front where they made the awful conditions if not better at least bearable. In the rear, however, both the accommodation and comfort for troops in reserve were dramatically improved.

Awoke at 6am next morning to proceed a few kilos and entrained and proceeded to the other side of ALBERT and then marched about five miles arriving at RIBEMONT about 1pm had dinner and scraped some mud off our clothes.

Awoke at 6am next morning to proceed a few kilos and entrained and proceeded to the other side of ALBERT and then marched about five miles arriving at RIBEMONT about 1pm had dinner and scraped some mud off our clothes.

We were at Ribemont until the 30th and during our time there the weather was miserable and cold. We wrote letters and received letters however on the 30th we were once again on the move. The roads were fairly good for marching. We arrive at RAINNEVILLE about 5pm. I met Harry Norrish. His Bde the 3rd marched out and we took their places.

We were at Ribemont until the 30th and during our time there the weather was miserable and cold. We wrote letters and received letters however on the 30th we were once again on the move. The roads were fairly good for marching. We arrive at RAINNEVILLE about 5pm. I met Harry Norrish. His Bde the 3rd marched out and we took their places.

On 1st Sunday in advent on Dec 3rd I with others proceeded on bikes to AMIENS. After a fall in the street of Amiens one of the wheels of my bike got caught in the tramline and the consequence the bike refused to go and I had to pick myself up from the ground. I left my bike or at least it was mine while I had it, at YMCA. After looking over the town I got my bike about 4.30p and proceeded on my homeward journey.

I took the PERONNE road to go back and all was going well until when I was going down a hill. The bike didn't need any pushing down the hill in fact it was going too fast for my liking I went to put the break on but it did not act and the next thing I knew I found the bike on top of me. I picked myself up with the loss of some skin and the gainer of some bruises. I was too sore to get on the bike again so lead it back to RAINNEVILLE to the amusement of all the boys. I might say that is the last ride I have had on a bike I am not all that friendly with free wheeled bikes now.

We were at Rainneville until the 17th Dec it was only a small village. The billet we were at the old "Damme" used to come and count the rafters in the shed we occupied in case we burnt any.

The battalions were either billeted in the overcrowded, verminous, leaky barns of Buire, Ribemont, and Dernancourt, or forthwith marched on through dense traffic eight or ten miles farther to the "staging camps" on the old battlefield, from which they could be moved within twelve hours to the front line. In the XV Corps area these I "camps" lay about Fricourt, Mametz, and Montauban - once villages but now marked only by some of their visible foundations and in the case of Montauban, by part of the iron-work gate of the churchyard and a Madonna and Child standing in the ruins. Here, as no cover was available for three quarters of the men, the majority slept in the open, improvising what shelter they could with their blankets and water-proof sheets.

On the 17th we were on the march again from 9.30am arriving at DURANCOURT sometime during the afternoon. On the 19th we were on the march again to the once was village of FRICOURT but no sign of any village now. On the 20th left FRICOURT and arrived at MONTAUBAN very cold camp not quite so muddy. On 22nd we left MONTAUBAN at 8am arriving at our HQ at Sun Valley about 1/2 mile from DELVILLEWOOD.

DELVILLEWOOD readers you remember was where the Africians showed the huns what they could do and one could see that it must have been a big struggle to gain this position.

On July 15 at dawn the South African regiment went in following a heavy artillery battle: they managed to clear the southern edge of German forces. The remainder of the wood remained in German hands. Hand to hand fighting ensued until the South Africans were relieved on the night of July 19, having lost 766 dead among the four battalions alone; the dead outnumbered the wounded by four to one. Throughout poor weather (it rained often) and enemy artillery fire which reached a crescendo of 400 shells a minute, the surrounding landscape was transformed into a mess of broken, stumpy tree roots and massive shell holes. Mud and rainwater covered bodies of South African and German forces alike - many bodies remain in the wood today (which is now in private hands). The Germans lost 9,500 men by August alone. The wood was never entirely taken by the South African forces, despite huge efforts to do so. It wasn't until after another month of fierce fighting had taken place, on August 25, that 14th (Light) Division finally took the wood and overcame German resistance. Delville Wood remained the most costly action the South African Brigade fought on the Western Front.

