Victor Harbor

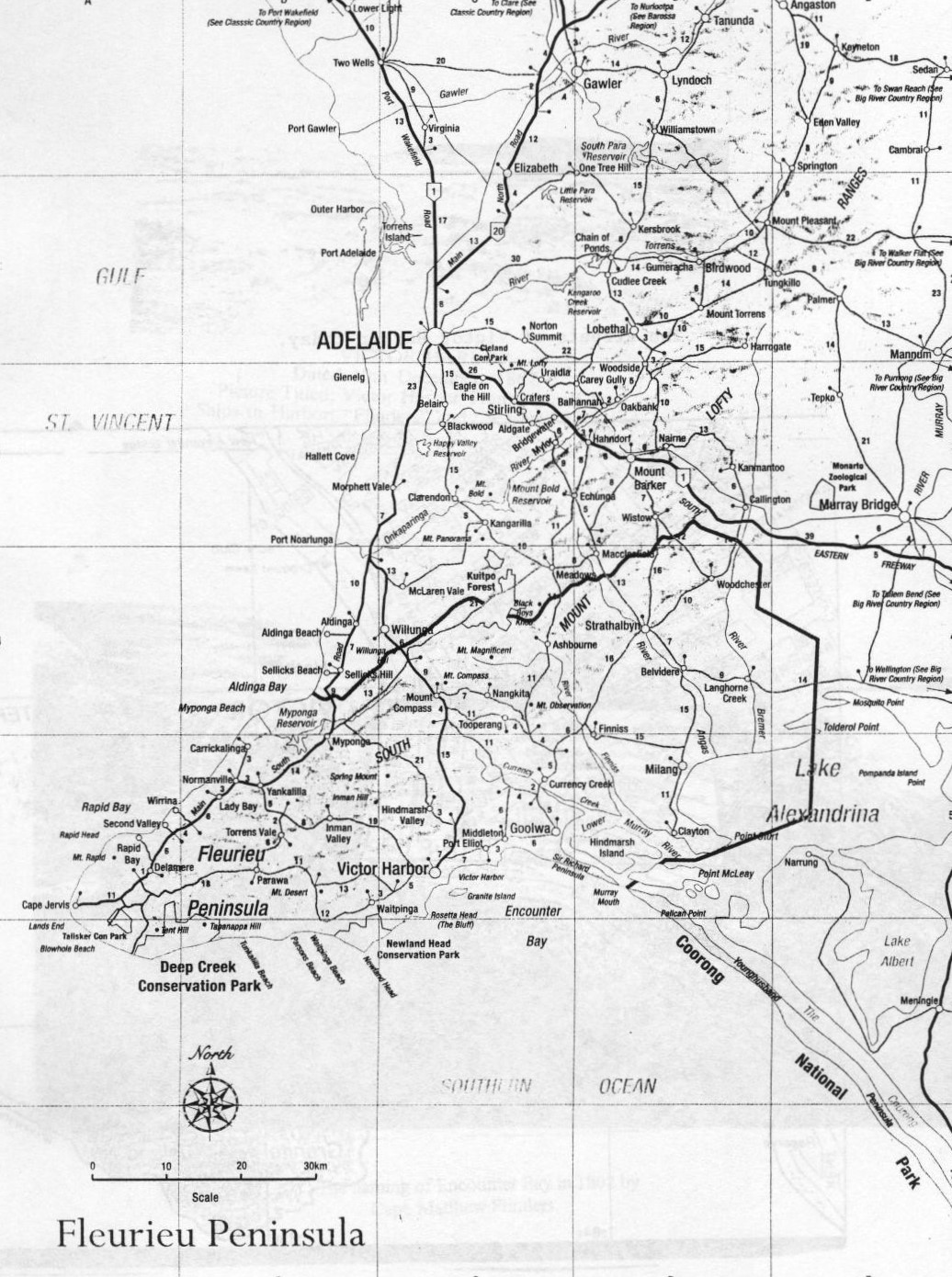

Victor Harbor today is a holiday resort town situated on Encounter Bay some 80 klms

south of Adelaide. It has been prominent in the history of South Australia from the earliest days, having experienced periods of depression and prosperity.

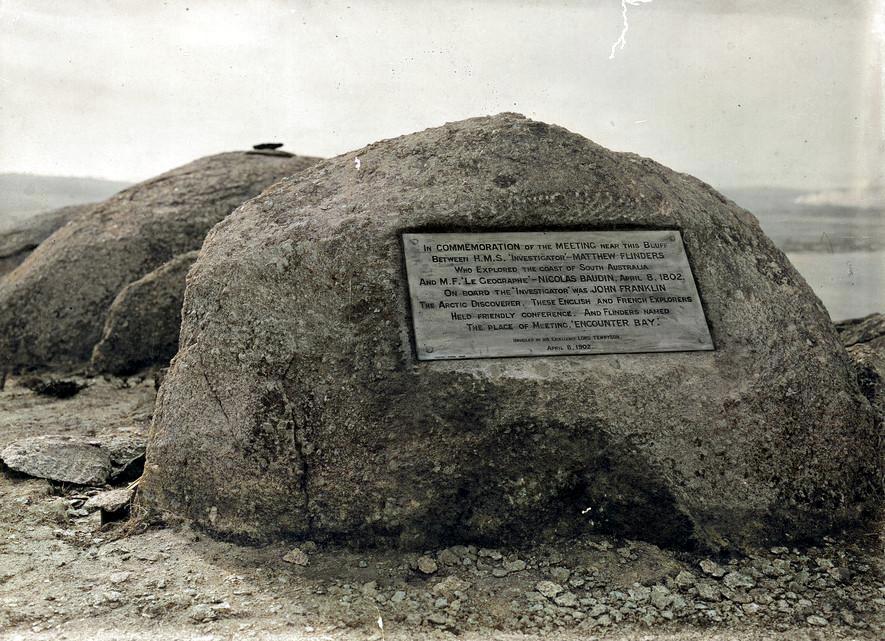

Captain Matthew Flinders named Encounter Bay in 1802. About 17 klms south east at

Goolwa is the Murray River mouth, whilst on the north west side of Fleurieu Peninsula are steep rocky cliffs which contrast greatly with the shore towards Port Elliot where there are long sandy beaches backed by sand hills.