Click here for a diary account of Delvillewood by Captain S. J. Worsley, D.S.O., M.C., 1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment. You can find Delvillewood on this map at E2 (shown as the "South African National Memorial") near Longueval.

It was a sight I do not care to witness to see the bodies laying as they fell of the enemy and those who died gaining this position.

We relieved the 14th Bde here 24th Xmas eve. I received a nice letter from Miss Pollock. Some of the boys receiving parcels. Our batteries sending Fritz Xmas greetings.

25th Xmas day went to communion service held in a dug out. Bacon and bread for breakfast. Dinner stew flavoured of curry, tea bread and jam. Weather cold and showers intermittent shelling also. Xmas day ended with loving thoughts of home.

And so the days pass away all of which are of the same routine. It was very cold not at all like our dear Aust weather at Xmas time. 31st Dec arrived and on that day I was lucky I received 3 parcels altogether and needless to say we lived like KINGS for a while.

I had to go on duty at midnight so I naturally see the old year out and the new year in. Our batteries opened out and gave the HUN new year greetings of course. He returned some of his in exchange and thus the leap year of 1916 ends to the writer in a dug out somewhere in France and escaped all the fair sex proposals.

On the verge of the new year, Australian Corporal Robert Addison wrote: This is the last day of the year, and may the New Year bring the end of this terrible war, and so end so much suffering and bring Peace and Happiness all over the world. Though many undoubtedly shared his view, there were still many fresh Australian recruits eager to enter into battle, with a feeling that their efforts could win the war.

A happy new year to you and such were our greetings to each other. I received a cake in one of my parcels and it was appreciated too. We were not being over fed during this period in the line the roads were so bad and transport was very difficult.

On the 2nd Jany I received another parcel of tobacco cigars from Miss Sharp and it was very welcome too. On the 3rd Enemy was shelling fairly heavily all day. It was on Jany 4th I meet my friend NORMAN LEVICK. We had a good yarn as we both got a surprise to see each other. He came to my dug out to get a drop of water to wash his dixie. A "Dixie" (from the Hindi degci) was an army cooking pot.

Jany 5th a year since I left Australia. It was a much finer day for observation. The planes were busy too and the days pass until the 8th arrives when Sapper Sims and myself were detailed to go to FRICOURT power buzzer school and so we proceed with full packs up to march arriving about 6 pm very miserable and tired.

Click here for details of the "power buzzer" equipment he is referring to as well as links to further information on Signallers and the methods and equipment they used.

I was feeling off color during my time there. I was off color I had no appetite and our sleeping quarters were very cold and sloppy and on the 12th we leave FRICOURT and go back to our unit and what a time we had too walking through the snow looking for our Bde HQ.

On January 14th the wet weather which had prevailed since October gave way to bitter frosts, followed on the 17th by a heavy fall of snow, which lay frozen on the ground for exactly a month. The four weeks of colder and brighter weather from mid-January to mid-February 1917 froze the land and water hard and improved conditions although new troubles arrived. Bread could not be cut with a knife, hands were frozen numb within seconds if exposed, boiling tea quickly became ice, and German shells, no longer cushioned by the mud, exploded with more deadly effect. This 'Somme Winter' experience was not easily forgotten by men who served through it. One historian of the AIF has described the mood engendered by the terrible losses of the Somme battles and the trials of the winter"

We found it at last in reserve. HQ were in a terribly deep dug out supposed to have been the Crown Princes H.Q. It was certainly a very elaborate dug out.

I wasn't feeling all that well. Some shell hole water evidently didn't agree with me. On the 12th I went and seen the Dr of the 12th field ambulance. Snowing very heavily all day. I slept there that night. Next day I was sent down to BECORDEL after going through a lot of red tape and I finally got down to BELGUE FARM near ALBERT and slept in a hut for that night. The Dr visited others and myself in the morning of the 18th. Went to bed again put on light diet. Weather terribly cold. On the 21st I got up for a while on the 22nd left the ward and went to convalescent. I remained in convalescent until the 28th of Jany. Ok and wasn't cold.

January weather was fog, frost, snow and very cold with many of the men sick. Also several men were wounded or killed. The Brigade diary for January makes interesting reading.

I left convalescent camp and marched to DURANCOURT and joined my Bde again and received several letters from home and friends. Next day left DURANCOURT for ALBERT. During the night Fritz dropped a few bombs over the town. On the 31st we left ALBERT for SHELTER WOOD. Why it was called Shelter Wood I don't know. No shelter and no wood. Probably before the war it was as it name suggests.

Feby 1st up at 6am breakfast 6.30am. Quick march 7.30am roads very slippery being frozen. Every two paces forward you would slip back one. We are at Villa Siding (pretty name isn't it?). There we procured two or three trucks of the ANZAC LIGHT RAILWAY loaded them with phones and the other signal gear not forgetting the cooks gear too. Harnessed ourselves to them and pulled and pushed walking in the snow.

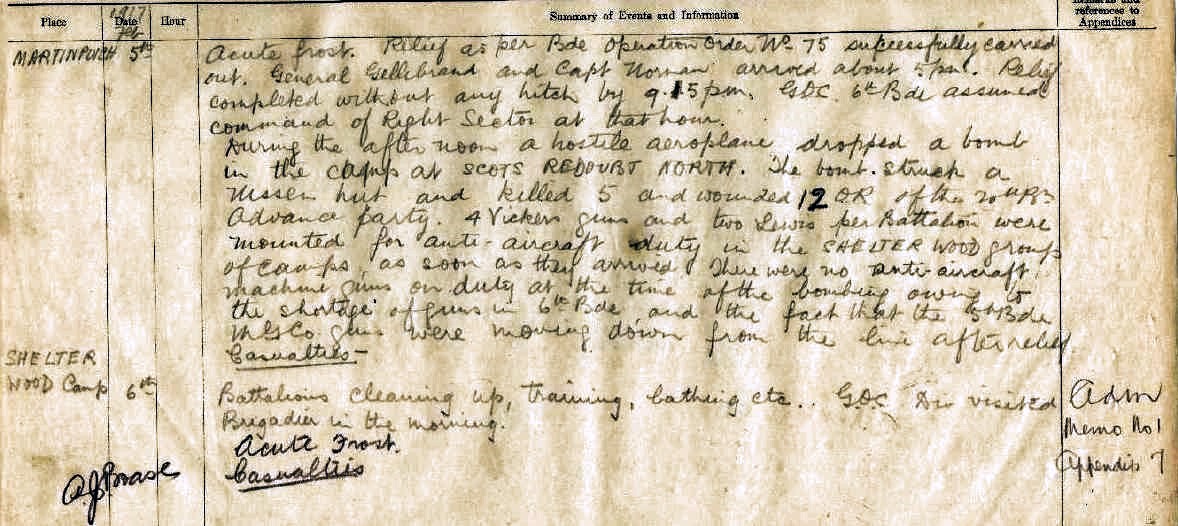

We are at last at MARTINPUICH. Relieved the Scotties. I was sent up to a visual Stn very cold and small dug out I had too. On 2nd I received a parcel from Ella pipe tobacco and socks.

On the 3rd I was relieved from the visual and went back to the switch board. Fritz put a good few of his nasty whiz bangs. Sapper Lee stopped a piece of one and was evacuated.

And so time passed until the 5th arrived and the 6th Bde relieved us. We return to Shelter Wood after a lively few minutes. Coming out the ground still frozen arrive at Shelter Wood 7pm. Fritz plane comes over and drops a bomb on one of the huts and killed 8 and wounded 11. On duty midnight to 8am. Terribly cold.

And so time passed until the 5th arrived and the 6th Bde relieved us. We return to Shelter Wood after a lively few minutes. Coming out the ground still frozen arrive at Shelter Wood 7pm. Fritz plane comes over and drops a bomb on one of the huts and killed 8 and wounded 11. On duty midnight to 8am. Terribly cold.