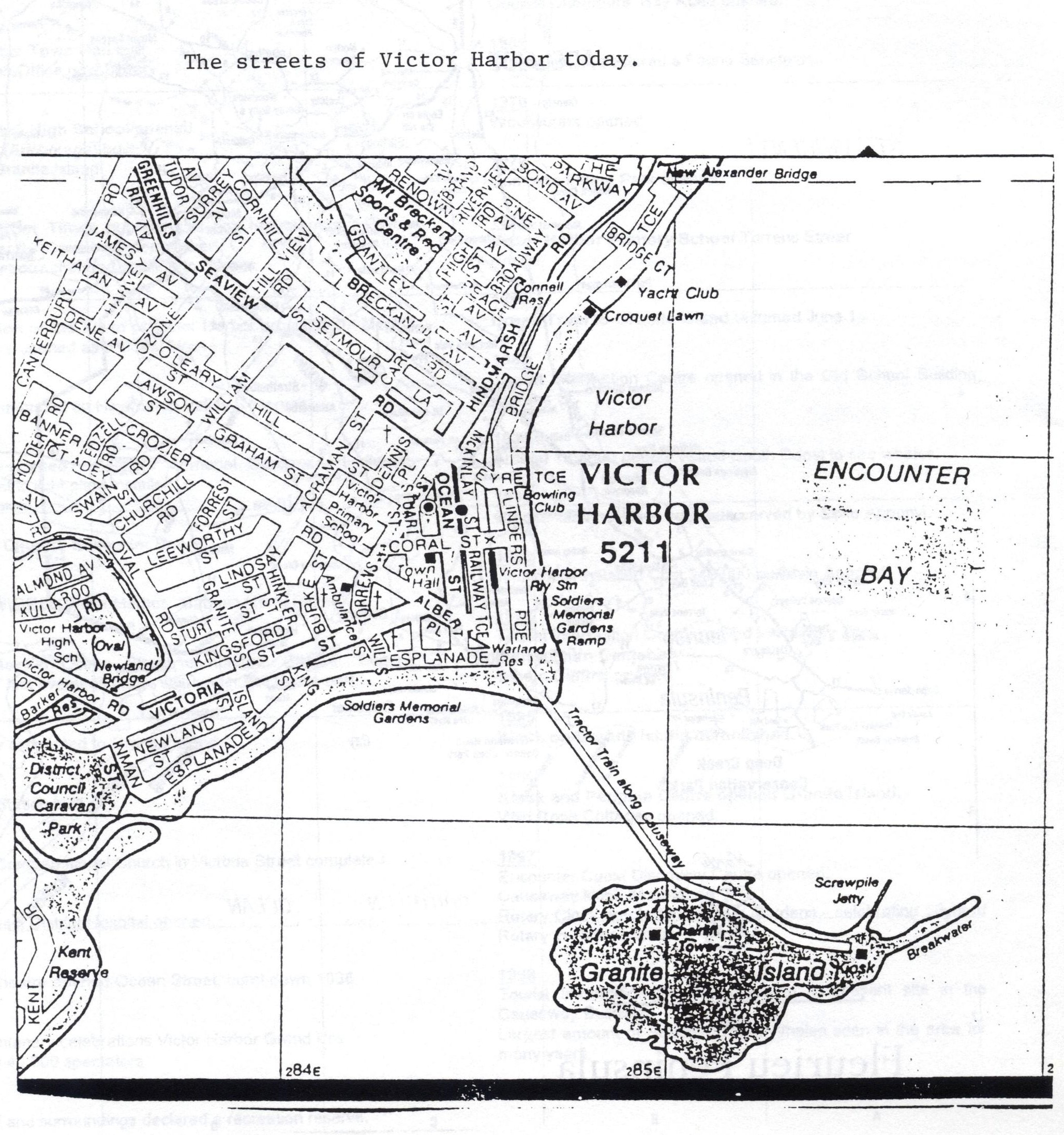

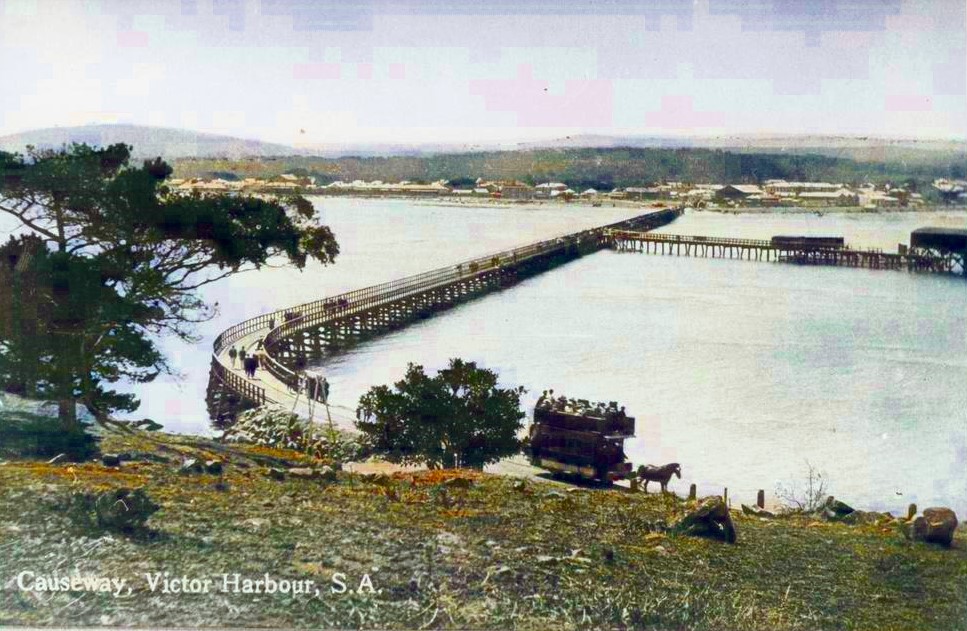

The main features at Victor Harbor are Rosetta Head, known as The Bluff, and Granite

Island lying just offshore, today joined by a causeway.

A Captain Crozier in the ship “H.M.S. Victor” anchored off Granite Island and named the place Victor Harbor after his ship.

At the time of settlement in S.A. whale oil was an important product used extensively in everyday life. A whaling station was set up in 1837. The first commodity exported from S.A. was whale oil from Victor Harbor. At the end of 1837 200 tons had been exported. The business declined and by the 1870's it ceased altogether. Several shipments of whale bones were collected and sent to England for use in the pottery trade. The whaling industry had been a badly managed business that did not enhance the reputation of the district.

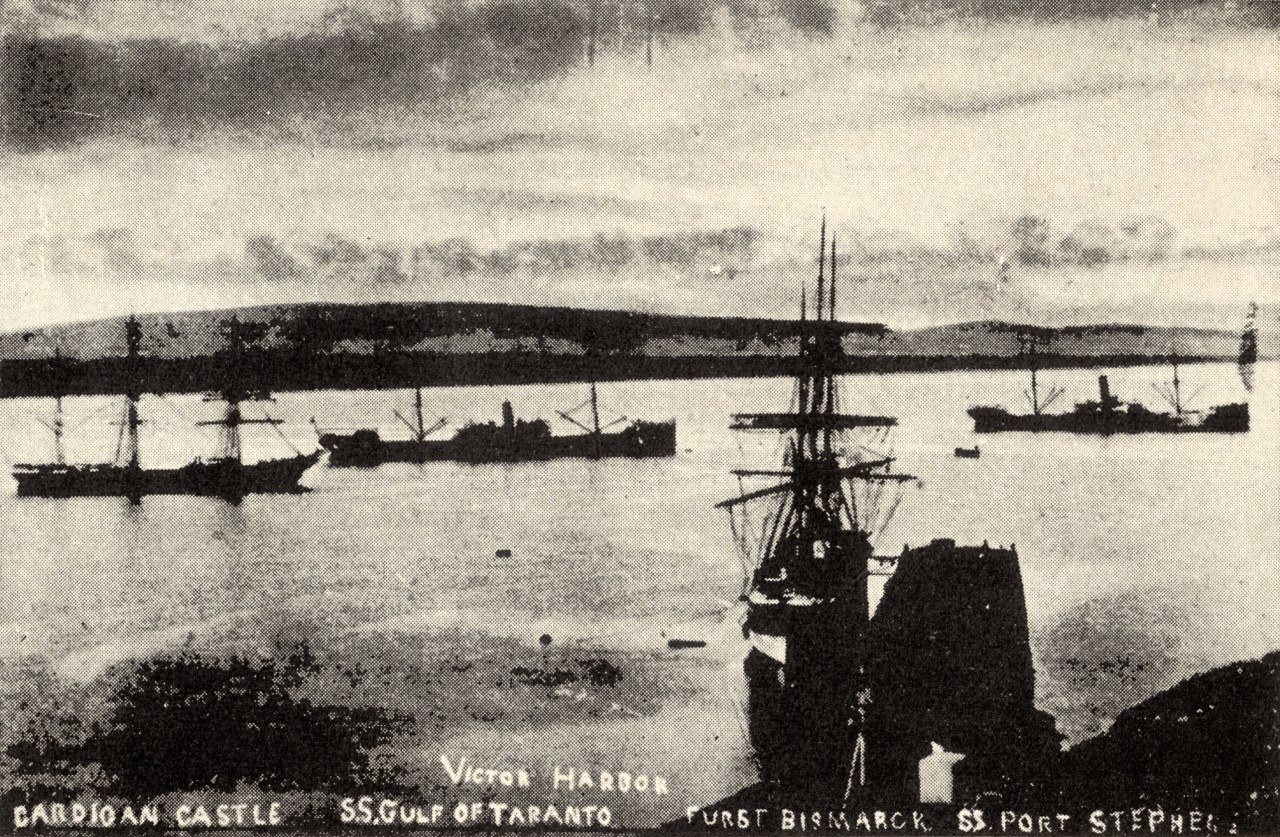

To enable people who had settled inland to move their produce to the coast quickly and cheaply, it was decided to establish a port on the South Coast to handle the trade and produce using the paddle steamers on the Murray River. Because of the unreliability of the river mouth near Goolwa, the heavy seas and rough weather suffered at nearby Port Elliot, conditions were dangerous for sailing vessels. It was decided to construct a jetty at Victor Harbor. A breakwater was built using local granite quarried from the island and the causeway extended.

This became the largest undertaking in S.A. up to that time. Railway type trucks running on rails were pulled by nine horses, which were stabled on the island.

The port was used for local and overseas cargoes as well as receiving such items as the unassembled river paddle steamer in June 1866, brought out as cargo and destined for use on the River Murray. It was assembled at Goolwa.

An unusual happening should be noted of the Norwegian barque Margot.

She arrived in September 1911 to load wheat. During the evening she was due

to sail the Captain went ashore to see the Harbour Master about his departure. He left in a small dinghy to rejoin his ship and was never seen again. The dinghy and one oar were located but the Captain's body was never found. An Inquiry was held but no explanation of his disappearance was found. This delayed the sailing. The ship's carpenter was appointed Third Mate and the “Margot” finally departed on 10 November 1911.

She did not get far and went ashore on the Coorong. This was subsequently stated as due to inexperience of the Third Officer, who was on watch at the time of the mishap. Sailing too close to the shore causing the ship to run aground. All the crew reached shore safely.

When the news of the tragedy reached Victor Harbor, the lifeboat “Lady Daly” stationed there was prepared. The usual crew was not available at the time so local men volunteered to man the lifeboat. By the time “Lady Daly” reached the wreck, the cargo of wheat had “sprung” the timber and was giving off dangerous fumes. The barque was beginning to break up. After completing their job at the wreck the lifeboat and crew set out to return home. Due to an offshore wind they were blown far out to sea and to the great worry of the townsfolk did not reach home for three days. But consternation soon turned to joy when the lifeboat and its crew returned safe and sound. (This information was obtained from a visit to the Historical Society at Victor Harbor. Whilst there I came across a photograph of the crew on board the lifeboat. Amongst them were Arthur Jarvis and his son Keith Jarvis.)

With the development of the harbour it soon became obvious that a lighthouse was needed. It was erected on a high tripod and operated by a kerosene light that could be seen for 8 klms. Eventually a gasoline-burning lamp replaced this in 1884. In 1955 an electric fixed light was established to act as a guide for fishing boats using the harbour.

Today, of course, the island is a showpiece for tourists - its role has varied from whaling station to overseas port - to tourist attraction. It has been beautified with walking pathways, seats, play areas, a ramp to the top of the cliff and many trees have been planted.

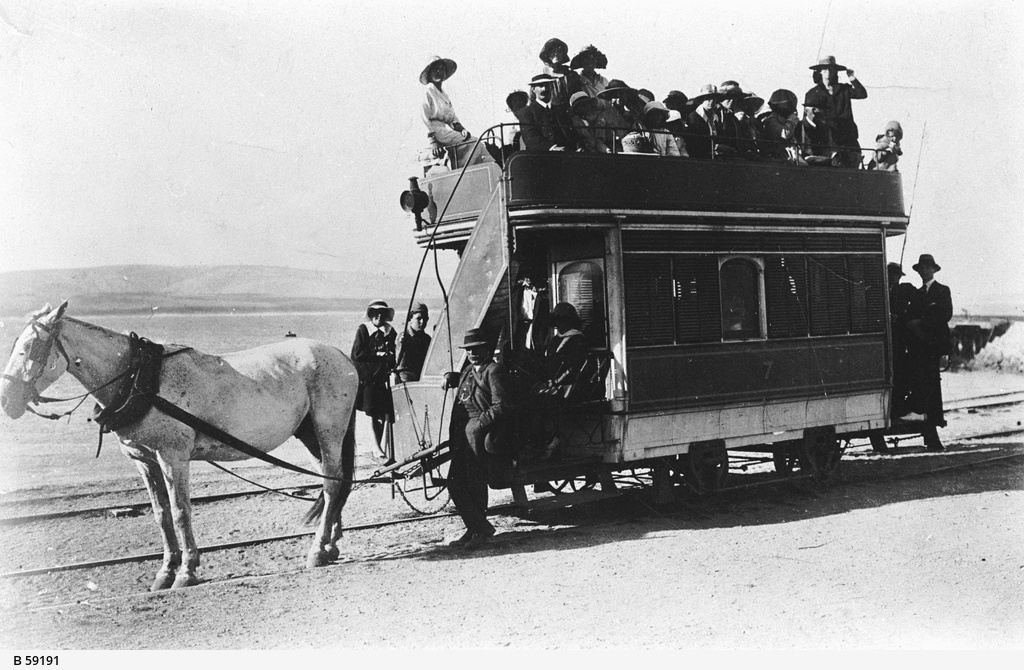

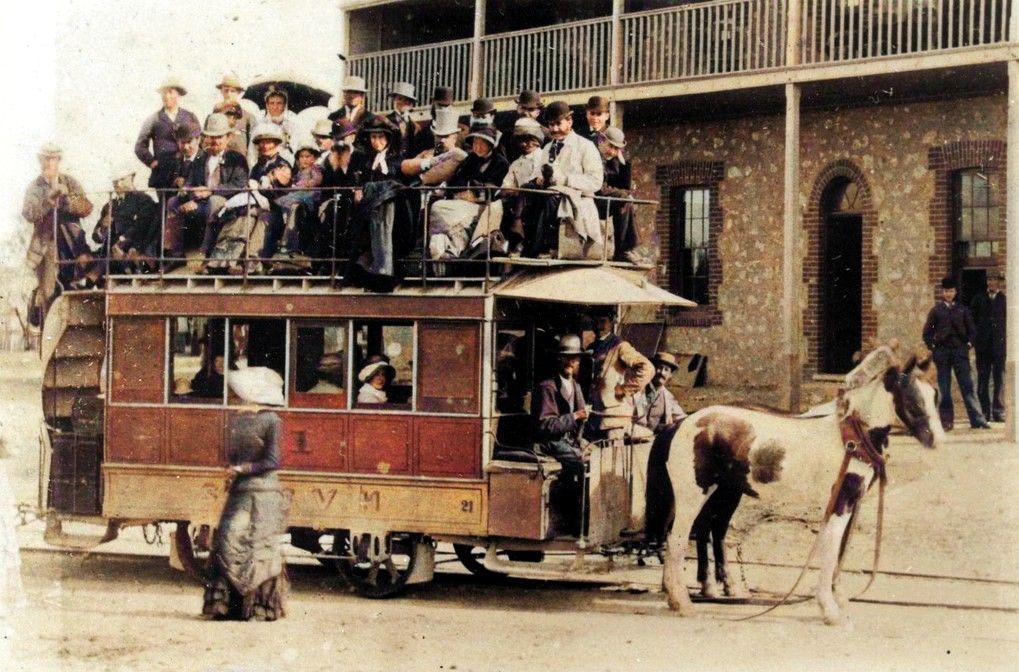

Originally, when used as a seaport, horse drawn trucks transported goods, later small

locomotives were used, and in 1894 a passenger service commenced using horse drawn trams. The cost was 3 pence return. At one stage a double decker tram carried up to 36 people, and a Ferguson tractor camouflaged as a train operated, pulling four locally built carriages. Today they have returned to horse drawn vehicles as a tourist attraction.

Victor Harbor as a town did not exist until 1863. The only substantial building was the

Police Station erected near Police Point. Several small huts had been erected on the town site. In 1863 two bridges, one over the Hindrnarsh River and the other across the Inman River, were opened. Their opening marked the beginning of organized settlement within the boundaries of the town. Before these bridges were built people had to ford the rivers, consequently the town was not visited by many people.

The first stone house was built on the site of the present Hotel Victor, and became the site for the present modern hotel. A large railway goods shed was built in 1864 to cater for traffic on the original horse drawn railway. The telegraph station was also completed in 1864, making communications with Adelaide much easier. The Bank of S.A. opened its first branch in 1865.

The newspapers of the day reported that by the middle of 1864 a large number of buildings were being erected and the town was assuming important proportions. Kerosene lights originally lighted the streets. These were replaced by electric lights and electricity was connected to homes in the town. Better roads and footpaths improved the appearance of the town and added to the welfare of the people.