February 9th we again make tracks to the right of Martinpuich this time. We were a little more comfortable here than on the left. Our dug out was much better too and so we remained until the 27th. During our time here like most other places in line the routine was practically the same. Our planes and his planes busy. Our shells busy, his shells busy. Sometime our boys would hop over and score a win. It was on the 24th of Feby when first we caught the information that he was withdrawing. Everything being in his favor. Foggy weather, visibility very bad.

Click here to explore a map of the Bapaume area. Here you will find many of the towns and villages he refers to : Martinpuich, Montauban, Longueval, Bazentin Guillemont, Le Sars, Flers, Biefvillers, Vaulx-Vrancourt, Lagincourt, Noreuil, Bullecourt and Reincourt.

The battlefield had again become a scene of mud and fog when, on February 24th, all troops were electrified by news that German front trenches at the northern end of the old battlefield had been found abandoned. In a dugout in Loupart Wood, German orders for the retreat to the Hindenburg Line were discovered which suggested the main retirement would take place on 15 March with the German rearguard withdrawing on the 17th; a prisoner there said that the Germans were retiring towards Cambrai - evidently to the Hindenburg Line which ran west of that town. Australians in some parts noted that the enemy flares on their front also rose farther back. Patrols sent into the fog presently found that the Germans were retiring on most of the I Anzac front also, leaving, however, a thin screen of small posts and patrols. This situation had a magic effect on the morale of the Australians. In good spirits, but being careful of booby traps, they followed the withdrawal. By 7.45 am that day, Australian patrols were in the outskirts of the burning town of Bapaume. Moving through the smoking streets they emerged into the almost untouched green country beyond, exhilarated to have the trenches and the mud of the Somme behind them. Patrols pushed back the German screen as far as Warlencourt and to near Le Barque at the foot of the Bapaume heights, where stronger German posts held up the advance. On the night of 26 February, Australians seized the villages of Le Barque and Ligny-Thilloy and they soon had posts below Bapaume.