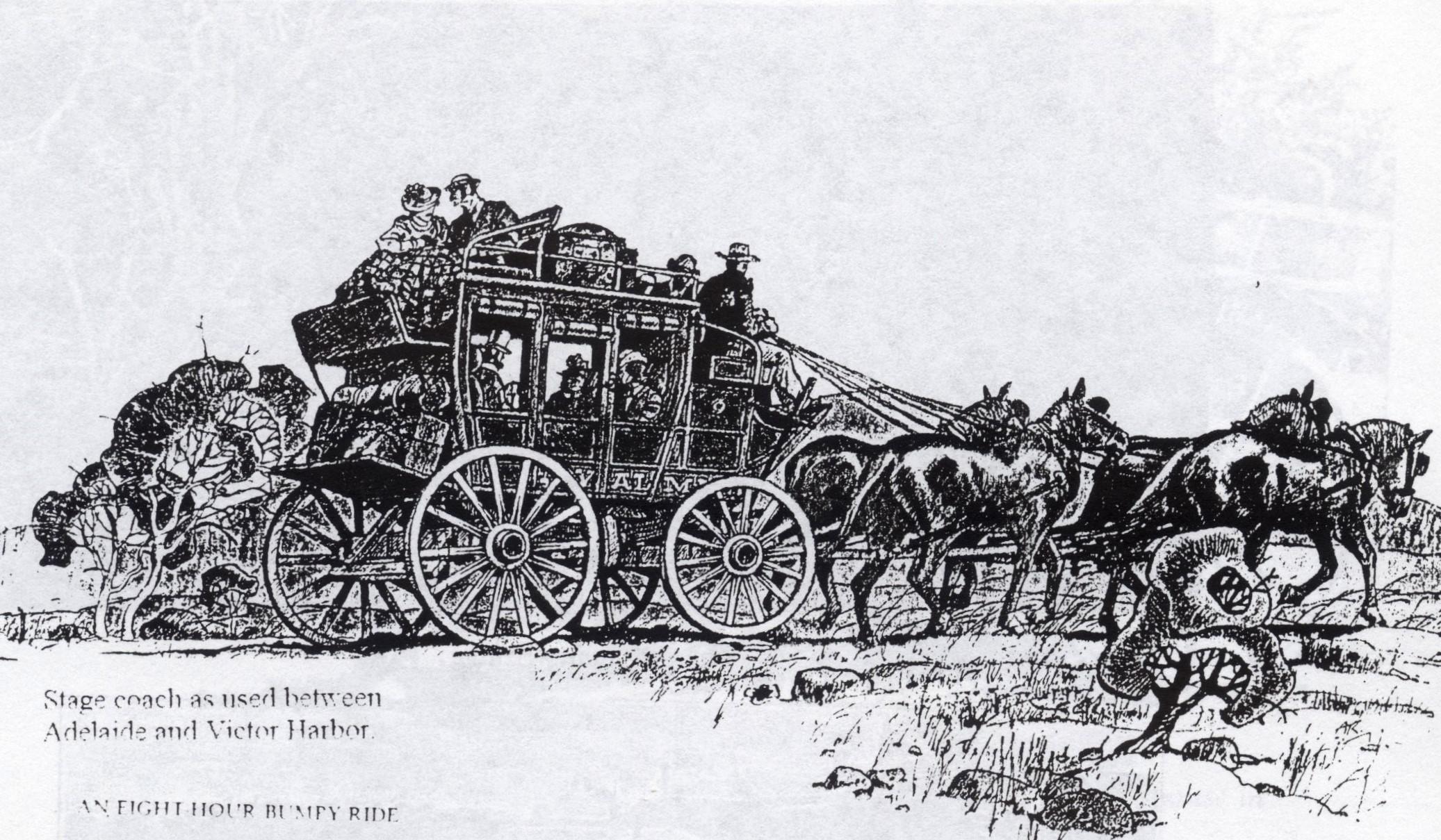

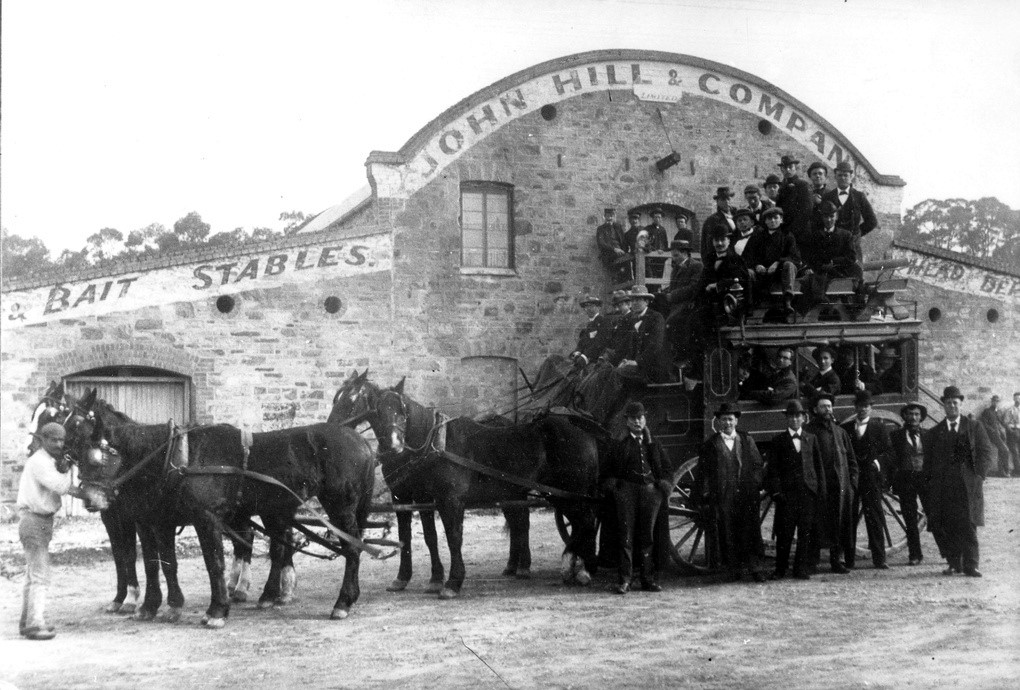

Travelling in the early days was a major undertaking. The first overland link between Victor Harbor and Adelaide was by bullock wagon and the journey of about 82 klms usually took three days. Cobb & Co. replaced this mode of travel with coaches. The service operated between Port Elliot and Adelaide taking 8 hours, the price for a single fate was 14 shillings and 6 pence. The return journey took 19 hours. Cast your mind back to those travellers and imagine how they would have felt on arriving at Victor Harbor after being jolted around in coaches with hard seats, travelling over roughly formed limestone roads. One can only imagine the discomfort they experienced and understand why people in those early days only travelled when it became absolutely necessary.

The road to Victor Harbor was bitumenised in 1928. The same road has been rebuilt, removing curves making it a comfortable scenic drive of 2 hours or less, compared to the then 8 hour trip in a Cobb & Co. coach.

This concludes the many facets of Victor Harbor, from the first shipment of whale oil, to the great days when large ships called and loaded cargoes of wheat and wool, to how the activity ceased quiet quickly due to government's centralization policies.

The area grew from a few rough huts into a thriving community with large buildings

worthy of any town. The character of the town has changed from a commercial aspect into a place with great tourist potential. This is the main draw card today and it is hoped it will maintain its place as premier tourist resort in South Australia.

The physical sets of Inman Valley. The Valley situated on Fleurieu Peninsula approximately 80 klms south of Adelaide, runs in an easterly direction from Bald Hills to Victor Harbor. The River Inman flows towards its mouth at Encounter Bay and contains water all year round.

The following passage from the Geology Department, University of Adelaide, briefly outlines the local geological history.

Approximately 270 million years ago (Permian Age) ice covered much of southern

Australia and glaciers or ice sheets moved down from the highlands smoothing off any

exposed rocks over which they passed. Such smoothed bedrock surfaces called

“pavements” are found in a number of places in the Victor Harbor area. As the climate

moderated they melted leaving a considerable volume of sediments deposited in lakes and bays behind the retreating ice. These sediments, known as “till”, consist of clay and sand and contain occasional large boulders, or “erratics”. The erractics here are composed of granite, or other basement rock types derived from this locality or from further southeast.

They are presumed to have been dropped from icebergs floating in the Permian waters. A spectacular example can be seen at Selwyn Rock, located at Glacier Rock Teahouse in Inman Valley.

Here a large rounded erractic of granite embedded in till occurs in the creek bank adjacent to a well-expected glacial pavement. The preservation of the Permian sediments is rather remarkable considering the soft and poorly consolidated nature of the till and the fact that most of the area has been exposed to erosion of the land mass over the last several hundred million years.

What is known locally as the “Coal Bore”, located in the top end of Back Valley, was

drilled to a depth of 300 meters, thought to be the floor of the glacial valley.

Discovery and early description. Europeans first sighted the Valley in 1831 when

Captain Collet Barker crossed the Peninsula from St. Vincent Gulf and travelled through the valley area to the Murray Mouth, where he met his death, his support party returning via the Inman Valley. The Valley was named after the first Superintendent of Police,

Henry Inman who was appointed by Governor Hindmarsh on April 1, 1838, His salary

was set at two hundred pounds per annum. He resigned in 1840. Henry was a son of

Professor Inman, of Portsmouth Naval College, having served as a lancer in the British

Army and described as having been tall and powerful - “bold as a lion”.

The first Census of South Australia was taken by Mr. Inman on 30 January 1839. He returned to England and was ordained as a minister of the Church of England.

Two aboriginal names for the Inman River are Moo-oola and Moogoora.

Mr Frome, the Surveyor General succeeding Colonel Light travelled through the Valley of the Inman in 1839 and did some drawings that are now in the S.A. Art Gallery. Governor Gawler visited the district in 1839 and his description of the valley is recorded in the S.A. Gazette as follows:

“Twenty five miles to the south of the Inman in Encounter Bay runs a lovely Valley,

varying from six to two miles in width, well watered and rich in soil for agriculture and

heritage for pasture. In this Valley division hills, which separate the eastward and the westward waters, are about ten miles from Yankalilla. Their summits are covered with pasture, and their height is not above 100 metres above the sea, while that of the precipitous mountains which bound the Valley to the north and south is from 400 to 620 metres.”

The blue haze on the Inman Hills fascinated travellers in the early years when viewed from Bald Hills and were often likened to the Blue Mountains.

Early settlements. Early settlement is bound up in the history of Bald Hills. The upper

portion of the Valley extends beyond Sheoak Hill and includes the heavier type soils on the hills dividing the Inman and Back Valleys all within the Bald Hills area. It is difficult to say when the first settlers arrived, about 1842. A Mr. Field leased a large area of land before land grants were made and overlanded cattle from the eastern states in 1837,

The early 1840's to 1850 seemed to be the period of considerable settlement. By 1850 Bald Hills was well settled, and to a lesser degree the fertile areas of the Inman Valley. The better type soils were selected for wheat growing and throughout the area furrows can still be seen where the farmers ploughed their fields - usually a portion of their 80 acre section.

Those early settlers had by necessity, to be self-sufficient and many of them brought with them trees and cuttings to establish their gardens. To have a horse, a fruit and vegetable garden, and a few acres enclosed with a post and rail fence was considered important progress. They found the reliable rainfall most successful for the growing of wheat, with flour in the early boom years selling at twelve pounds per bag. Yields of 30-40 bushels per acre were common from the fertile virgin soils.

Harvesting by hand sickle was common in the first few years. Threshing was accomplished by means of a large, ribbed and tapered log, some 6 metres long, anchored at the small end and motivated by two bullocks attached to the larger and outer end to roll over a circular area. The heads of wheat placed within this area would be crushed in preparation for hand winnowing in the wind. In this way large quantities of wheat could be threshed with a fraction of the effort needed for hand flailing. The farmers would then travel to the flour mills at Encounter Bay, with their wagons loaded with grain and pulled by teams of bullocks or later horses. The fields were ploughed with single furrow ploughs drawn by bullocks. Until horses became plentiful bullocks were the main draught animals for quite a number of years.

From the early records we can assume that a good number of settlers came to the Inman during the l840's. However, the surveys had not then been made and it is presumed that these settlers leased, rented or “squatted” on the land. 1850 completed the survey for the Inman Valley-Bald Hills area and by 1860 most land was taken up. A late survey of the poorer country or “wastelands” was opened up for selection in 1884. Obviously there were many other people in the area who rented or purchased land in later years.

Life was not easy for these early settlers who had only a limited supply of tools and

equipment which they bought with them. They often had to make do with what was

available locally. Fortunately, with the early settlers came several excellent stonemasons, who set to work immediately to build permanent and solid homes with the stone that was quarried in the nearby hills. Floors were often slabs of slate. Those who could not afford to employ builders had to set to and build a home with little more than their own hands and with whatever materials were readily to hand - clay and light timber. Many homes were built of this clay or “pug”. “Pug” or “wattle and daub” consisted of straight wattle sticks lashed or nailed together with mud or pug plastered in and around to fill up the cracks. The roof would be of thatch and the whole house would consist of only 2 or perhaps 4 rooms of low profile and often partly dug into the side of a hill. Large slabs of red gum or slate formed the rather uneven floor.

Aborigines. The natives of the area were the Encounter Bay tribe, and it appears that they gave little trouble and were generally ignored by the white settlers. They valued Back Valley as a hunting ground referring to it as “Pondyong” which means plenty - plenty of water and plenty of kangaroos. At daybreak the kookaburras would burst into laughter, countless bush land birds twittered and chattered, and the movement of water could be heard as it made its way down the valley.

An interesting story is told of a William Isaac Lush, who as an infant in the mid 1840's, was put out in the sun in a crib. A group of natives, accustomed to receiving gifts of tea, sugar and tobacco, called at the hut. A lubra with a piccaninny, on seeing the white baby, decided she liked it best. The swap was quickly made, and the lubra made off to the scrub with William Lush, leaving her own black baby in the crib.

Fortunately Mrs. Lush, who with the valuable aid of the sheep dogs, headed off the lubra soon discovered the change, and the infants were returned to their rightful mothers. Another version of the story says that the Lushes had to go to the native camp on the beach to retrieve their child. (Taken from the book titled "The story of Victor Harbor" by A.A. Strempel).

An account given by William Joseph Barratt, oldest son of an early pioneering family, gives us an insight into life in the l800's when he wrote the following at the age of 90 years:

“My parents, William James and Anne (Gibson) married in 1846 and soon afterwards lived at “Glenbrook” on Lower Inman Valley. James, Anne and I were born there, and I was 4 years old when we went to live on section 306 at Back Valley, which opened on to Bald Hills. At that time, nothing had been done to the scrub. We were reared there and Mary, Prudence, Sarah and Frederick were born there. When I was 6 years old and James was 4, we had to drive a team of bullocks for father when he was ploughing. At harvest time we had to cut wheat with a sickle for reaping. We cut it up and put it in heaps and father tied it. Father afterwards bought sections 395 and 396 near Lower Inman. He couldn't grow wheat on it, so it was used for dairying and later sold. James and I rented it for three years, then I took it over for another seven years. By this time I was 30. In 1895 I finally settled at Torrens Vale.” (Taken from the book titled "The Echoing Valley". A tribute to the pioneers of Back Valley near Victor Harbor. Compiled by Eric Richardson (NLA reference)).

It is quite possible that the area near the Murray River mouth and the coast westward to Port Elliot was known to the sealers who lived on Kangaroo Island as early as 1828. However, the first recorded instance of white men on this part of the South Australian

coast was in February 1830 when Captain Sturt and his party reached the sea after their trip down the Murrumbidgee and Murray rivers in a whale boat. It must be noted that they only saw this coastline from the sea, not being aware of the large river mouth's existence. Sturt reported a “disappointing outlet to the sea”.

Goolwa was chosen as the river port terminal, handling the wheat, barley and wool trade from the paddle steamers on the Murray. After a great deal of deliberation a railway line was built between Goolwa and Port Elliot which was considered to be the best place for a seaport. This consisted of 6 miles of track being laid and was officially opened in May 1854. The average speed of all trips was about 7 m.p.h.

Once the line was functioning, more people moved into the locality and the scrub around the area was cleared. The land yielded good crops, the growing river trade created more work and this in turn attracted more people to Port Elliot.

Settlers arrived, having moved south from Adelaide, selected land along the foothills, buildings were erected in scattered locations, and a road from Goolwa to Victor Harbor formed.

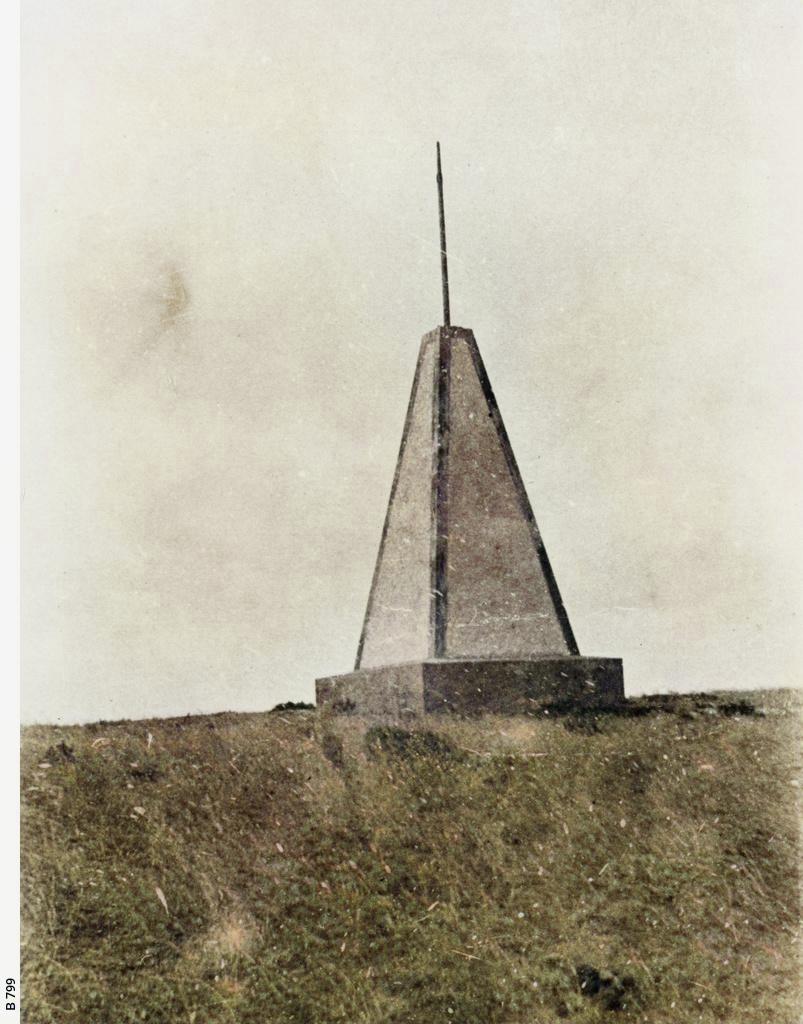

The stone walls of the Congregational Church comprised the first substantial building in the town, on Montpelier Terrace, remaining unfinished until 1853 when a thatch roof was added and the church completed. In 1852 the Port Elliot Hotel was built on the main road, with a large assembly hall used by the townspeople. Extensive stables as well as yards for bullock wagons were provided. Also in 1852 the obelisk on Freeman Nob was erected as a guide for shipping, a point which helped the Sealers on Kangaroo Island. Nearby the Harbormaster's Cottage was built and used for the first postal services in the town.

Fresh water was a problem, especially as ships coming into the port needed to replenish their supplies. At a point about one mile inland there were several natural springs providing good quality water. A site was selected to build a tank as a source of supply, pipes eventually laid and water was used for shipping and also for townspeople, using a hand pump. This method was used until the l870's when the pipes corroded. Eventually the town was connected to the main supply for the whole of the South Coast.