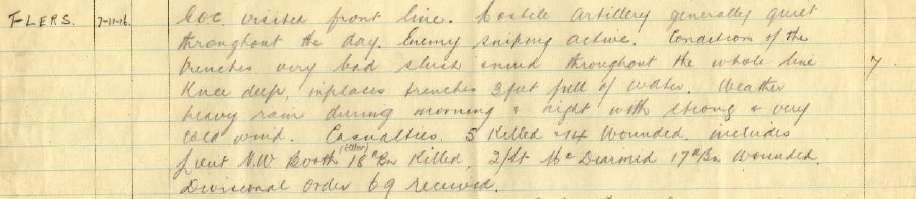

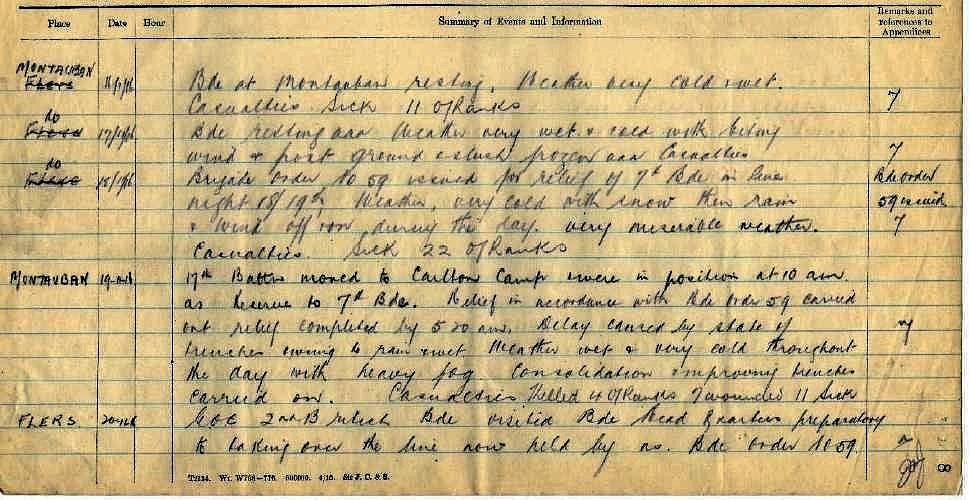

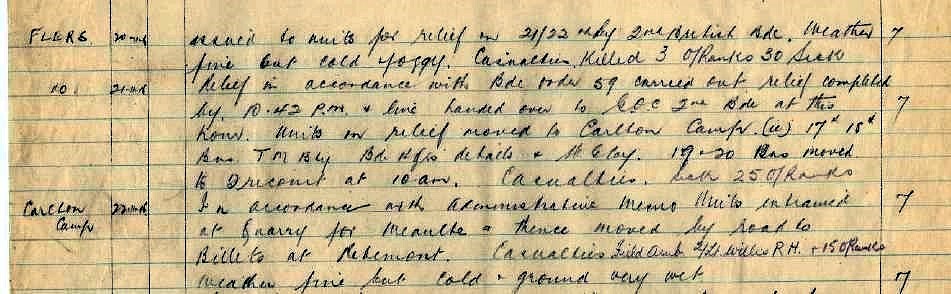

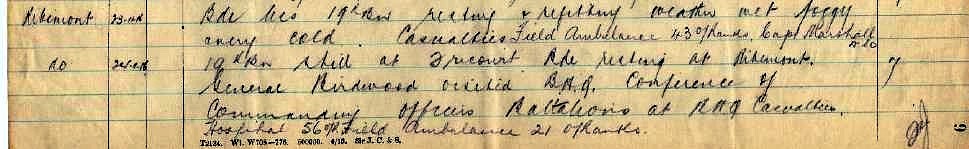

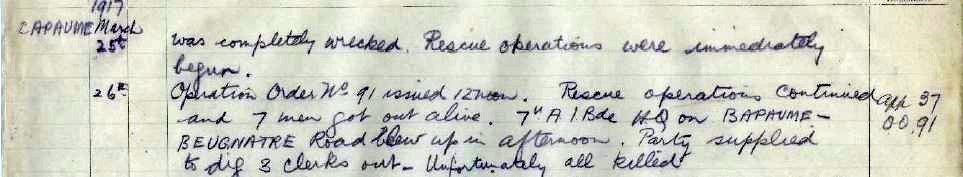

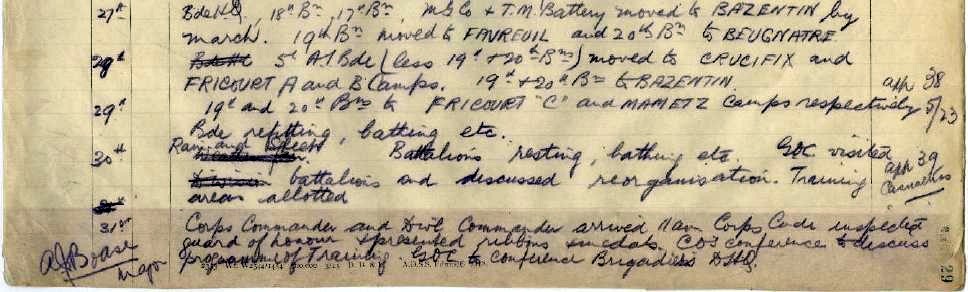

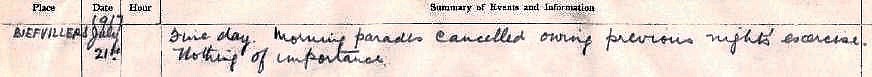

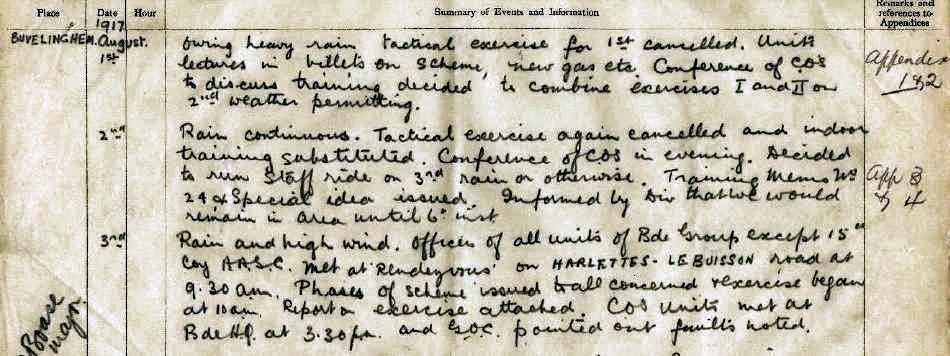

A divisional diary notes for the next few days :

Feb. 17. Slight rain and mist. Poor visibility.

Feb. 18. Foggy and slightly colder.

Feb. 19. Heavy rain during early morning. Dull for remainder of the day. Slight fog.

Feb. 20. Light steady rain since early morning.

Feb. 21. Warmer, but visibility bad.

Feb. 22. Thick fog with light rain.

The Brigade diary diary for the 24th February extends over several pages and details the movement of patrols and occupation of trenches left by the retreating Germans.

It is at this time that we know from records of the 18th Battalion that a major battle took place when Australians occupied Malt Trench, on the heights north-west of Bapaume near Loupart Wood. The Brigade Diary entries for February 27th bear this out. Verner makes no mention of it, however, and as a Signaller he may not have been directly involved in the fighting as were the infantry men.

On returning to Shelter Wood we heard that Kut had fallen and 1700 prisoners. Quite pleased with that news.

The fall of Kut in late April 1916, when British commander Sir Charles Townshend surrendered his garrison of approximately 10,000 men to the besieging Turk force under Khalil Pasha, brought about a reorganisation of both Turk and British forces in the area.

It was on March 6th we again move off to DEATH VALLEY. It certainly wasn't a very comfortable valley at times. Our HQ were OK though best we have had yet in the line some of our make what I mean by our make is British make. We stayed here until the 12th intermittent shelling was going on. Planes were busy. Hardly a day passed without a air duel. A cheer would go up from the boys if a Fritz plane was brought down.

At 3.30pm we left pulling a truck with gear on to go to our new position. After a lot of messing about we arrive at LE-SARS in the morning at 2.30 am very tired and sleepy. During the day the enemy shelled this position very heavily. We relieved the 7th Bde at Le Sars. Fritz was on the move again on the 14th. Our boys kept in touch with him.

On the 18th we moved our H.Q. to a place on Bapaume Road. No sign of Fritz. Our outposts were about 5 miles other side of Bapaume. Heard the enemy was on the move back on a 60 Kilo frontage. Traffic on Bapaume Road was simply marvellous. Heard on the 20th that the 26th Batallion got cut up a bit. Fritz attacked in a armoured train.

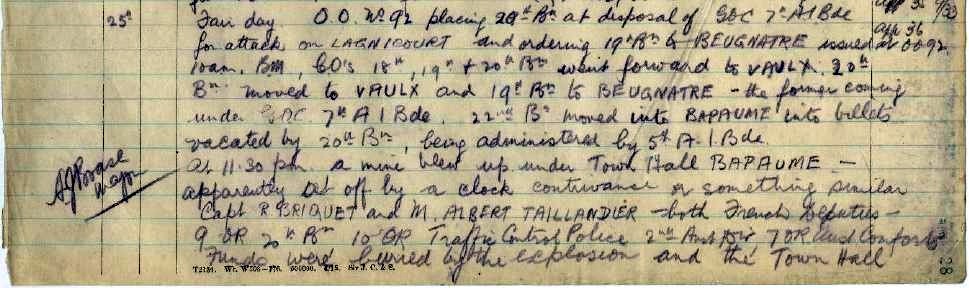

Bapaume was a large German-held town almost within sight of the Australians' trench lines throughout the winter months on the Somme. Suddenly, from 24 February 1917 it became evident that the enemy was retiring. The British advanced after them, and by the morning of 17 March Australian troops reached the outskirts of Bapaume. The soldiers' heightened spirits were exemplified by the band of the 5th Australian Brigade seen here, led by Bandmaster Sergeant Pheagan of the 19th Battalion, playing amid the burning ruins as they marched through the Grande Place into the old town square on the 19th. (Verner was in the 5th Brigade of the 2nd Division).