A Police Station was erected, stables for the police horses, a store, a flour mill, guest house and the Southern Argus newspaper was first produced in March 1866. In 1868 the newspaper was sold and the printing works transferred to Strathalbyn. A new post office was built a Court House and the first public school in the town was opened in 1857.

Up to this time the development of the town had been dramatic but then the pace slowed because the port had not proved suitable and the shipping disaster of 1865 sealed its fate.

This and other tragedies brought about the transfer of the port facilities to Victor Harbor. Serious bush fires devastated large areas in the summer of 1859 resulting in a further setback.

In 1861 it was proposed to extend the railway line to Victor Harbor and eventually a new railway station was built. A coach was now running from Adelaide by Cobb & Co., the journey costing 14 shillings and 6 pence one way and took 8 hours to complete.

Port Elliot grew and with the transfer of shipping to Victor Harbor adopted the role of

tourist town. The town has experienced affluent times as well as disappointments and

people not only supported their immediate area but the whole of the South Coast.

The town began in 1852 and developed at a rapid rate until 1864 when the port was moved. Development then slowed and the tourist development has continued successfully to this day.

The South Coast and Fleurieu Peninsula has played an important part in the history of

South Australia with vital contribution being made in helping to develop the inland towns along the River Murray.

Memoirs of Walter Buxton Bruce, retold by Anthony Laube. Gillingham Press, Adelaide. ISBN 0 646 12648 2. Walter Bruce 1898 - 1989. (NLA reference).

Walter Bruce was born in the back bedroom of his Granny's house in Burke Street, Victor Harbor. His mother was Annie (Buxton) and his father William James Bruce.

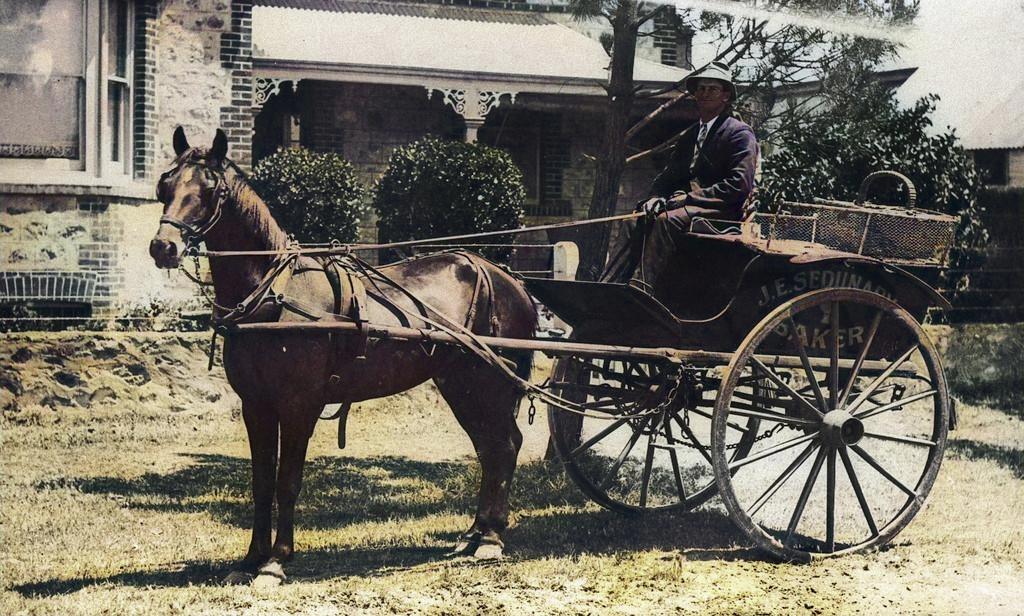

When he finished school my Granny arranged for him to learn butchering from Mr.

Field. Eventually, he drove the butchers' cart for Birds' up to the Bay and all over Victor Harbor, selling meat. The cart had two wheels was all painted with a chrome rail around the top. The inside was duluxed white and had vents, and hooks to hang the meat on. He would cut what was wanted as he went. Walter often accompanied his father on the cart. He earned about 30/- a week.

Walter Bruce's life spanned almost a century which has seen violent changes in society and the horrors of war on a scale unimaginable at the close of the l800's. He and the people of Victor Harbor retained a sense of community that was forthright and realistic, ever tolerant of the “trimmers” in there midst.

SCHOOL

About 1905 a Nellie Jackman taught us in the junior class, on the comer of the old stone building. There was just one building in those days. There was another room at the back, of the little room where children were taught.

Stan Hyde, Darcy Honeyman and the JARVIS BOYS were all in the junior class with me and the Bradley girls. A teacher Miss Isobel Christian White was from Goolwa. She was very clever, she was a Bachelor of Arts, having studied arts and crafts at the University and music at the Conservatorium in Adelaide. She was tall with auburn hair and she always wore pleated serge skirts - cream for summer and navy for the winter. She was very kind and always went to a lot of trouble for concerts and musicals, even buying materials for costumes out of her own pocket for the poorer ones. After school she was always willing to help with our homework and when any of the children were sick she would visit and take them fruit. She could paint and draw. She played the piano for singing (we all bought a shilling to pay for the cost of the piano.) It cost about 20 pounds. We loved to sing.

“The word “trimmer” - its derivation as a colloquial term is uncertain, though in Victorian England, a certain Mrs. Trimmer was a writer of sternly, moralistic, children's stories. Later, in Colonial Australia, the term was applied to the police troopers. However, our grandparents used the term to refer to anyone who was a “character” or, at worse, anyone of bad character. The favour of the times or the idiosyncrasies of the characters involved.

The big room at the front of the school was in tiers, so that you could see the blackboard above the head of the person in front. It was just painted on the wall.

Another time when we returned from holidays there was a green painted blackboard nailed to the wall. We had four terms in those days.

There was a room on the end of the school where the girls were taught domestic arts, they had a stove to do the cooking on. The girls also learnt sewing and they were taught on a sewing machine a “Busy Bee”.

We marched into school to the tune of “Men of Harlech” played by a teacher. We always sang the National Anthem “God Save the Queen”. Singing was taught on Friday

afternoons.

We played knucklebones, cricket, football, marbles, skipping.

On Arbor Day we planted trees at Grosvenor Gardens. Circuses were held there. Children were asked to write a composition after their holidays and the following was written by Walter Bruce:

Victor Harbor, 8th Oct. 1912

Dear teacher,

We had our school holidays last week. We broke up for the holidays on visiting day. on the Saturday there was a football match. The Mallala and Victor Harbor footballers. The Mallala foot ballers drove to Victor Harbor in eight large motor cars. It was a very exciting game. some of the children spent their holidays in town. During the holidays I

went to the beach and gathered shells. I watched some ladies playing tennis. In the afternoon I went out in the scrub, and got a nice bunch of wild flowers. I went over to the breakwater and watched the large breakers. During the holidays we had a few wet days. I went for a walk up to the Hindmarsh Bridge, and watched some men fishing. I spent my holidays very enjoyable.

I am,

Your obedient pupil

Walter.

The inspector used to come and gave tests, then gave the children a half holiday

afterwards. The boys used to say, “Come again next Friday, Mr Goode, and give us

another half-holiday”.

On Empire Day, Mrs Cudmore from “Adair” always gave us six footballs for the boys and a dozen skipping ropes for the girls. She was a very nice person.

Cadets were on alternate Fridays. We were called up once a fortnight from two until four. It was compulsory to attend. Our guns were kept in the old Wesleyan Church. We had to drill there - where Lindsay Street is now. The rifle butts were kept out at Mr. Welch's place at Hindmarsh Valley. When it was wet we had to clean the rifles and if anyone purposefully missed practice they were sent to Largs Bay to clean the rifles for a week.

You joined the year you turned fourteen, that was compulsory, and went until you turned eighteen. A colonel Malpas was in charge of the boys at first. He was well-liked and quite lenient with them. He was from Willunga. The hats they wore were turned up at the sides with a number in front. They wore puttees. (Material used to secure trouser legs to boots. Protection from sticks and snakes etc.). They were a nuisance - you had to wind them round and round your legs.

BURKE STREET

I remember a time when it was all paddocks from St. Augustine's hall up to the corner. All the blocks between there and Crozier Street were empty the land belonging to the Lindsays.

The house belonging to Granny Bruce was built in 1911 Lawsons had the block next door and they had a small iron house. It was just two rooms, a kitchen and bedroom. The Jarvis' lived there at one time. Mr. Arthur Jarvis and his family. Little Mrs. Jarvis had a hard time of it. They had a big table in the kitchen which they would push right up in the comer by the window, and the two older boys slept on that. Les Jarvis, the youngest, was born in the bedroom, I think. Harold Jarvis married Belle I remember swimming in the mouth of the Hindmarsh River. There was a swing bridge .

There would be Darc Honeyman, Harold and Keith Jarvis and the Hyde boys. We'd wait until some of the girls were halfway across and we'd make it swing. The girls would scream! Later in 1910 it was carried away in a flood. They played football in Hays paddock where Gantley Avenue now is. The boys would climb the olive trees and belt Belle Inglis with olives - she was always barracking the players. Photo of team on page 82 Keith Jarvis. (Photo of swing bridge page 48).

NEW YEARS DAY

Was always a big thing at Victor. There'd be two tram cars to the Island, both full. It was murder to walk on the jetty. The organizers would get up at five o'clock to decorate the causeway, tacking flags all along it. There'd be people all over the rocks and a seat was hard to find. They had a flagpole right on top of the Island with flags on it. Games used to be held on the Working Jetty. That's long gone. There was the old greasy pole with a feather stuck on the end of it. Very few men were able to get to the end and get the feather. There were prizes for that.

The Yacht races on New Year's Day used to look lovely, all out there on the sea. The

Rumblelows, the Williams, Jarvis's and Jeffreys, they all had yachts.

Lasso, I think his name was, had a stall selling cool drinks and fr11it. This was just a piece of canvas on poles. There would also be a beer stall.

THE ISLAND

There used to be a little chuffing steam engine to take wheat across to the ships. The

cockle-train went right across to the Screwpile Jetty with wool. On the end of the breakwater there was a light. It was a tripod structure with an iron ladder. But the sea air and the water washing over it all the time corroded it. Mr. Jeffreys used to climb the iron ladder to light the lamp. All the old pieces of machinery that were used to build the breakwater were left lying around Granite Island - where they had been left.

Before the war, (World War 1) the military used to camp on Granite Island, above the

cliffs. They had a cannon and they would post warnings to the fishermen before they fired at Seal Rock for practice.

The lifeboat shed was at the end of the causeway. They would fire a line to the ship, then secure the rope and bring the people to shore along it, in the breeches-buoy. The lifeboat was cork, with twelve oars. I remember the wreck of the Margot down on the Coorong in 1911. I remember the rocket being fired. There was Harry Battye, Joe Joy, the Williams and the Jarvis boys - all went out to her. They put the crew ashore to walk back along the beach, but it took three days for the lifeboat crew to get back, the wind kept blowing them away from the land, I remember Harry Battye said they thought they'd never see home again. Later two men died trying to salvage the cargo of wheat. It gave off poisonous fumes and they were overcome by it.

OLD FOLKS

The Lindsays owned all the land around where Lindsay Street is today. They gave land for the Church of England and the remaining blocks were sold off to working men.

Old Mrs. Lindsay used to go out in her hooded buggy with a big white dust coat on, like the men used to wear, and one of those pith helmets, like they wear in India. But on Sunday she would be nicely dressed in dark clothes to go to church, down here at St. Augustine's.

The Jarvis boys used to live near their gate, up in Crozier Road and would open it for Mrs. Lindsay and she'd give them sixpence. Later on, they had a contraption where she could drive over a bump in the road with the wheel and it made a chain pull the gate open. After she went through, she drove over another bump and it pulled the gate shut. They kept cows in the paddock.

THE WAR

When the war started old Tommy Nevin got up and told all the boys they should go. Some said they weren't going to go. I remember one of them saying he would rather be a coward than a dead hero. All those boys dying, I hope there'll never be another war.

There were a lot of “send-offs” and “welcome homes” during the war. They would have a concert with a dance to follow in the town hall. A lot of them didn't come home.

Claude Clark, the dentist's son went and Lance Cakebread and the Jarvis boys. They all came back except Keith Jarvis, the eldest (Keith Jarvis died and a tree is planted in his memory). He didn't come back and he was engaged to be married too. Of course there were those who said their boys weren't going to go. You can't blame people, when they have children and bring them up and then there's a war comes along, not wanting them to go. The boys weren't the same when they came back, there was always something. Jack Bruce was the first to be killed. He was a fine big handsome boy over six foot tall.

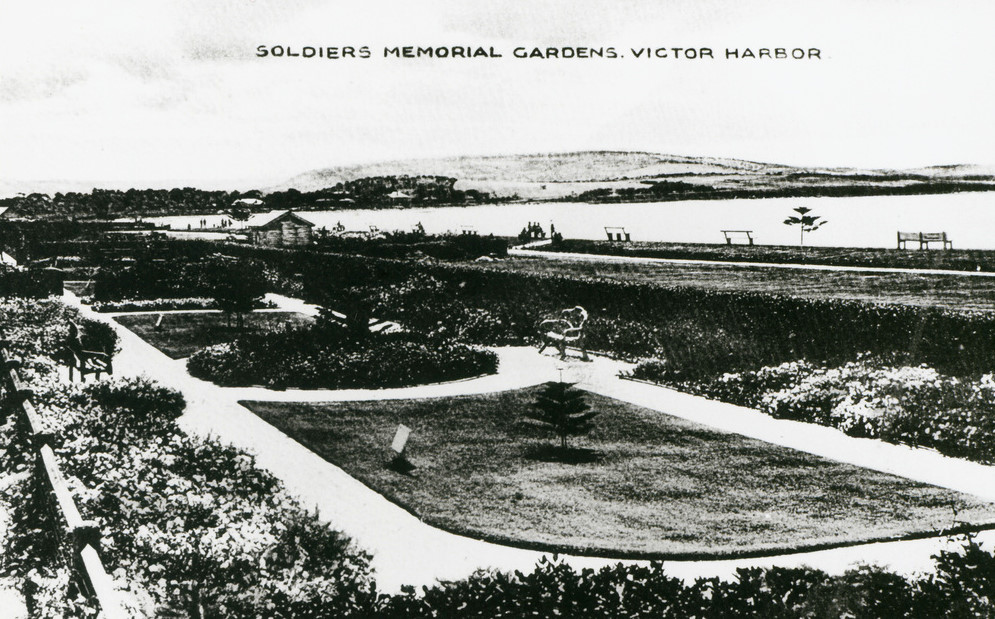

Before the Soldiers' Gardens were started by Bert Warland down on the sea front, they tried planting trees on the side of the Bluff. The trees never did very well there so they decided to put the gardens down on the seashore. They used to be beautiful once, full of flowers.

FIRE

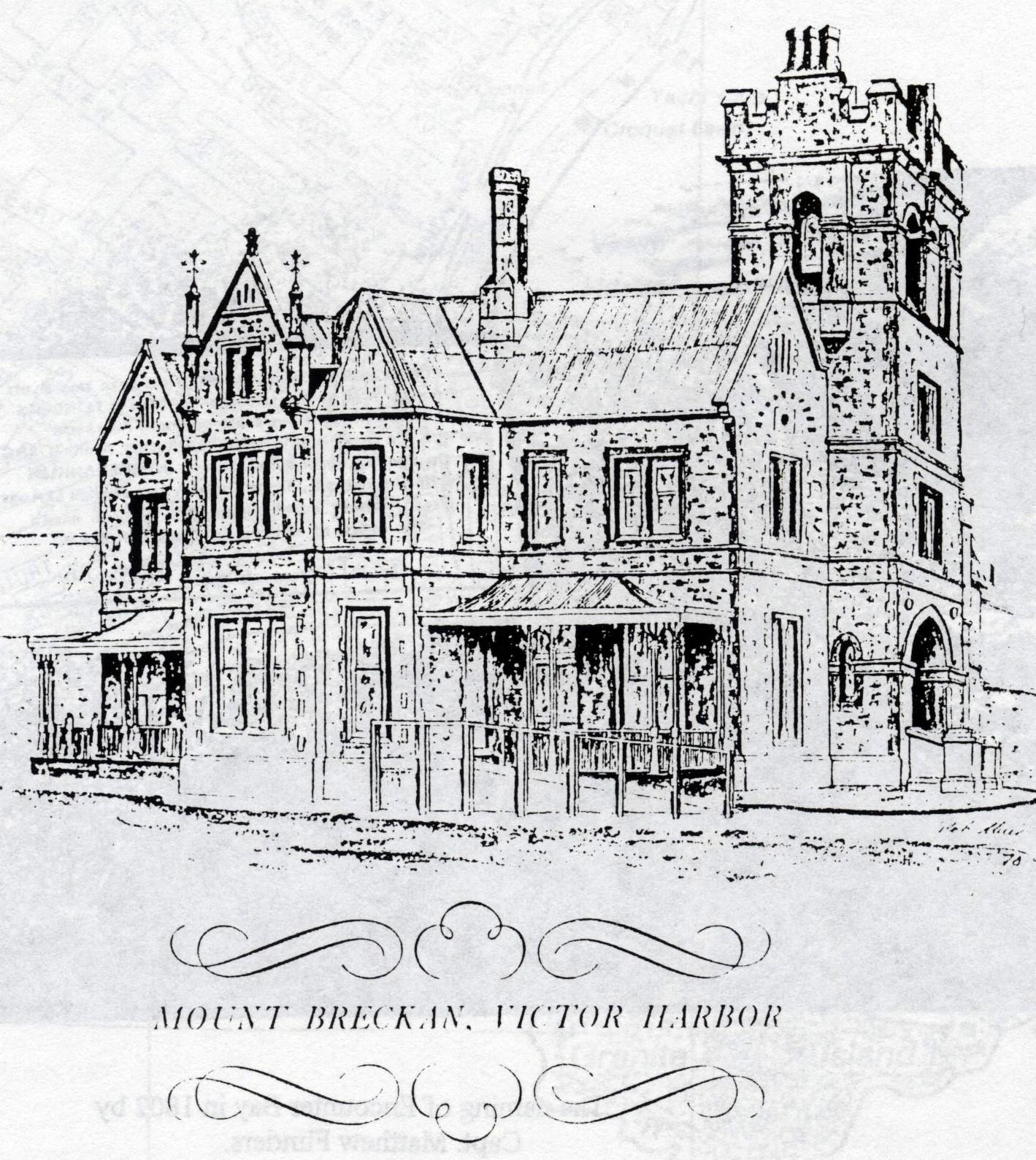

There was a fire at Mount Breckan. The children were at school and it was just after 2 o'clock - the train had just gone through - It was Feb 25, 1909. Folks in the town downed tools and went to help to fight the fire. The flames were lapping around the

windows and then crack the glass would fall in. The roof was slate with sheets of lead capping on the comers. As it got hot the lead melted, the slates slipped and you could see the roof beams all red hot and bit by bit they dropped down inside.