We left HQ at Bapaume Road on the 20th a place further along the road about one mile. On the 21st we move again for Bapaume this time arriving about 7.30pm. Town still burning. Heard Prince of Prussia Aeroplane brought down and the Prince captured by the 7th Bde.

On 21 March near Lagnicourt, a German aircraft came down in front of the Australians and, as the pilot ran for his own lines, he was shot by an Australian and captured. The pilot, Prince Frederick Charles of Prussia, was carried to the aid-post. Before he died in hospital a few days later, he thanked the Australians and others concerned for their kindness and 'good sportsmanship'. He too, was 'a sport', he said.

Very cold and snowy still. We were lucky in not having established a Sig Stn in the Town Hall as on the 25th about 11.30pm I feel a rumble then a explosion and the town hall was gone. Fritz evidently had a mine under it. Some of our chaps were killed others buried. I was sleeping in a cellar but after that we had to leave these cellars in case they were mined too.

Very cold and snowy still. We were lucky in not having established a Sig Stn in the Town Hall as on the 25th about 11.30pm I feel a rumble then a explosion and the town hall was gone. Fritz evidently had a mine under it. Some of our chaps were killed others buried. I was sleeping in a cellar but after that we had to leave these cellars in case they were mined too.

Booby traps and time bombs had been left behind; one exploded in the town hall a week later burying men and killing twenty-five.

On the 27th we left Baupaume and went back to BAZENTIN. It was a good long march and I wasn't sorry when we reached our destination. Next day we were on the move again arriving at Crucifix Camp at Fricourt. Well there is nothing of importance to relate whilst at this camp.

On the 27th we left Baupaume and went back to BAZENTIN. It was a good long march and I wasn't sorry when we reached our destination. Next day we were on the move again arriving at Crucifix Camp at Fricourt. Well there is nothing of importance to relate whilst at this camp.

On April 8th Easter Sunday I went to early communion and was inoculated in morning went to POZIERS for a walk to view the place of my initiation of gun fire on the 4th of Aug 1916. Things were different then on the night of my arrival our Bde captured the Ridge that was of great importance.

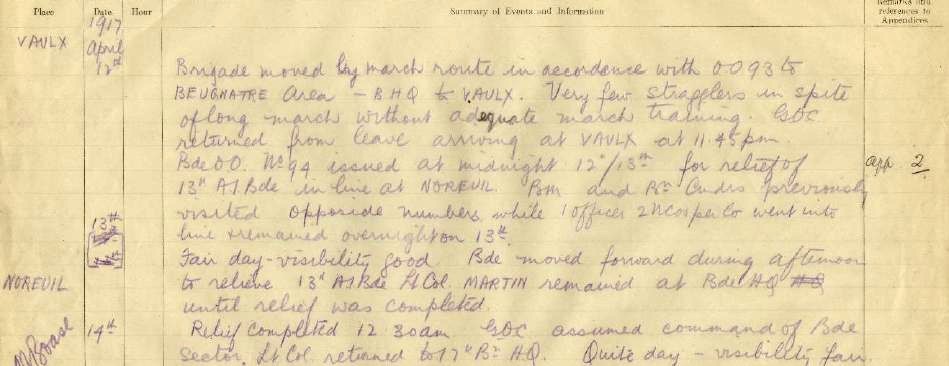

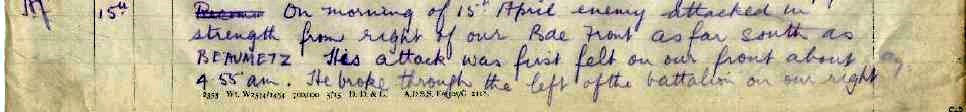

On returning back to Crucifix Camp I went to bed my arm was very sore owing to the inoculation. Next day was very cold. Arm a little better didn't have much sleep. During our time at this place it practically snowed all the time.