A plumber, down from Adelaide, had been working on a leaking tank in the ceiling that supplied water to the bathrooms. He took a lantern with a candle in it up into the roof , the kind that a door slides up. They should have had more sense and that is how it started.

The gardener was raking leaves when he saw a wisp of smoke coming from one of the vents in the gables. When he went to look the roof was full of flames. They saved most of the furniture from downstairs, It was all over in an hour but it kept smoldering all night.

The Hays went back to Adelaide, then a few months later Mrs. Hay and her daughter were lost at sea on the Waratah, on their way back to England. The Waratah disappeared on its' way to Cape Town and never heard of again.

Vandals smashed the eagles on the steps of Mount Breckan and wrote all over the walls. A couple of the gables fell in as well as the ornamental carving on the tower. It would have fallen down eventually if Mr. Connell had not bought it and had it rebuilt.

There was an old peacock left up there, strutting around amongst the ruins. You would often see him but couldn't get close before he flew off.

The old Post Offïce was in Coral Street. The first window (on the north end) was the

letter window, where you asked for your mail. The foundation is worn there from people resting their feet on it. A verandah ran right along. The old station master's cottage was in the alleyway behind the post office. They pulled it down in 1903 to extend the station. The original station building was weather board. It became full of white ants and dry rot. The turntable was where the railway station garden is now. It took two men to turn the turntable. Later it was moved up to Eyre Terrace. The Police Station was on the Crown Reserve (Warland Reserve). Walter worked as a station hand for a short while. His first job each morning was to sweep the office. He used to clip the tickets and sweep out the carriages when the 12 o'clock train came down. The porters came down with the train from the city and were supposed to help with the baggage. but they were down the road at the pub. He had to glue labels on the luggage with the old glue-pot. He didn't like working at the station so didn't stay long.

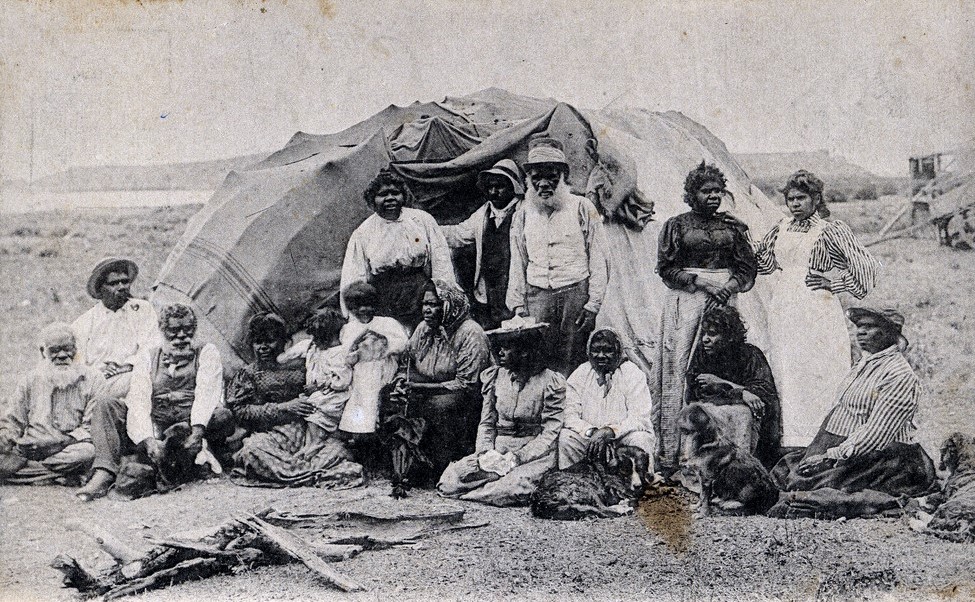

There are still a couple of trees near the road which were in the front garden of the police station. On the sea front were the wool stores. The Austral was the best hotel in town. All the toffs stayed there. The Aborigines were down in the Soldiers Gardens - they had their humpies there) They were often given the “left overs” from the dining room. There were other hotels - The Crown, Hotel Victor and many boarding or guest houses had opened up for people holidaying mainly from Adelaide.

Many of the affluent families had a house in the city and their “summer house” at Victor Harbor. This was so of the families who lived at Mount Breckan - the Hays - at Adair the Cudmores. These such places employed many of the local people.

EIGHT HOURS DAY

8 hours day was always a big thing at Victor Harbor in those days, There would be a

march with races afterwards on the reserve next to the old police station. The children

would race down to the cell walls and back again. The prize being a bag of lollies.

ABORIGINES

We'll never know how some of them lived, the old Aborigines. Some of our men used to chase after the women. They should have had more respect for their wives and left them alone. They used to camp in the sand hills, before that they camped where the Soldiers Gardens are. There were six to a dozen of them and their families in tents and humpies. Then they moved to the point at the mouth of the Inman River The government put three weather board houses on the Inman banks for them. They held Corroborees on the Crown Reserve in the early 1900's, dancing and clapping their hands and singing.

Poor old things they paddled about in their bare feet summer and winter, no wonder so many of them died. Some of them contracted tuberculosis. Each week they went down to the police station to collect their rations from the government. People were kind to them, giving them cups of tea and something to eat.

One lady working in her front garden - behind a hedge - heard one of them say “We'll go in here but we probably won't get much, they're mean buggers”. Sometimes you'd see the men in the sand hills, they'd get a bottle or a white man would buy them one. They were not allowed to have alcohol in those days.

They were hard workers and worked for the Corporation around the town. Some were

employed by the larger households whilst many taught the local children to swim. They collected rushes from Goolwa and made beautiful round rush mats and baskets with lids.

They went to school with the local children and were good scholars. The boys were good footballers and cricketers. Many children were educated at Point MacLeay Mission.

Harry Butler flew his plane and landed at Mount Breckan on the golf course by the river. That was New Year's Day 1920.

In 1921 someone landed a plane on Granite Island. The pilot gave rides for 10/- as a fund raiser.

The Depression saw hard times with so many people out of work. If you didn't work you starved - it is all so different now.

During World War II the RAAF took over Mount Breckan. The foot bridge was opened on the Inman River in 1937.

The Bruces' houses in Burke Street were demolished in 1990 as they were badly in need of repair. Two stately homes were built for wealthy families from Adelaide and are still there today.

Mount Breckan was built by a canny Scot, Alexander Hay who emigrated to South Australia in 1839. He was successful in business and in land dealings. He became the Honourable Hay after gaining a seat in the first House of Assembly of S.A. in 1857.

They had a magnificent home in Linden Park, Adelaide. His second wife suggested that they build a small seaside cottage on the hill at Victor Harbor. In 1880 making a grand gesture he erected Mount Breckan, a stately mansion of twenty-two rooms with an eighty-foot tower. It was designed by a Scottish architect, cost 10,000 pounds to build, and was set in a well-wooded estate overlooking the harbour and the Hindmarsh River.

After the house was completely burnt out by fire in 1909, Mrs Hay and her daughter boarded the “Waratah” for a holiday in Europe. All went well until they left Durban after which they were never heard of again. It was presumed that she was top heavy and turned over.

Mount Breckan was rebuilt as an exclusive guest house with a nine hole golf course. Much of the land was sold off in large parcels and homes with breath-taking views were built.

In the Second World War Mount Breckan was acquired by the R. A. A.F. for the training of air crews, and afterwards it was used as a Rehabilitation Centre. In 1960 the building was purchased by the Adelaide Bible Institute. Today over 100 theological students from all States and overseas prepare for diplomas and degrees in divinity at Mount Breckan.

Adair looked like a fairy castle The house was built by the Cudmores. They owned “Avoca Station” and a house in the city. Adair was their summer house. They had gaslights that could be raised or lowered by weights, before that they had kerosene lamps on stands. The spires on the turrets were eight feet tall.